One question for Sönke Dangendorf, who studies sea levels, tides, storm surges, and coastal flooding at Tulane University’s School of Science and Engineering.

Why is sea level rise worse in some places?

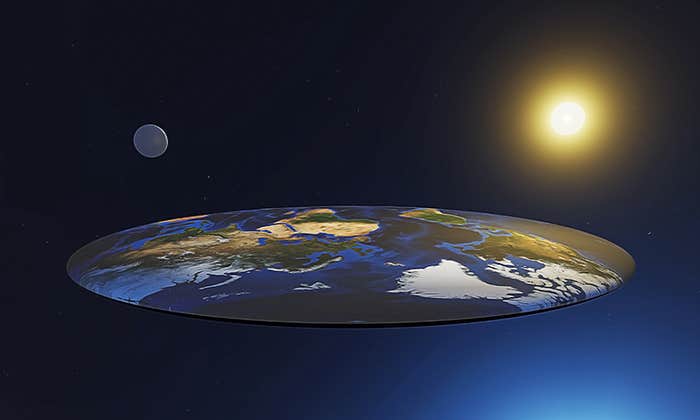

There is sometimes a misconception that the ocean behaves like a bathtub, but that’s not true.

If we look at the global picture, there are two major reasons why sea levels are rising. One is that the ocean is warming, and it needs more space and expands. And the other one is that ice sheets and glaciers are melting, and they put more mass into the ocean.

But if we look locally, there are a lot of factors that lead to regionally varying sea level rise.

We have changes in ocean circulation, and the same is true for winds. Imagine, in the simplest form, winds over the ocean push water masses from one side to the other. That can lead to changes in sea level over several years to decades. The same is true for ocean currents because winds affect ocean currents.

It’s not only the ocean that is rising, but it’s also the land that is sinking.

If we put water into the ocean by ice sheets or glaciers that are melting, their gravitational field is also changed. Here, there are three things that happen: You put mass into the ocean, so sea levels rise globally on average. But then, the ice sheet is a heavy body of mass, and due to its mass, it attracts the water of the surrounding ocean, like the moon generates tides. So as that ice sheet melts you reduce that gravitational attraction, and the water migrates away from the ice sheet. And then at the same time, the weight of the ice sheet also becomes less, and it leads to uplift of the ground below. So it leads to sea level fall near the ice sheets but sea level rise in what we call far-field—like here in Louisiana, for instance.

Then, lastly, in particular here in Louisiana, it’s not only the ocean that is rising, but it’s also the land that is sinking. So we see subsidence, for instance, due to fluid withdrawal like crop water withdrawal and oil and gas withdrawal that have led to subsidence in some areas.

In our study, we saw sea level rise rates in excess of a third of an inch per year from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, to the Gulf of Mexico. These high rates of sea level rise have already had profound impacts on our coasts in the region. For instance, in the Gulf of Mexico, in this period, we have seen a doubling of what we call high-tide flooding events. These “sunny-day floodings” due to sea level rise mean streets and sometimes properties get flooded and lead to considerable damage. We have also seen, in Louisiana in particular, on top of that, local subsidence—much larger rates of Louisiana has been losing land, equal to the entire state of Delaware since the 1930s. This sea level rise has also coincided with record-breaking hurricane seasons. And these hurricanes can build up on a higher base level with these higher sea levels, so that means these events can become more destructive with the underlying sea level rise.

We will continue to see what we have seen in the past, that there have been different kinds of hotspots of sea level change, and they can shift from time to time. They will continue to accelerate in the future, and that means we will see these kinds of hotspots more often. ![]()

Lead image: MainlanderNZ / Shutterstock