This summer, I hosted two parties on back-to-back weekends. One was in New York, my hometown; the other in Washington, DC, where I now live. Both were pirate themed. Guests drank rum and wore bedazzled eye patches. In New York, there was even a stuffed parrot that was eerily life-like and managed to spook nearly all members of my immediate family. We may have inadvertently discovered a mild, hereditary phobia of birds. The jury’s still out.

Gimmicks and hijinks included, these parties marked an important anniversary in my life. I am a three-time survivor of pediatric cancer. These parties commemorated a personal cancer-related milestone.

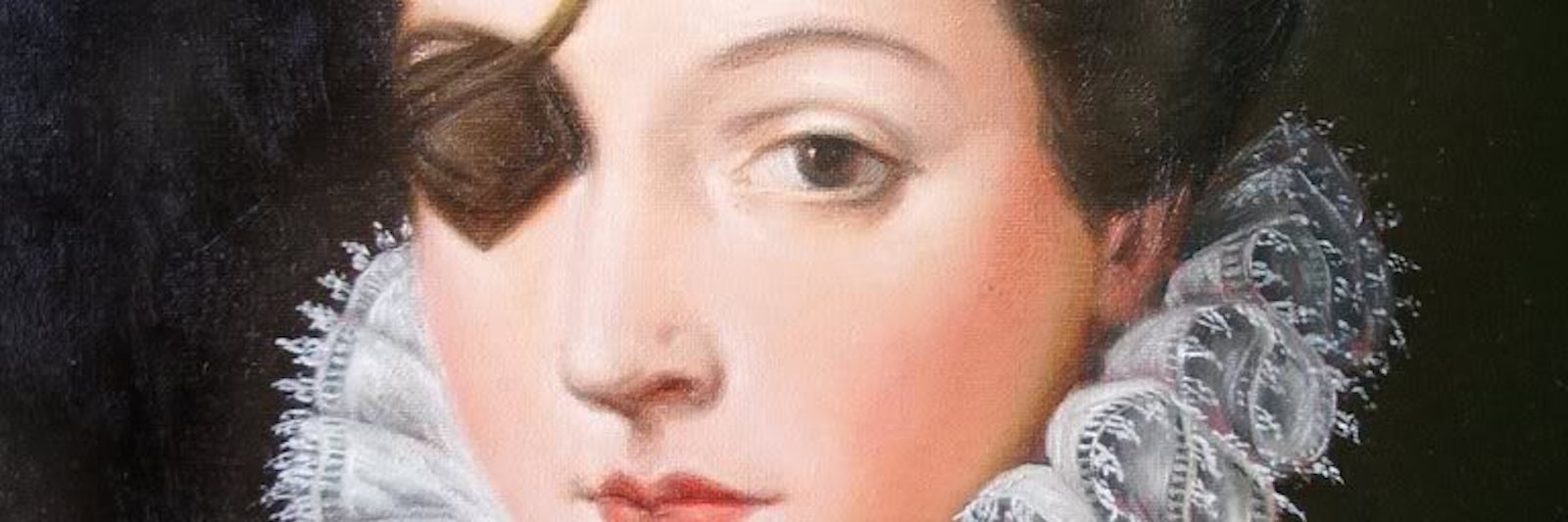

Fifteen years ago, on June 21, 2000, I was 12 years old. I had a bone tumor in my right sinus and, on that day, underwent a 14-hour surgery to remove the tumor. Removing the tumor meant removing the bone structure that supported my eye. This meant my right eye had to go, too. Ever since, I have worn a black eye patch. And this summer, surrounded by family, friends, and that creepy toy parrot, I celebrated my 15th anniversary with my patch.

For me, celebrating my eye patch empowers me to focus on what cancer has given me, rather than dwelling on what it has taken away. I don’t characterize cancer as wholly negative. Nor do I define triumph against cancer in purely medical terms. Instead, I acknowledge the active—and often positive—role cancer has played in making me exactly who I am today.

Like it or not, that single day in June 15 years ago changed my life. I used to be an ordinary, anonymous girl. Now, it seems I can’t hail a cab without the driver remembering that he’s driven me before and recalling my preferred route to the office. Life with an eye patch is different. In many ways, it’s better.

And, for the 6-year-olds, they may actually believe I am a pirate.

I don’t want to oversell this. Wearing an eye patch every day can totally suck. People stare, they make rude comments, and I have never really felt pretty. When I stop and think, the scars I see in the mirror can frustrate and sadden me. There are days when all I want is to blend in and be “normal.”

That’s only a piece of the story, though. My eye patch also invites people in. It fosters human connections. It’s like that awesome piece of jewelry you can wear only every once in a while because everyone notices it. It’s a conversation piece. Except I get to wear mine every day, and it can take a bit longer for the novelty to fade.

This week alone, two complete strangers have asked me outright, “What happened to your eye?” This happens to me all the time; sometimes, I get a “Hello!” first. For years, this constant questioning made me really mad. I felt like I could never hide. I didn’t understand why strangers would ask such a personal question. After fielding this question hundreds of times, though, I have learned that most people are not trying to make me feel bad. Usually the opposite is true.

Turns out, Glass-Eye Guy had the same cancer diagnosis as I did.

Many of these strangers are trying to relate. When I answer their questions directly, many respond with personal stories of cataracts procedures or other related experiences. One guy even popped out his glass eye just to assure me that he wasn’t being a jerk. That was more assurance than I needed, but it worked. He may not wear his scars as openly as I must, but when I realized he had endured similar circumstances, I felt less alone. I felt connected.

There are also inquisitive strangers who are just trying to understand. I have lived with my eye patch for more than half my life. At this point, I’m used to it. But, for the strangers I pass on the street, it may be a first-time encounter. And, for the 6-year-olds, they may actually believe I am a pirate. They may need a second to process me. And that’s okay.

In my view, these strangers are not bad people. I don’t fault them for wanting to connect with another human being or understand something out of the ordinary. In fact, I prefer they hear the truth from me than resort to whatever stories they can drum up in their heads. I have learned to be patient and speak honestly. The results are often richer than I ever could have predicted. (Turns out, Glass-Eye Guy had the same cancer diagnosis as I did.)

Then, there are the strangers who don’t respond to me in words, but in actions. We all know there are certain groups of people for whom we are expected to give up our seats on a crowded subway: children, pregnant women, the elderly. Apparently, for some people, otherwise-healthy 20-somethings with eye patches also make this list.

On the surface, I find this phenomenon amusing. I sometimes joke with myself, “My legs work.” At their core, though, these gestures are genuine. They are sweet. They are examples of people—even hardened New Yorkers—paying attention to other people, and offering what they can.

Reprinted from the Journal of Clinical Oncology