In the 2004 film I, Robot, Detective Del Spooner asks an A.I. named Sonny: “Can a robot write a symphony? Can a robot turn a canvas into a beautiful masterpiece?” Sonny responds: “Can you?”

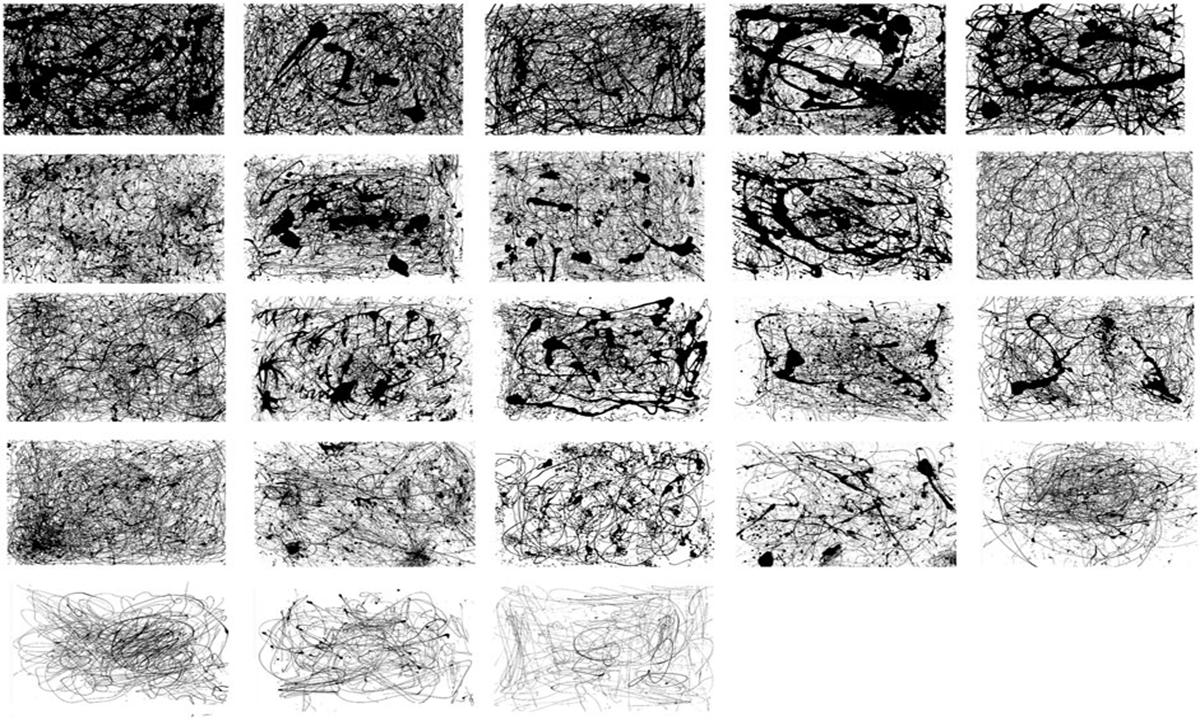

Scientists have been working on answering Spooner’s question for the last decade with striking results. Researchers from Rutgers University, Facebook, and the College of Charleston have developed a system for generating original art called C.A.N. (Creative Adversarial Network). They “trained” C.A.N. on more than 81,000 paintings from 1,119 artists ranging from the 15th century to the 20th century. The A.I. experts wrote algorithms for C.A.N. to emulate painting styles such as High Renaissance, Impressionism, and Pop Art, and then diverge from the styles and produce “arousal” among human viewers.

In a 2017 paper in arXiv, the scientists report that “human subjects could not distinguish art generated by the proposed system from art generated by contemporary artists and shown in top art fairs.” Aiva, a musical A.I., recently became the first machine to be registered as a composer by SACEM, a French professional association of songwriters, composers, and publishers. It learns from existing musical compositions then composes original, emotionally resonant music.

Why have we not seen a robot comedian as sophisticated as a robot composer?

If A.I.s can be creative, can they be funny, too? Eric Horvitz and Dafna Shahaf, researchers from Microsoft, in conjunction with former New Yorker cartoon editor Robert Mankoff, recently showed that an A.I. can tell what’s funny. Horvitz and Shahaf developed an A.I. to help sift through the massive pile of submissions to the New Yorker’s caption contest. “We developed a classifier that could pick the funnier of two captions 64% of the time, and used it to find the best captions, significantly reducing the load on the cartoon contest’s judges,” they wrote in a paper.

Although A.I. robots can pick up on jokes, they have a lot to learn about telling them. Generally their jokes derive from wordplay, puns, and undermining logical expectations. “What do you call a capable seed? An able semen.” Not exactly Robin Williams. But not bad.

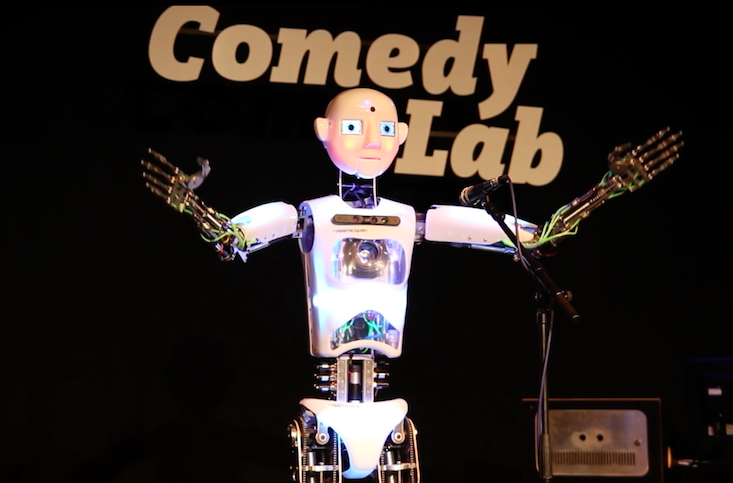

Zoei (Zestful Outlook on Emotional Intelligence), a robot created in 2014 by researchers at Marquette University, shows promise as a budding stand-up comic. Zoei creates jokes and gestures, and detects faces and recognizes audience reactions to previous jokes. It improves its routine via a machine learning technique called reinforcement learning: Much like a human comic using trial-and-error, Zoei maximizes the “reward” (laughter or a positive response) for its jokes by exploring its options and exploiting the best one.

Zoei has to start from scratch with each audience, building up its repertoire as it goes. Human comics do the same thing to some extent, but they can memorize past audiences and make associations between them, as well as write and prepare before performing. Watching a “Zoei Night Live” would be like experiencing the awkward first few minutes of an open mic, or the uncomfortable season pilot, at the beginning of every special.

So far, Zoei has not been tested in larger than one-on-one settings, or across a wide demographic—it’s not close to being a comedic counterpart to Aiva. Why have we not seen a robot comedian as sophisticated or advanced as a robot composer?

The fundamental difference in the building blocks of music and language can explain this discrepancy. According to Jonah Katz and David Pesetsky, from West Virginia University and M.I.T., respectively, these building blocks consist of “arbitrary pairings of sound and meaning in the case of language; pitch-classes and pitch-class combinations in the case of music.” The general arbitrariness of language is commonly accepted as one of its defining features: The sound of a word does not hold implicit meaning on its own, because it can change in the context of the language, dialect, sentence, and so on. Katz explains that “there could be anywhere from seven to a couple dozen types of basic atoms that are combined to make complex pieces of music,” while “for language, the number of basic atoms is on the order of tens of thousands.”

With its intricacies and inflections, meanings and motives, language is the currency of comedy. (Not the only one: See great slapstick comics like the Marx Brothers.) Robert Provine, a neuroscientist and author of Laughter: A Scientific Investigation, has shown the banter that pervades our everyday lives is often the seed of a comedian’s jokes. Provine once observed groups of people on a college campus, for an experiment, to see what provoked laughter. The exchanges that got people to chuckle, Provine found, were akin to an “interminable” TV sitcom “scripted by an extremely ungifted writer.” Comedy depends on quotidian dialogue and shared cultural and social references.

We should be pleased to learn that human language remains our domain. Because its nuances are difficult to capture in A.I., we can be infinitely more creative with it than machines. A robot comic would have to go a long way to generate a deep laugh, let alone a comedy set. At an improv club, it would be the one awkward friend trying out puns and dad-jokes. For now, robots can write jokes that appear on popsicle sticks. But they won’t be upstaging Dave Chappelle anytime soon.

Silvia Golumbeanu is an editorial intern at Nautilus.

WATCH: The roboticist Ken Goldberg on the most creative thing a robot has done.