Oct. 14, 1943, was the date of one of the more successful Allied air raids on German factories during World War II. The United States Army Air Forces targeted ball-bearing factories in Schweinfurt in an attempt to disrupt the Nazi war effort. The raid, on what is now known as “Black Thursday,” achieved its goals, but at a great cost. Of the 291 B-17 bombers taking off from Britain, 77 were destroyed and only 33 returned undamaged. More than 600 of the 2,900 soldiers involved in the mission were killed or captured.

The B-17 was the most heavily used bomber in the U.S. war effort in Europe, dropping more ordnance than any other plane, but the losses were staggering. Fortunately, the damaged planes that returned provided a rich set of data for the air forces to study in the hopes of increasing survival rates. Reinforcing the entire plane against anti-aircraft fire would be infeasible—the added weight would reduce the range and cargo capacity too much. But perhaps parts of the planes could be reinforced. If the damage to the planes was random, there would be little benefit. But if the damage was systematic, affecting some parts more than others, then the army could fix the vulnerable sections, strengthen the planes, and possibly end the war sooner.

We tend to devote more attention to cases that are still around, neglecting those that are not.

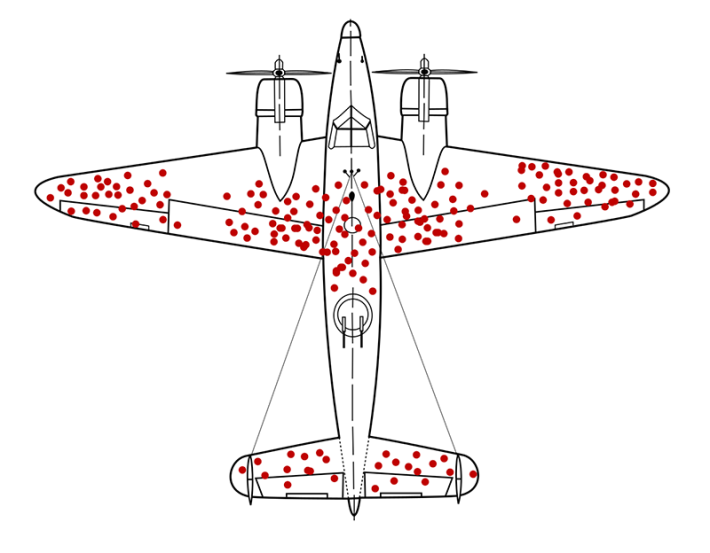

To help with this problem, the army found Abraham Wald, a Romanian-born statistician working with the Statistical Research Group at Columbia University. Wald’s work remains influential, with some of the statistical techniques he developed commonly used in psychology, economics, and other disciplines today. At the time, he was developing methods in the field of “survival analysis,” and he conducted a systematic study of the damage to B-17 planes. If the damage was entirely random, the odds that a part of the plane would be damaged should scale with the size of that part; bigger parts should be hit more often than smaller parts. The pattern Wald found was likely encouraging to the army: Some parts of the plane were disproportionately more likely to be hit than would be expected by chance.

Now, imagine that you are in charge of B-17 safety. How would you use Wald’s results? The most obvious plan would be to bolster the surfaces that take a disproportionate amount of damage—for example, adding steel plating wherever the planes are most often hit.

If that was your conclusion, congratulations! You made a possibly disastrous—if common—choice. Why? All you need to do is think about the evidence that is missing. Wald’s analyses of damage were based on the planes that managed to return. The areas more likely to have been damaged on the planes that returned were in fact less likely to be critical to a plane’s survival. What was missing is what happened to the planes that did not return. Presumably, if those undamaged areas were unimportant, you would see damage to them on the planes that returned. And if those areas were crucial to a plane’s survival, planes hit in those areas would be less likely to survive. In other words, the planes that went down were perhaps damaged precisely in those parts that remained intact on the surviving planes.

Wald understood this, of course. His analysis of the B-17s helped lay the groundwork for the concept now known as survivorship bias. We tend to devote more attention to cases that are still around, neglecting those that are not. That bias leads to a systematic misunderstanding of success and failure that plagues many consequential decisions. It helps explain why studying an investor who made a few great stock picks can’t tell you your own odds of beating the market, why adopting Amazon or Google’s business practices won’t necessarily make your own startup a winner, and why so many books on leadership won’t help you become a leader.

If you understand how survivorship bias confuses us about cause and effect, you should be able to see the logical flaw in this statement about coronavirus vaccination by the podcaster Dave Rubin: “I know a lot of people who regret getting the vaccine. Don’t know anyone who regrets not getting it.”

Remember the bullet-ridden airplane meme whenever you hear someone discuss what they concluded from the information they have. It should cue you to wonder about the information they are missing, because what’s present may not be representative of what’s absent. ![]()

Excerpted from Nobody’s Fool: Why We Get Taken in and What We Can Do About It by Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris. Copyright © 2023. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Lead image: Kyle Cr8on / Shutterstock