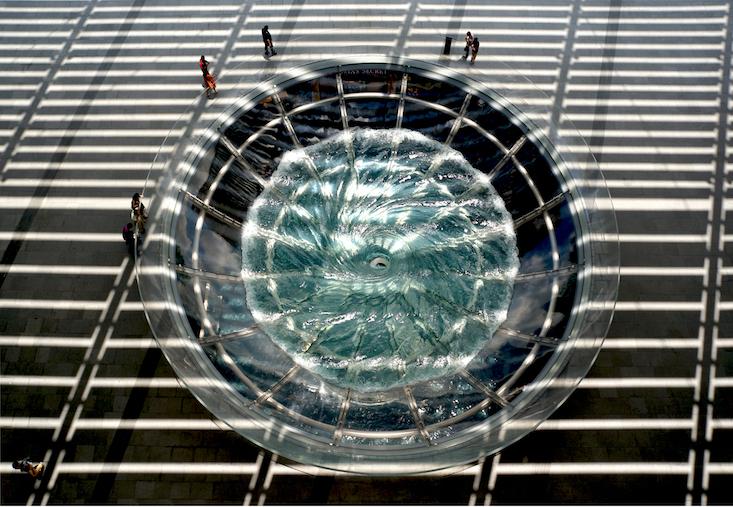

The environmental artist Ned Kahn, a MacArthur Foundation “genius grant” awardee, gravitates toward phenomena that lie on the edges of what science can grasp—“things,” he tells me over the phone, “that are inherently complex and difficult to predict, yet at the same time beautiful.” The weather, for example, has, because of its chaotic yet orderly nature, “fascinated me for my whole career,” he says. For almost the last 30 years in particular, he’s been creating dynamic installations that he thinks of as “observatories”: Since they frequently incorporate wind, water, fog, sand, and light, he states on his website, “they frame and enhance our perception of natural phenomena.”

Take his most recent project, the “Shimmer Wall”. Composed of over 30,000 tiles, it will be a 1,100-foot long façade of a new building, home to the “Ocean Wonders: Sharks!” exhibit, set to open this year at the New York Aquarium (over $80,000, toward a $100,000 goal, has been donated for its construction). It will house over 100 species of animals, including but not limited to a variety of crustaceans, sharks, fish, rays, and turtles. “They were struggling with the façade and someone on the design committee knew about my work and approached me,” says Kahn. “That led to the idea that we’re doing a skin for the aquarium inspired by fish skin, shark skin, scales. I’ve been doing a number of faceted, fragmented, kinetic artworks influenced by scales—that move with the wind and, when you step back, you get an idea of how the wind affects it.”

Kahn tells me that, before Hurricane Sandy hit, on October 29th 2012, there was a six-foot square experimental piece of the Wall outside the aquarium, to test if it could stand extreme weather. It held up perfectly, he says. In his conversation with Nautilus, Kahn also spoke with enthusiasm about how nature both inspires and interacts with his work, as well as what people make of it.

What effect are you trying to produce in observers of your art?

What’s intrigued me over the years is that when you make the wind visible, a certain percentage of people who see it—it kind of stops them in their tracks. It awakens people to the strangeness that we live in an ocean of air. Air is invisible. We forget about it. It becomes commonplace—this crazy substance we constantly breathe to keep ourselves alive. I guess my hope—and I’ve seen it happen many times—is that people have a moment of awakening to the strangeness and mysteriousness of the physical world we inhabit.

Why does much of your work incorporate scale-y surfaces?

I’m just fascinated by the fact that scales are so evolutionarily ancient. In the Precambrian times, the first creatures with hard body parts had scales, appearing amazingly early in animal history. Even today, creatures have so many variations and the design works so well: to cover yourself with a whole bunch of flexible but strong panels that can move individually but also have a cohesiveness in their movement.

A lot of the work I’ve done is inspired by nature and draws its forms from nature and its metaphors. But I don’t see that looking at the façade will teach anyone any important lesson in particular—it’s more of a learning that happens on a sensory level, on a level of wonder and awe. What these facades really start to look like is water—they have this faceted mirror like that of water. Our nervous systems have a harmony with water. It’s soothing to them—rather than disturbing, it has a calming effect.

Did you study real samples of fish anatomy and morphology to prepare for your work?

The extent of it was looking at images of fish scales normally and microscopically, as well as at some microscopic images of the skin of sharks—they have much smoother skin than scaly fish, but if you look at their skin closely, it is also covered with microscales in crazy beautiful shapes. They almost look like a bunch of little hands with fingers on the edges of them compared to traditional fish scales that you think of as kind of half disks. These skins have an architectural quality to them—they are a bunch of different modules, which are fascinating to me. This type of modularity allows you to make tens of thousands of them to be neutral registers to what the environment is doing. A lot of architects try to pretend their buildings are not made by a bunch of little pieces, that they have a monolithic quality to them, but the reality is that they all came on a truck.

What does the curvy, wavy structure of the Wall represent?

It definitely draws some of its inspiration from creatures. It’s a serpentine flow, a very gentle spiral. It’s evocative of shell forms, eels or a long, skinny fish kind of wrapping around itself. The texture is evocative of scales but also, maybe on a deeper level, it touches on the idea of a membrane. Every cell in your body has this really active membrane that is letting food in and wastes out and letting air in and water in. There are these analogies to architecture, like the skin of a building: You want to keep light in but water out, so the whole idea of a permeable membrane has been fascinating to me. This whole exoskeleton for the aquarium is this permeable membrane that allows wind to pass but also absorbs and changes the wind. The wind and the light become linked, so as the wind morphs and changes its façade it allows light to pass through it and enter it; it changes its reflectivity, it touches on what separates life from not life.

Sheherzad Preisler is an editorial intern at Nautilus.