I have been wanting to do this since I was 5 years old,” Apple CEO Tim Cook proclaimed to a packed San Francisco auditorium on March 9, 2015. “The day is finally here.”

The standing ovation that Cook received as he announced the arrival of the Apple Watch, and revealed that he could make phone calls through a miniature microphone and speaker, showed that many techies shared his childhood fantasy. Lest anyone fail to recognize the origin of this collective dream, media outlets far and wide touted the product launch as the long-awaited debut of the two-way wrist radio, famously worn by Dick Tracy, the most celebrated comic strip detective of the 20th century.

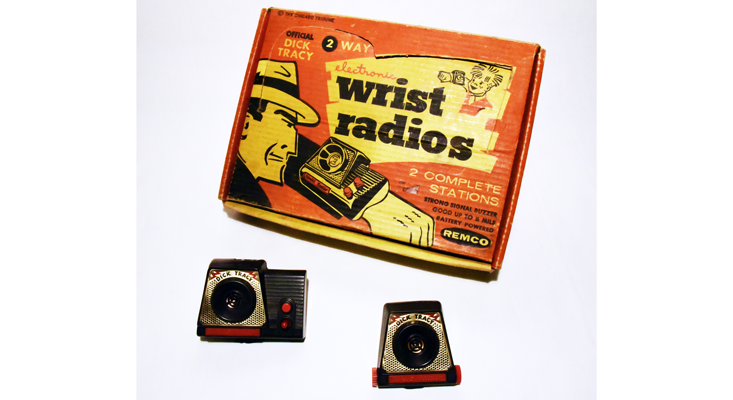

In truth the wrist radio had been available since 1947, just one year after the cartoonist Chester Gould outfitted his undercover cop with the iconic gadget. In a comic book advertisement, a New York electronics manufacturer called Da-Myco offered “the most amazing invention you’ve ever seen” for $3.98 postpaid. Although the Da-Myco product lacked the fictional gizmo’s 500-mile range—and the diminutive crystal radio had to be hardwired to other units in order to communicate with them directly—it was “not just a dream … but a scientific reality”: an early-stage communications technology that allowed children to play out the future foretold in the comics.

The Dick Tracy two-way wrist radio is one of countless toys from the 20th century that prophesied the world in which we live today. Although many of these futuristic playthings anticipated technological innovations and societal changes that have not yet come to pass—and might never arrive, especially if laws of nature stand in the way—each product has given older generations significant influence over younger ones by setting expectations.

Futuristic visions have a powerful effect on children’s imaginations. Futurists often say that these visions “colonize the future,” analogous to the colonization of continents belonging to other peoples. But unlike encroachments on indigenous territory and native autonomy, which are never defensible, premonition can potentially be a gift, nurturing new ideas and helping to set priorities in advance.

Instead of showing kids what the future will bring, toys need to ask what kind of future they want.

Back in 1991, when Apple was still just a desktop computer manufacturer, University of Arizona archaeologist Michael Brian Schiffer wrote a book titled The Portable Radio in American Life, in which he coined the term cultural imperative to describe “a product believed by its constituency to be desirable and inevitable, merely awaiting technical means for its realization.” The examples he cited included the television—which had entered the consumer marketplace largely because RCA president David Sarnoff was convinced of its desirability and inevitability—and Dick Tracy’s signature communications device. “The Dick Tracy radio and other radio toys introduced young Americans to the expectation that radios would become ever more portable,” Schiffer argued in his book, a claim he might have made about phones a decade-and-a-half later. The cultural imperative, with its cultish tone, could hardly have found more vivid expression than the standing ovation Cook received in 2015.

Chester Gould’s wrist radio communicated its imperative all too clearly. The question for visionary artists, innovative toy makers, and responsible parents is how to avoid cultural imperatives that colonize the future. Instead of purporting to show kids what the future will bring, futuristic toys need to ask children what kind of future they want.

At the end of the 19th century, a British clerk named Frank Hornby invented a new way to keep his boys entertained. Observing how cranes on the Liverpool loading docks were made with interchangeable parts, he designed a set of miniature girders and wheels that could be fit together in myriad configurations to make numerous machines and structures, from tractors to towers. Initially called Mechanics Made Easy and later shortened to Meccano, his kit was the first industrial construction set for kids.

Meccano rapidly became an industry unto itself. Offering numbered construction outfits, each sequentially larger yet all designed to fit together, and a series of instruction books showing ever more advanced projects, Hornby successfully created a proprietary system through which children literally and figuratively engaged the engine of capitalism.

The purpose of Meccano was unabashedly didactic, a position reflected even in Hornby’s 1901 patent for “improvements in toy or educational devices.” In marketing materials, the product was presented as a sort of apprenticeship-in-a-box, teaching “correct” engineering principles that competing toys purportedly failed to demonstrate. Or as Hornby phrased it himself in an early biography written for his core audience of boys, “you are building for the future.”

This message was paradoxically reinforced by Hornby’s own identification with the past—he immodestly compared himself to James Watt—and by his efforts to anchor Meccano in the present. Meccano magazine, a periodical that published Meccano instructions and advice for “Meccano boys,” regularly featured technical devices made by grown-ups with Meccano components. Ranging from microtomes for microscopy to differential analyzers for ballistics calculations, these mechanisms took advantage of the convenience and versatility of metal parts pre-cut in standard sizes. One implicit lesson was that everything could be made in this way. Another was that this way of making things was inevitable in the future because it was already happening and had been since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. As with the Da-Myco wrist radio—and later versions of the Dick Tracy toy made by Remco and the American Doll & Toy Corp.—the “scientific reality” enhanced the technophilic promise of a world in which man could do anything with enough mass-produced girders and bolts.

Taking away mass-produced toys outright might be one way to achieve that goal.

The impact of this promise can be seen in the world today, as can the limitations of Hornby’s industrial-strength vision. Prominent architects including Norman Foster, who designed the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank Building, claim to have been inspired by Meccano. The architect Richard Rogers has even more directly engaged Hornby’s invention by making models for buildings out of Meccano parts. And he and Renzo Piano described their most famous building, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, as “a giant Meccano set” in a statement they published in Architectural Design in 1977, the year that construction was completed.

On a superficial level, the comparison is apt. But the colorful struts that gave the Pompidou its distinctive Meccano look had to be custom made to the architects’ specifications at extraordinary cost. Even the modularity of the building touted by Rogers and Piano—which they contrasted with the “static” quality of traditional architecture—has proven to be more hype than reality. As Oxford Brookes University architectural theorist Francesco Proto has noted in The Journal of Architecture, “the ideological perception of the building exceeded the real possibilities suggested by its hyper-flexibility.”

The engineering principles taught by Meccano may have been technically correct, but they were not always applicable to the realities of modern industry. Nor were they always amenable to maintenance of a shiny new museum in a dirty old city. On the most banal level, the placement of heating and ventilation ducts on the exterior of the building has created a needless impediment to washing the windows.

By engineering standards, the Pompidou is far less practical than many buildings that make no allusion to Meccano. Engineering problems are not all interchangeable. A system of interchangeable parts is not universal. Good engineering depends not only on what is possible but also on what is appropriate.

Ironically Meccano limited the imagination of children who played with it because it gave the illusion of being unlimited. Hornby excluded all non-industrial answers to the question of how to build for the future, an omission that has become more obviously problematic as we have witnessed the ecological devastation wrought by industry. If the Dick Tracy wrist radio introduced a cultural imperative, Meccano presented an operational mandate. The future can be occupied by what children want to have and also what they expect to achieve.

In 2002, the sociocultural anthropologist Jean-Pierre Rossie traveled to the Anti-Atlas Mountains in Southwestern Morocco to study children’s play habits. A local schoolteacher he met gave him some toys made by students several years earlier, including a cellphone crafted in clay by an Amazigh child who was 6 or 7 years old at the time of fabrication. Over nearly a decade, Rossie accumulated more examples, made by both boys and girls. He also collected toy televisions and cameras made out of scrap materials. These were similar in their style of craftsmanship to much older toys from Morocco, and also consistent with the older toys’ imitation of real objects, but they differed in one important respect. “[T]he inspiration for [children’s] pretend play comes today more than in the past from situations and information that are not solely related to local life, but seep into the child’s world through television and tourism,” Rossie observes in Technical Activities in Play, Games and Toys.

What is found in Morocco has parallels throughout Africa. Handmade toy cellphones and electronics are seen in Mozambican villages and Ugandan refugee camps. They are artifacts of globalization, reflecting media saturation and cultural homogenization. However they can equally be interpreted as bottom-up expressions of children’s wishes. In other words, African children’s futures may be colonized by TV networks and tourists, and the urge to catch up with the “developed” world, but these boys and girls are exploring the developments they anticipate and want with their own hands. Their self-directed inventiveness with mud and recycled materials makes their perceptions of the future malleable. Their surroundings are their Meccano.

In fact, Meccano and other building kits could benefit from observation of these children’s play habits. Instead of developing closed systems with ever more pieces—the Hornby model, subsequently mastered by Lego—they could approximate true universality by opening up to the whole universe.

A first approximation of that alternate reality—one in which the benefits to children override corporate profit margins—was created in 2012 by the artists Golan Levin and Shawn Simms. Their Free Universal Construction Kit is a set of 80 blocks that allow children to connect parts from 10 popular construction sets including Lego and Tinker Toys. The blocks are freely distributed as digital files that anyone can output on a Makerbot. Of course the Free Universal Construction Kit is totally unauthorized. As Levin noted in an audio tour for a 2015 Museum of Modern Art exhibition where the blocks were exhibited, “the kit is not a product, but rather it’s a provocation.”

What if kids were invited to play-test emerging technologies, initially introduced as toys?

Why not take the provocation to the next level? To rupture the internal logic of these toys, and to deflate the operational mandate of industrialization, requires more than just offering interoperability. For children to build their way toward all possible futures, they need to be able to choose the building paradigm.

Taking away mass-produced toys outright might be one way to achieve that goal. The creativity of children in Moroccan mountain villages and Ugandan refugee camps is induced by the paucity of consumer goods (as becomes evident with their abandonment of mud and found materials whenever consumer goods become available). But it’s hard to imagine much popular support for a Luddite Ebenezer Scrooge. And in any case, toys have the capacity to inspire children, not only to confine them.

The ideal Meccano set would actively challenge children to prototype possible futures beyond anything they’ve seen or their parents could imagine. A hybrid building paradigm could inspire genuinely novel experimentation by children. Imagine a kit that combined the logic of how industrialists build with the way nature does. Imagine the models that could be built, where portions would be bound together with bolts and parts would be grown from seeds.

If Chester Gould was a Meccano boy, history does not record it. He certainly never tinkered with wrist radios himself. The idea for Dick Tracy’s favorite gadget originated when Gould visited the inventor Al Gross in the winter of 1945.

Gross had recently played a pivotal role in World War II, inventing the first battery-operated ground-to-air radio, which the Joint Chiefs of Staff would later credit with “saving millions of lives by shortening the war.” But he was more well known at the time for having invented the walkie-talkie, which had originated with his teenage fantasy of operating a HAM radio on the go. He patented his walkie-talkie in 1938, at the age of 20, and was tinkering with a wrist-size version when Gould came calling.

Gross wasn’t a man to follow a cultural imperative. His name does not appear in Schiffer’s book, and there is no historical evidence to suggest that he was trying to fulfill the vision of a pocket radio that Schiffer meticulously traces back to the publisher Hugo Gernsback in the first decade of the 20th century. Instead Gross innovated in a playfully open-ended way. He patented a pager, an automatic garage door opener, and a cordless phone, none of which found a market in his time. “If I still had the patents on my inventions, Bill Gates would have to stand aside for me,” he quipped to the Arizona Republic near the end of his life. Gross’s inventions have less in common with products than with philosophical instruments, each begging the question what if?

The answers were often telling. When Gross brought his newly invented pager to a Philadelphia medical convention in 1949, doctors responded in horror that it would interrupt Sunday golf games. What might have seemed laughably shortsighted at the time was actually prescient. Provoked by the prospect of beepers on their belts, the doctors anticipated the downside of 24/7 availability—and divined the Pyrrhic victory achieved by Apple with the apotheosis of the smart watch.

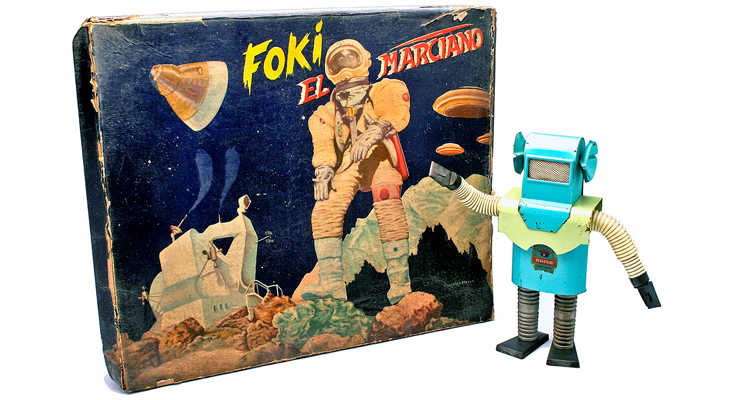

What if futuristic toys were to ask what if? What if they were presented as possibilities instead of selling themselves as desirable or inevitable? What if the possible futures they represented were multiple and divergent? This has happened inadvertently in the case of toys that have been constrained by manufacturing limitations. In the late 1960s, an Argentine home appliance manufacturer called Daisa made a toy robot called Foki that was supposed to be an artificially intelligent android of extraterrestrial origin but bore closer resemblance to a reconfigured vacuum cleaner. Foki presented children with a sort of cognitive dissonance that arguably opened their minds to asking what sort of relationship they wanted to have with future technology.

But what if the cognitive dissonance were deliberate? Or what if children were invited to play-test emerging technologies, initially introduced as toys, instead of being handed their parents’ cultural imperatives?

Playthings don’t have to play that old game. Toying with tomorrow, children can co-invent the future in the here and now.

Jonathon Keats, founding director of the Museum of Future History, is an experimental philosopher, artist, and writer. He is the author of six books, most recently You Belong to the Universe: Buckminster Fuller and the Future. This essay is adapted from Toying with Tomorrow: Playthings That Anticipated the Here and Now, the first publication of the Museum of Future History, published in association with the UNESCO Futures Literacy program.

Lead image: freedomnaruk / Shutterstock