On April 27, 2011 a monstrous EF5 tornado traveled 132 miles across northern Alabama and into southern Tennessee, missing one of the nation’s largest nuclear power plants by less than two miles, and also skirting the grounds of an Alabama state prison and obliterating the Alabama towns of Hackleburg and Phil Campbell. In Hackleburg, the tornado destroyed 75 percent of the structures, killed 18 people and crumpled a Wrangler blue jeans plant.

The jeans were syphoned up into the air, and somewhere in the anvil of the thunderstorm that had spawned the twister they joined high school letter jackets, family photographs, homemade quilts, metal signs, and all manner of documents. In the lingo of meteorologists this horrific aerial parade of items, snatched crudely from the human world below, is known as tornado debris.

“What I find most amazing,” said University of Georgia atmospheric scientist John Knox, “is how The Wizard of Oz is truer than anyone might think with regard to tornado debris. Admittedly, the stuff in the storm is mangled pieces of houses and their contents, instead of Dorothy and Toto in an intact house, but the idea that objects from the surface can go very high into the storm is accurate.”

First, an object is blown horizontally out of a structure, then drawn vertically into the air along the outer wall of the tornado, possibly spiraling around its core.

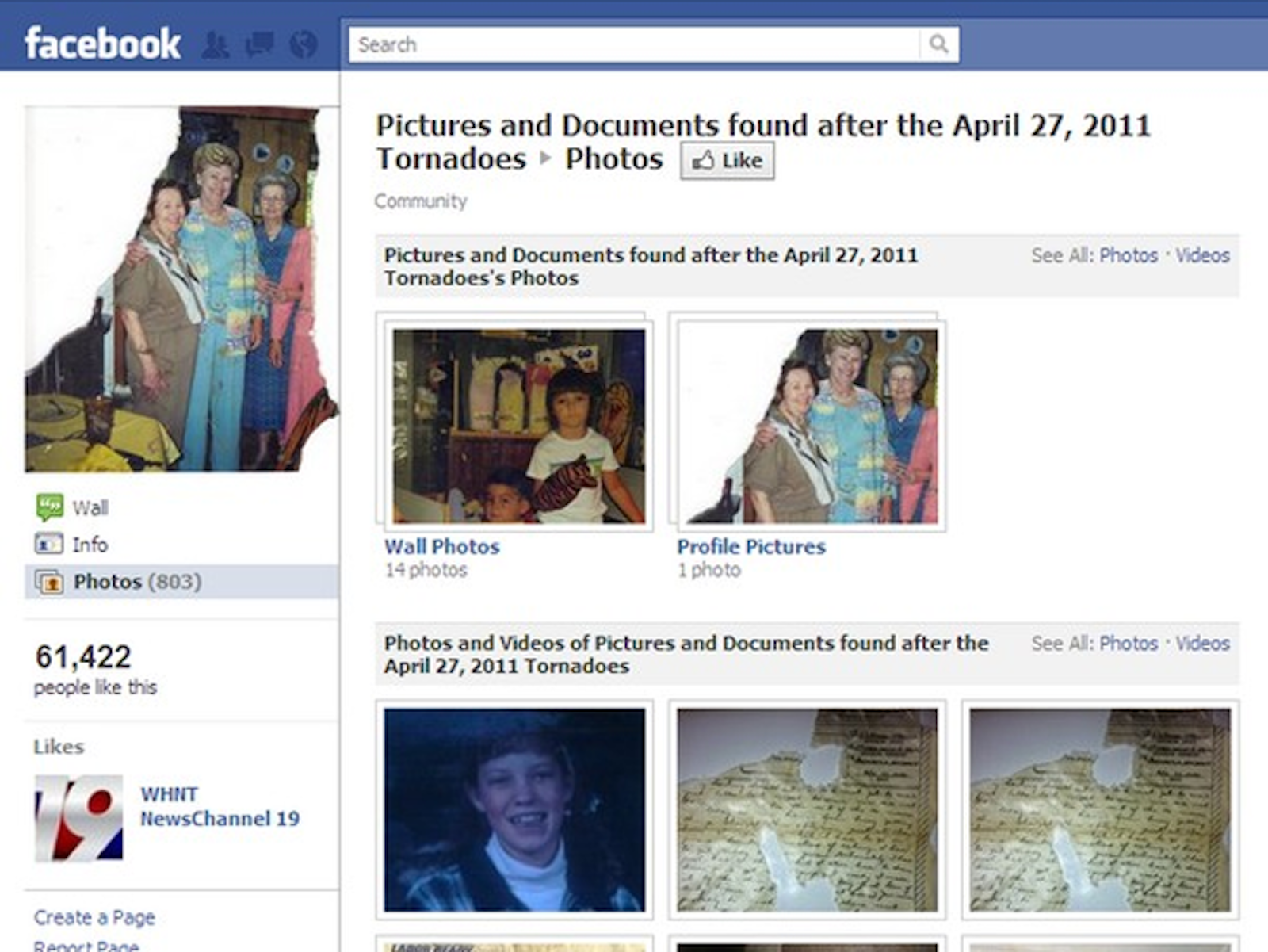

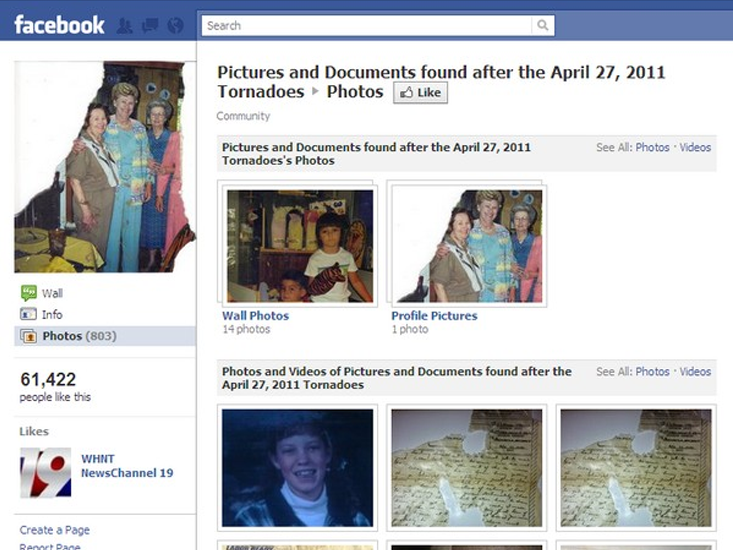

Knox and his team used data gathered from a Facebook page that connected people whose belongings had been whirled up into the April 27 tornadoes with the people who had found the belongings.1 Many items were found more than 100 miles away, including high school letter jackets, homemade quilts, metal signs, canceled checks, and photographs. One photograph, from a trip to Yellowstone, was picked up in Phil Campbell and deposited 219 miles away, in Lenoir City, Tennessee, the longest flight ever recorded for a piece of tornado debris. A 5-foot metal sign commemorating Lee Frederick, a resident of Smithville, Mississippi who died from bone cancer in 1998, was torn from its place above the Smithville High School football stadium bleachers and carried in the air 50 miles northeast to Russellville, Alabama, where Russellville resident Dan Morris found it.

By plugging the starting and ending points for 934 pieces of debris into a computer model called HYSPLIT, initially built to track aerosols, Knox was able to plot how high the tornado debris had gone in the atmosphere: an astonishing 20,000 feet. That’s nearly four miles high, or about two-thirds the cruising altitude of a commercial jetliner. Just how did the debris get that high in the first place?

“There is virtually no literature on that at all,” Knox told me when I posed this question to him, “but I will give you my guess.” First, he hypothesized, an object is blown horizontally out of a structure, then drawn vertically into the air along the outer wall of the tornado, possibly spiraling around the core of the twister as it rises. The debris that takes flight tends to be light and aerodynamic, such as a photograph or a canceled check. Heavier items, such as jackets, quilts, or blue jeans have the advantage that they are flat, and can fan out in the wind and act like a sail. “Jeans could be pretty aerodynamic, if the wind blew through the legs and ‘inflated’ them,” speculated Knox. “Balled-up, rolled-up jeans wouldn’t go as far, in my opinion.”

At some point the debris reaches the base of the thunderhead, called the anvil, where it encounters the jet stream, which carries it along in the same direction the tornado is traveling, which in the case of the April 27 storms was to the northeast. At this point the debris is no longer being uplifted by the storm and begins falling, at a rate of about three feet per second. The stronger the jet stream winds are, the farther away from the starting point the object will be when it hits the ground. The majority of objects that Knox studied fell out roughly 10 degrees to the left of the track of the tornado that carried them, an indication of which direction the winds were blowing at the altitude in which the debris maxed out, said Knox. Objects that were lofted the highest were occasionally deposited to the right of the tornado track, because winds higher up in the atmosphere were blowing in a more easterly direction.

Knox isn’t the first to study the turbulent flight of personal objects caught in a storm. A 1995 paper on tornado debris published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society reported on a Mississippi tornado that carried a couple’s marriage license 30 miles, and a tornado that struck Worcester, Massachusetts in 1953 that carried a wedding gown 50 miles. Emily McNutt, of South Weymouth, found the garment. “It was dirty, as would have been expected,” reports the paper, “but was intact and in surprisingly good condition.”

But these studies had datasets limited to just a few items, scattered between tornadoes from different decades and different places. Knox’s study is the first to examine such a large number of objects with fixed take-off and landing points from a single tornadic event. “This study,” said Knox, “shows just how electronically interconnected we have become.”

Justin Nobel chronicled the 2011 tornado events in his recent feature “Walking the Tornado Line” for Oxford American. Some of his other stories have been published in Best American Travel Writing 2011 and Best American Science and Nature Writing 2014. He lives in New Orleans where he is working on a book of travel stories titled North, South.

Reference

1. Knox, J.A., et al. Tornado debris characteristics and trajectories during the 27 April 2011 super outbreak as determined using social media data. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 1371-1380 (2013).