One’s fate is linked with the date of their birth, according to an ancient astrological calendar created by the Indigenous Maya people that is still followed by some communities. This calendar enabled the Maya to predict eclipses for nearly a millennium, according to new research, illuminating a mystery that has long puzzled scientists.

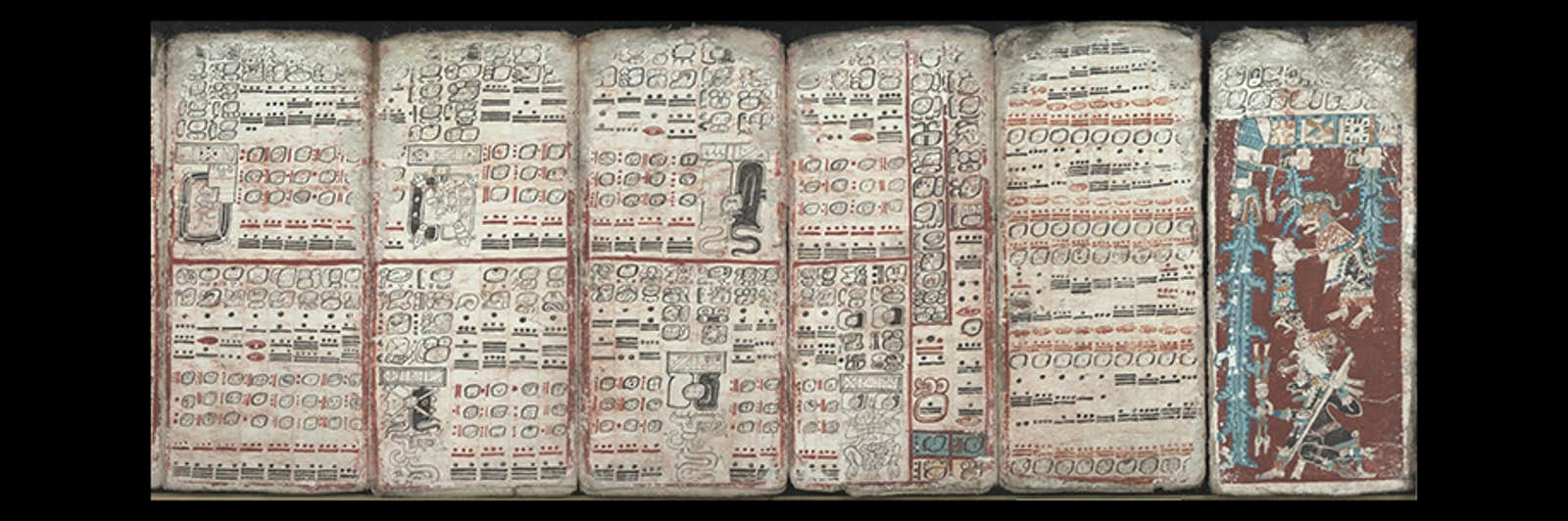

Researchers took a close look at the Dresden Codex, a Maya bark paper book dating back to the 11th or 12th century—among the oldest surviving books from the Americas—for clues. It included a table detailing 405 lunar months, which scientists previously thought was solely for eclipse prediction. But the exact workings behind the table have remained murky.

Now, researchers from the University at Albany and SUNY Plattsburgh suggest that this table emerged from a lunar calendar that corresponded with the Maya’s 260-day astrological calendar, according to a paper published in the journal Science Advances. After crunching the numbers, the researchers demonstrated that the table’s 405-month cycle—containing 11,960 days—corresponds with 46 cycles of the 260-day calendar, allowing the Maya people to follow when rituals coincided with eclipses.

By around 500 BC, Maya calendar specialists known as daykeepers connected their ritual calendar with their observations of the moon. Then, around 453 AD, they may have experienced enough passes through the 405-month cycle to glean the patterns behind solar and lunar eclipses.

But how were the Maya eclipse predictions so spot-on? To get things right for 700 years, authors John Justeson and Justin Lowry note, the Maya relied on overlapping tables. Once they reached the end of a cycle, instead of simply starting a new one, they reset the count at precise intervals—223 and 358 lunar months before the conclusion of the previous table.

The researchers compared the Maya lunar table with natural eclipse cycles, which are associated with the time it takes for the Earth, sun, and moon to dance into a nearly straight line. They found that resetting their table at such intervals allowed the Maya to accurately predict every eclipse that occurred between the years 350 and 1150 AD because the method was able to “correct for small astronomical errors that accumulate over time,” according to a statement.

This spirituality-infused technique might still hold strong, according to the paper, and the calendar system could be maintained to work “indefinitely.” ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: Linear77 / Wikimedia Commons.