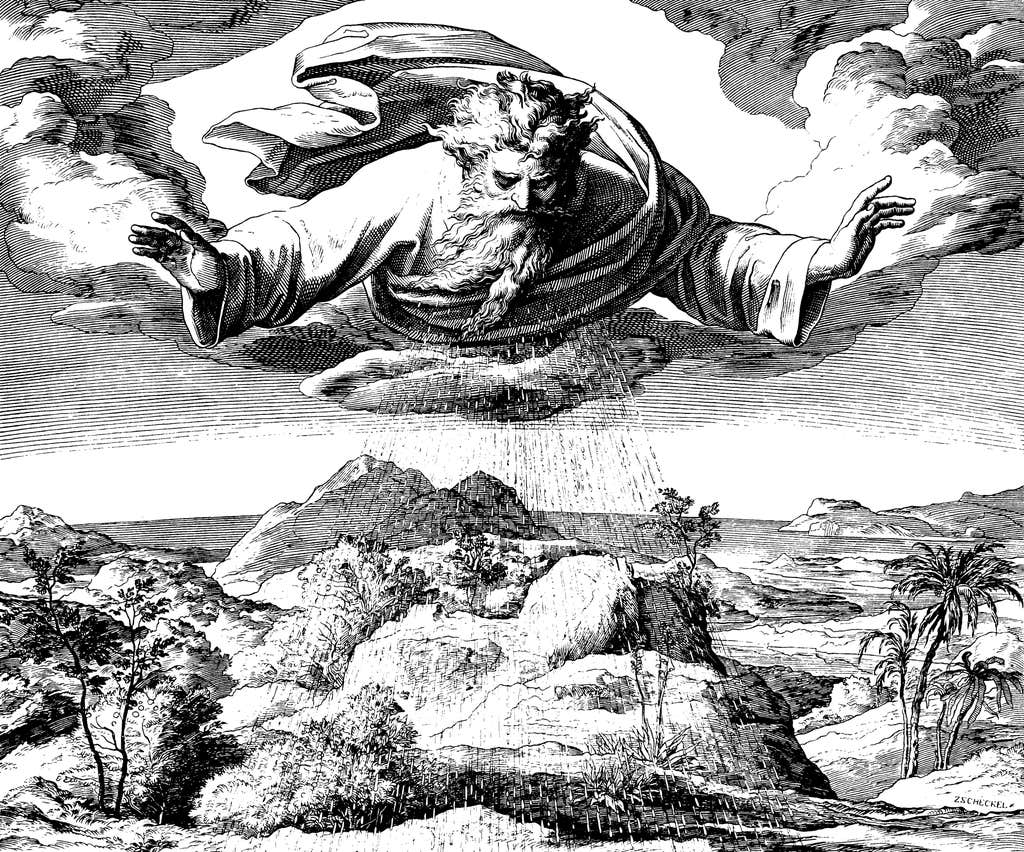

God spent his third day of creation emitting rain from his chest, bringing forth plants from dry land. Or at least that’s how the artist Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld depicted God in his 18th-century engraving The Third Day of Creation. In Schnorr’s image the divine source of rain clearly looks like a human.

Today we’d call this anthropomorphism—the tendency to attribute human characteristics to non-human targets. It’s found in childhood and across the globe. Many people believe in one or more human-like gods, and some go further still: They see the ocean as conscious, they think the wind has intentions, they say mountains have free will. They look at nature and see an aspect of themselves reflected back.

When and why do we do this? A recent study offers new evidence for the role anthropomorphism plays in supernatural explanations. The researchers, led by Joshua Conrad Jackson, a psychologist at Northwestern University, analyzed the ethnographies of 114 culturally diverse societies to track patterns in supernatural explanations across the globe. What they found suggests that when we experience harms that can’t be readily attributed to human beings, our anthropomorphic minds look to human-like supernatural beings instead.

To test their hypothesis, Jackson and his colleagues focused on explanations for six harmful phenomena—three natural (disease, natural hazards, and natural causes of food scarcity, such as drought) and three social (warfare, murder, and theft). For example, the Cayapa People, who live primarily in the rainforests of Ecuador, believe that lightning comes from the Thunder spirit, who can kill people with his sword or its glint. The researchers found that 96 percent of societies had supernatural explanations for disease, 90 percent for natural hazards, and 92 percent for natural causes of food scarcity. By contrast, 67 percent had supernatural explanations for warfare, 82 percent for murder, and 26 percent for theft.

When human agents don’t plausibly explain salient harms, we turn to the supernatural, and we “hallucinate” gods and witches instead.

Someone—angry trees, ghosts, divine beings—is teaching us a lesson.

Anthropomorphism may seem uniquely human, but we can actually gain some insight into its origins from a distinctly artificial source: the way large language models, such as ChatGPT, get things wrong. When ChatGPT encounters a question that closely matches questions and answers from its training data, it provides responses that reflect the training data with high fidelity. But as the match between a novel question and the training data grows more tenuous, it fills in the gaps by producing the answer it predicts would be most consistent with its training data. This process is necessarily imperfect—it requires going beyond the data—and so sometimes chatbots make mistakes. AI researchers call these mistakes hallucinations.

For humans, “training data” is a lifetime of experience, filtered through our mechanisms for learning and inference. When we use our intuitive theory of mind to correctly infer the presence or contents of minds, we extoll our human intelligence. But when we get things wrong—and in particular, when we overgeneralize human properties beyond their human targets—we aren’t so different from a hallucinating chatbot. We want to understand why there’s a drought and our intuitive psychology fills in an answer that fits in with our previous experience of other harms: Someone—angry trees, ghosts, divine beings—is teaching us a lesson.

Of course, for AI researchers to appeal to “hallucination” to explain a chatbot’s mistake is itself anthropomorphic: We’re using our own experience to make sense of AI. The potential for recursion here is heady but also illuminating: The funhouse mirror of seeing ourselves reflected back through AI brings understanding by letting us see the familiar—our own tendency to anthropomorphize—from a novel perspective.

When I asked ChatGPT about Schnorr’s engraving, it explained that “God is shown holding a staff or wand, and he is surrounded by a variety of plants and flowers.” But if you take another look you’ll notice there’s no staff or wand. The AI hallucinated them. In describing an image that depicts the origins of a natural phenomenon—rain—ChatGPT showed a very human-like tendency: It offered a supernatural hallucination. ![]()

Lead image: Tasnuva Elahi; with images by Natali Snailcat and Zdenek Sasek / Shutterstock