Though they were only written down in the 13th and 14th Centuries, much of the Icelandic Sagas read like histories of Viking settlements in Iceland several hundred years before, including realistic-sounding journeys of exploration and discovery. Some of them seem rather less plausible; see the Saga of Erik the Red, where Erik’s son is shot in the stomach by a one-legged man-creature on the shores of North America who escapes by hopping up a stream. A great deal of scholarship is devoted to the not-insignificant task of determining to what extent the events really happened. Now a new statistical study concludes that the social networks described in the sagas at least are realistic, sharing many qualities with ones in the real, modern world.

The sagas lend themselves well to this kind of analysis—they read a little like the newspaper of a very eventful village, or maybe a deranged family scrapbook. They tell of the activities of well over a thousand folks, many of them relations, who are in varying degrees of warfare with each other and are constantly undertaking strange and bloody journeys overseas. And you rarely hear about these people just once. Individuals who have starring roles in one saga crop up elsewhere as bit characters, like cousins in the background of a group photo. It’s one of the sagas’ more charming features.

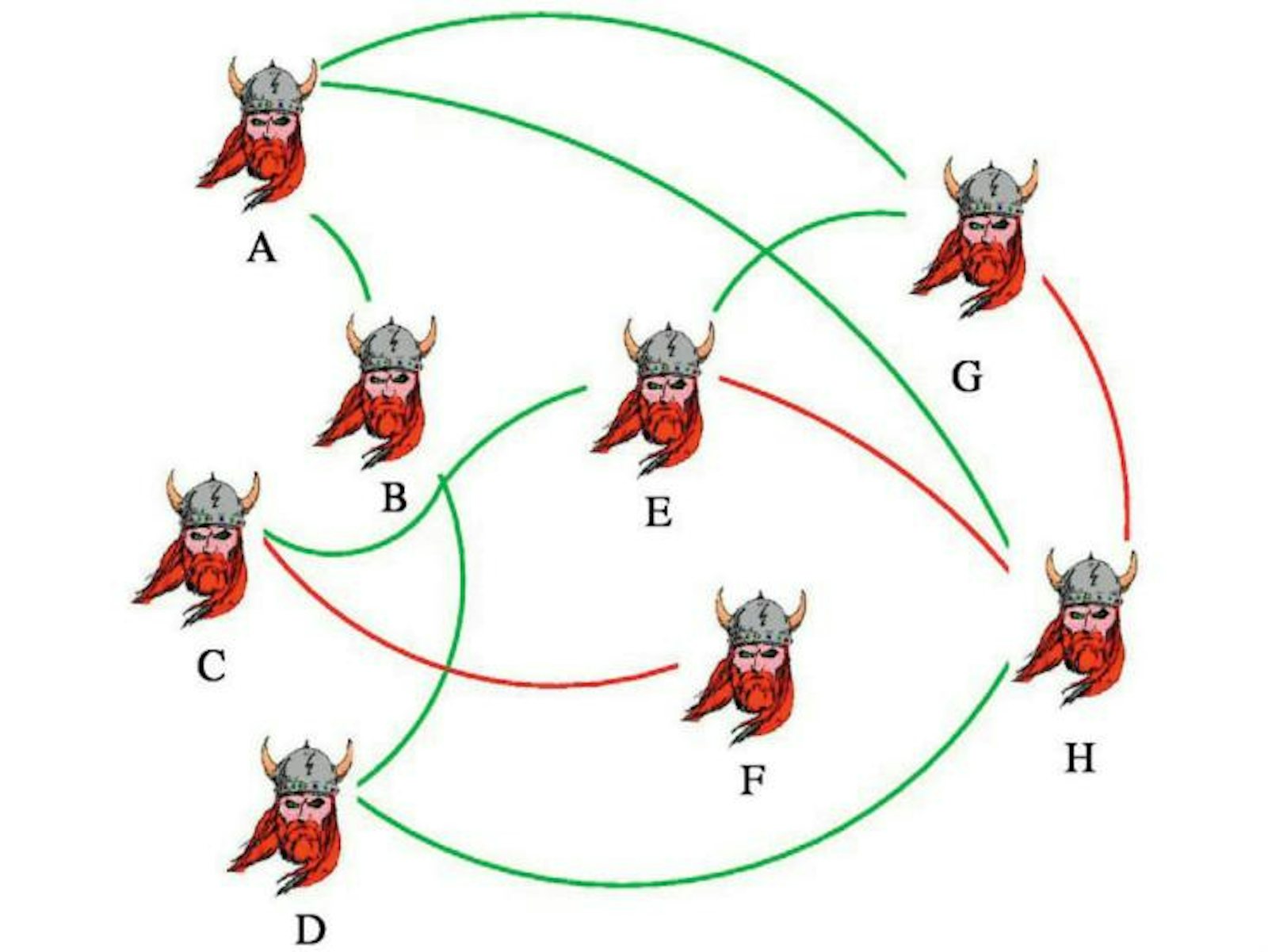

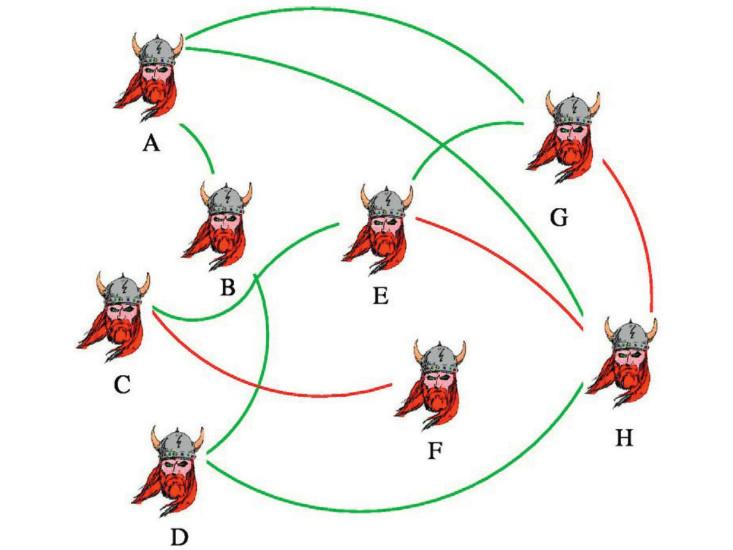

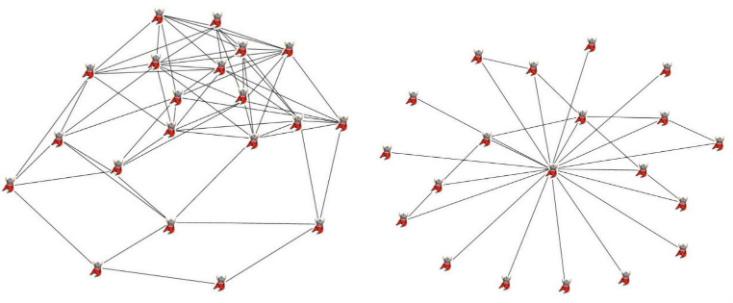

The researchers, who are based at Coventry University in the UK, looked at the connections between characters in 18 sagas, a total of over 1,500 people. They calculated certain characteristics about the networks within five of the most populous sagas and throughout the group of sagas as a whole. The social networks tend to be what network scientists call “small world,” the researchers found—the number of hops between any two given people on the network isn’t large, and if one person knows two other people, those two people are very likely to know each other as well. Modern social networks also tend to be small worlds, and, like most of the saga networks, they also are assortative, meaning that people who are connected to each other tend to have a similar number of connections.

Small worlds with these particular characteristics aren’t uncommon, but it’s interesting that the saga networks should line up along the same lines as modern ones. Additionally, the sagas’ networks are different from those in explicitly fictional works, the researchers say. Last year, as part of an ongoing project to study epic and mythological literature, they analyzed Beowulf, the Iliad, and the Irish Táin Bó Cuailnge this way. They find that the first two, which are thought to be embellished versions of real events, have social networks that are more similar to real ones. The Tain, which is regarded as primarily fictional, has a network that’s closer to those in the Marvel superhero comics—mostly because there are certain characters who are absurdly well-connected, who know everyone.

The findings suggest that the sagas might have been based on reality, at least in the matter of the human relationships described. But one-legged hopping men remain, shall we say, unsupported.

Veronique Greenwood is a former staff writer at DISCOVER magazine. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Popular Science, and the sites of Time, The Atlantic, and The New Yorker. Follow her on Twitter here.