One question for Jonathan Balcombe, a biologist who studies animal behavior, and the author of four popular science books on the inner lives of animals, including Pleasurable Kingdom, Second Nature, and What a Fish Knows, a New York Times bestseller.

What does a fish know?

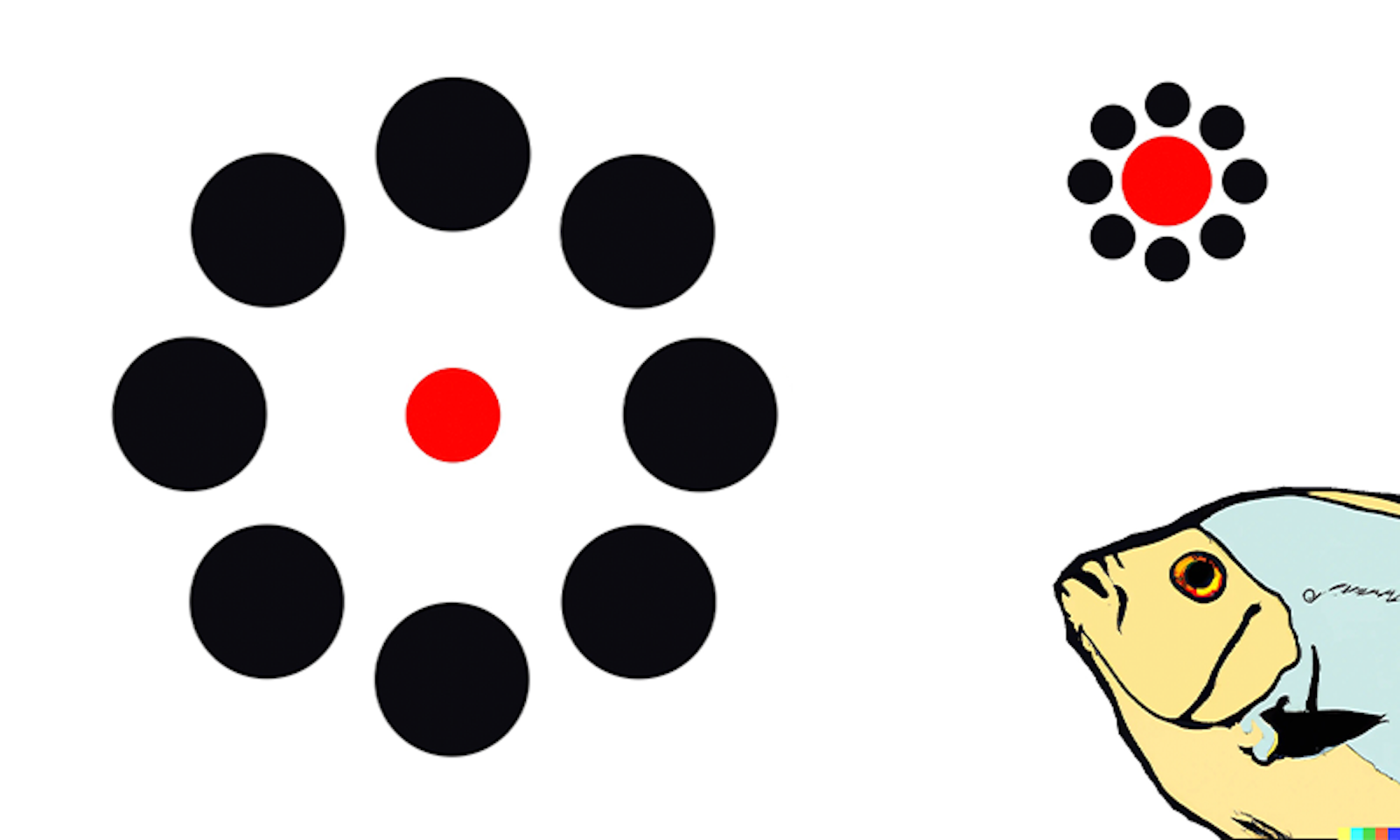

Fish have great memories. They have great individual recognition skills. They have soulmates, individuals who they consort with and know and presume to care about. They show artistic creativity in nest building. They show culture. They fall for the same optical illusions we fall for. You can train a fish, for instance, to poke their nose against the larger of two circles when they’re presented with two circles. I give them a little food reward for that and then present them with the Ebbinghaus illusion, which is two identical circles with dots around them with different sizes. It’s a strong optical illusion in which one of those identical circles looks bigger than the other, and these fishes of various species have been tested in this and other optical illusions.

When presented with the Ebbinghaus illusion, they’ll go to the circle that looks larger and poke their nose or push the button, whatever the routine is to indicate that that’s the one they think is larger. That’s telling. It tells you that the fish can have beliefs, and those beliefs can be wrong. Nature’s full of deception and that’s one way that deception works, because you can fool one another.

Fish have beliefs. They have inner lives. They’re individuals with personalities.

There’s another mind-blowing study where fishes were subjected to stressful procedures. They were caught and put in a bucket of shallow water for 30 minutes. Very stressed. How do you measure that? You take a small blood sample from the tail vein and you can measure very high cortisol, a stress hormone, the same one we have. And then these animals were given an opportunity to get caresses, to get stroked from a model of a fish. The stressed surgeon fishes, when they had the opportunity to get strokes, would swim up to that model and get strokes an average of 15 times an hour. Fishes in the control group had a model fish that couldn’t give them strokes; it just was stationary. They didn’t visit it at all. They didn’t have any reason to go there, because it couldn’t deliver caresses that would cause them stress relief. The individuals in the first getting the strokes had their stress hormones come down rapidly and profoundly.

That I think says so much more about fishes than we routinely credit them with. They have inner lives. They’re individuals with personalities. I like to say they don’t just have biology—they have biographies. And we tend to view them and treat them as we see them in the market. Just rows of anonymous similar-looking individuals. It’s a salmon instead of that particular individual who had a unique life. ![]()