It’s not just the color of your eyes, or your gregarious manner that you may pass along to your kids and their kids. What you eat, or don’t eat, can get passed on to your offspring, too—and many generations into the future. But researchers are just beginning to understand how this works.

Descendants of people who faced famines—such as the Dutch Hunger Winter during World War II or the Great Chinese Famine in the 1960s—have long been shown to carry higher rates of health conditions like obesity, diabetes, and even schizophrenia. “We know if the parents face starvation or undernutrition, or if they lack some basic nutrients, that can actually impact embryonic development,” says Giovane Tortelote, an assistant professor of pediatric nephrology at Tulane University School of Medicine.

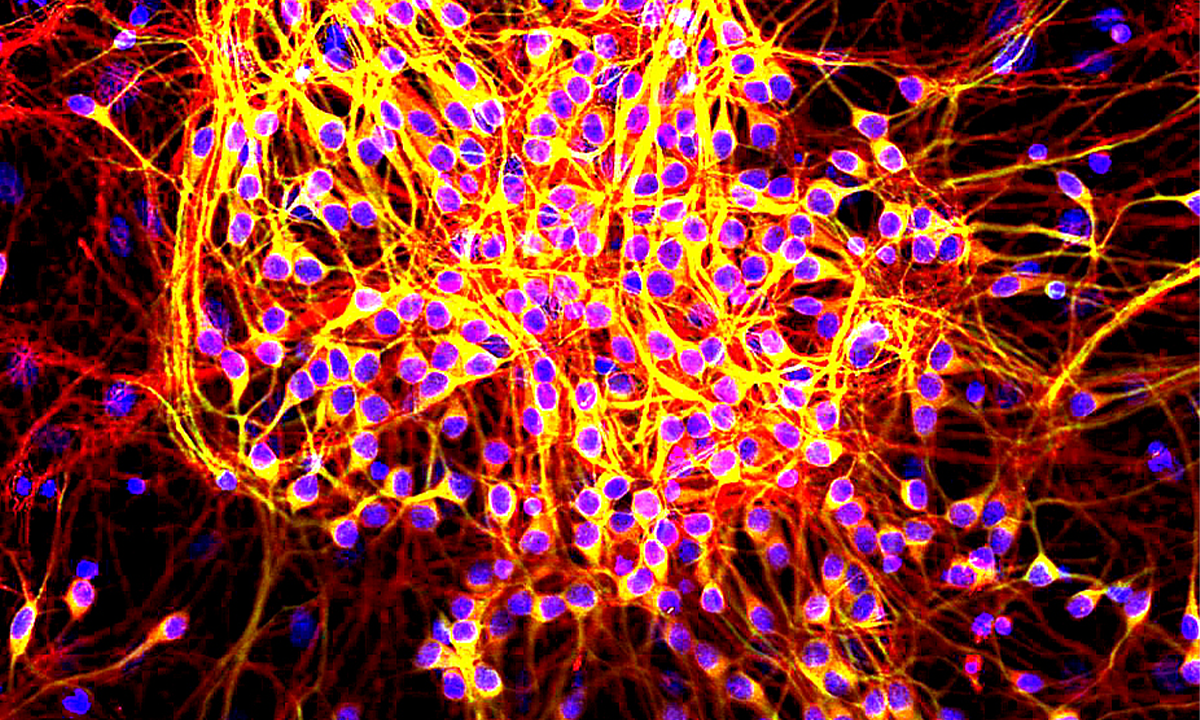

But, he wondered, could undernutrition affect not just an embryo’s development, but also the expression of DNA in the offspring, so-called epigenetic changes that can be passed down? And if so, where in the DNA would this show up and how many generations would be affected, particularly when people were no longer under food stress?

Now new research authored by Tortelote shows that—in mice—a famine-mimicking diet can compromise the health and development of the kidneys of offspring over at least four generations. The research was published in the journal Heliyon.

“This is not genetics, it’s epigenetics.”

It’s not the first effort to show that diet can have impacts on future generations. One study from 2016 demonstrated that when four generations of mice consume low-fiber diets it can cause almost irreversible negative changes to the gut microbiomes of the offspring. And another study found mothers who eat high-sugar, high-fat diets can predispose their offspring to insulin resistance and metabolic problems for at least three generations.

To conduct their research, Tortelote’s lab fed a group of mice a low-protein, high-carb diet—about a third of the protein lab mice normally get in their diet. Very low protein diets have been shown to have a similar physiological impact on the body as famine does. The researchers then studied the mice’s offspring over the next four generations, all of who received normal diets. What they found is that all four subsequent generations had lower birth weights and smaller, weaker kidneys, leading risk factors for chronic kidney disease and hypertension.

The mouse babies suffered low birth weights and compromised kidneys not only when both parents followed a low-protein diet prior to breeding and during gestation, but also when the father alone had a low-protein diet prior to breeding. In other words, a poor diet affected not just the gestation period but genetic inheritance from father to offspring. “That tells you that the uterine environment is important, but it’s also important what comes from the dad—this is not genetics, it’s epigenetics,” says Tortelote.

Tortelote estimates that it could take five or six generations of improved diet for the negative effects of malnutrition on the health of one’s descendants to subside, but determining this would require further research. His lab is also looking into the molecular mechanism by which the epigenetic changes get passed on, and trying to create a supplemental metabolite that could help reset gene expression in the offspring.

He wants to design solutions to lineages of nutritional stress, so that what one’s grandparents ate doesn’t define their health. ![]()

Lead image: K_E_N / Shutterstock