Paula Watnick and Roberto Kolter were the first to compare biofilms to cities. I found this metaphor—from their 2000 paper, “Biofilm, City of Microbes”—to be a perfect description of what one would see at the microscale when descending into the microbial world.

Biofilms are intricate communities of microorganisms that form on various surfaces, from rocks to medical devices. If you pay attention, you can find biofilms everywhere. Much like our human cities, biofilms in nature are complex, highly differentiated, and multicultural. Multiple different species of bacteria fill distinct niches in the microbial community and stay and leave in strategic and deliberate ways.

In human cities, “chefs and grocers may settle together in the restaurant district, while musicians may settle near concert halls,” write Watnick and Kolter. The same is true for biofilms. Bacteria select their place in the biofilm based on which microenvironments suit them best and which neighboring bacteria offer the most rewarding symbiotic relationships.

When humans settle in a city, they first select a neighborhood, then choose a home that suits their needs, and, ideally, form cooperative relationships with their new neighbors. When a bacterium joins a biofilm, it follows a similar pattern. First, the bacterium approaches a natural surface, such as a rock, then it forms “a transient association” with the surface or with other microbes previously attached to the surface, or both—the neighborhood. This perch allows the bacterium to search for a perfect place to settle down.

When the bacterium joins a microcolony, its attachment becomes longer lasting—it has chosen its new home. But if environmental conditions become unfavorable, the biofilm-associated bacterium may detach and swim away to find new living quarters. Some bacteria stay put, while others migrate—much like a bustling city. As the biofilm matures, it grows into a complex three-dimensional structure—with skyscraper-like structures.

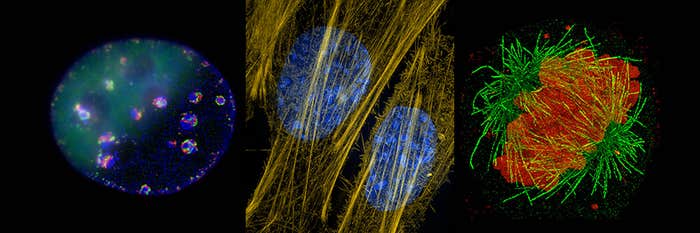

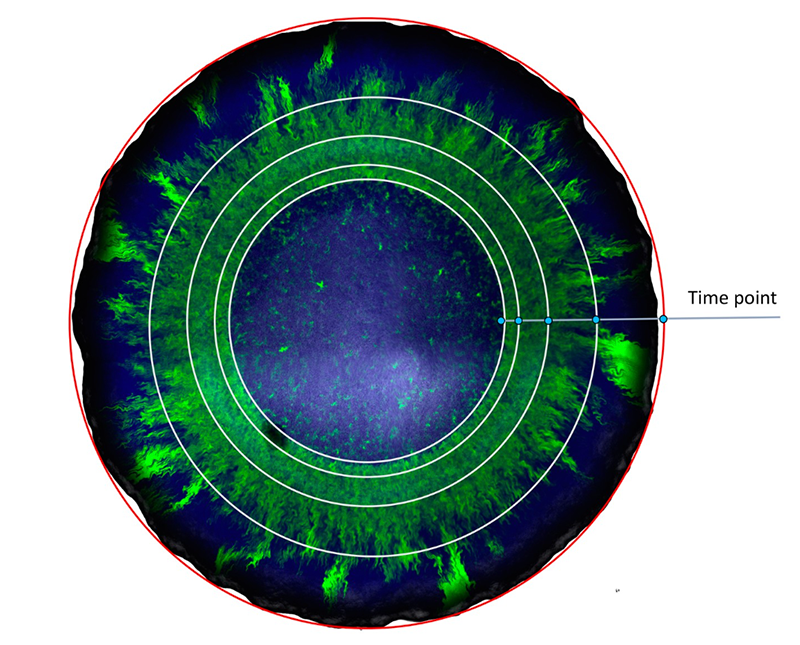

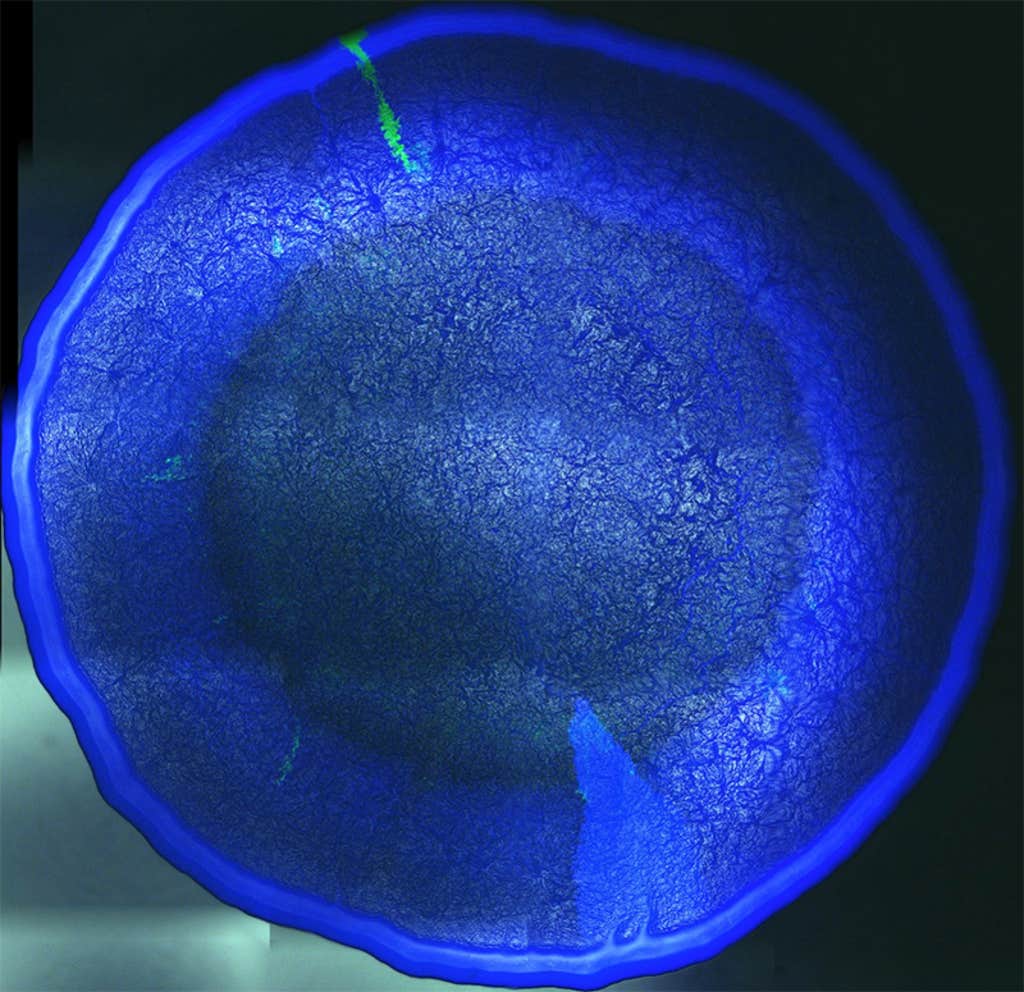

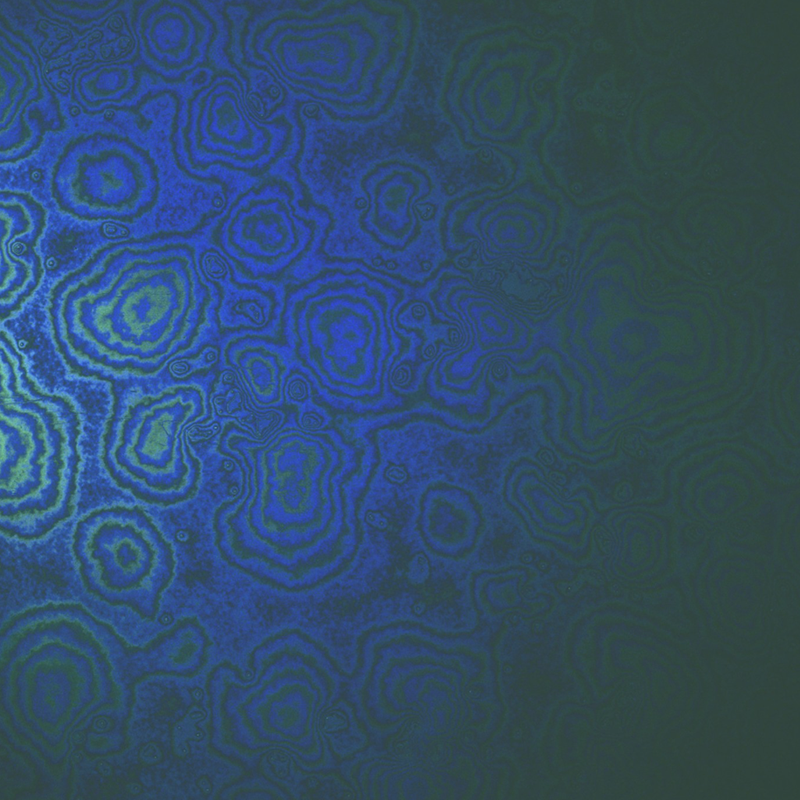

I took these photographs of biofilms through a microscope during my study of the microbiome. The bacteria were modified to carry either green or blue fluorescent protein, which allow us to track different bacterial species and study their patterns at the colony level. ![]()

Adapted with permission from David Ciccarese’s Instagram account, @microscaleworld.

Lead image: Tasnuva Elahi; with images by Sensvector and Kudryashka / Shutterstock