Reprinted with permission from Quanta Magazine’s Abstractions blog.

Like cosmic hard drives, black holes pack troves of data into compact spaces. But ever since Stephen Hawking calculated in 1974 that these dense spheres of extreme gravity give off heat and fade away, the fate of their stored information has haunted physicists.

The problem is this: The laws of quantum mechanics insist that information about the past is never lost, including the record of whatever fell into a black hole. But Hawking’s calculation contradicted this. He applied both quantum mechanics and Albert Einstein’s theory of gravity to the space around a black hole and found that quantum jitters cause the black hole to emit radiation that’s perfectly random, carrying no information. As this happens the black hole shrinks and eventually disappears.

Holographers usually walk down a one-way street from a gravity-filled volume to a quantum flatland, where the math is easier.

But does its information disappear with it, meaning quantum mechanics is wrong? Or does the problem lie with Einstein’s theory? When forced to choose, many physicists back the quantum rule and suspect that information somehow escapes in the black hole’s radiation, which in that case isn’t random after all. Figuring out how the information gets out should point the way past Einstein’s theory to a more complete quantum theory of gravity. Yet after 45 years of grappling with this “black hole information paradox,” no one has pinpointed the alleged misstep in Hawking’s calculation.

Now, though, several noted black hole physicists think they may be closing in on a solution. Not even the researchers themselves fully grasp the physical implications of the math they explore in a recent paper. But in the abstract mathematical threads, they and others see the outlines of a bridge to the black hole’s interior, an escape route for trapped data. They located this hidden path using an imperfectly understood technique for spying on a black hole from a higher dimension.

“It’s magic,” said Ahmed Almheiri, a physicist at the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) in Princeton, New Jersey, who co-authored the recent paper. “We know how to prove” that the shift in perspective works, he said, “but we don’t have a complete understanding of why this is happening.”

Raphael Bousso, a physicist at the University of California, Berkeley and an expert on the information paradox, said of the new work, “I find it interesting enough that I’m really working hard” to understand it.

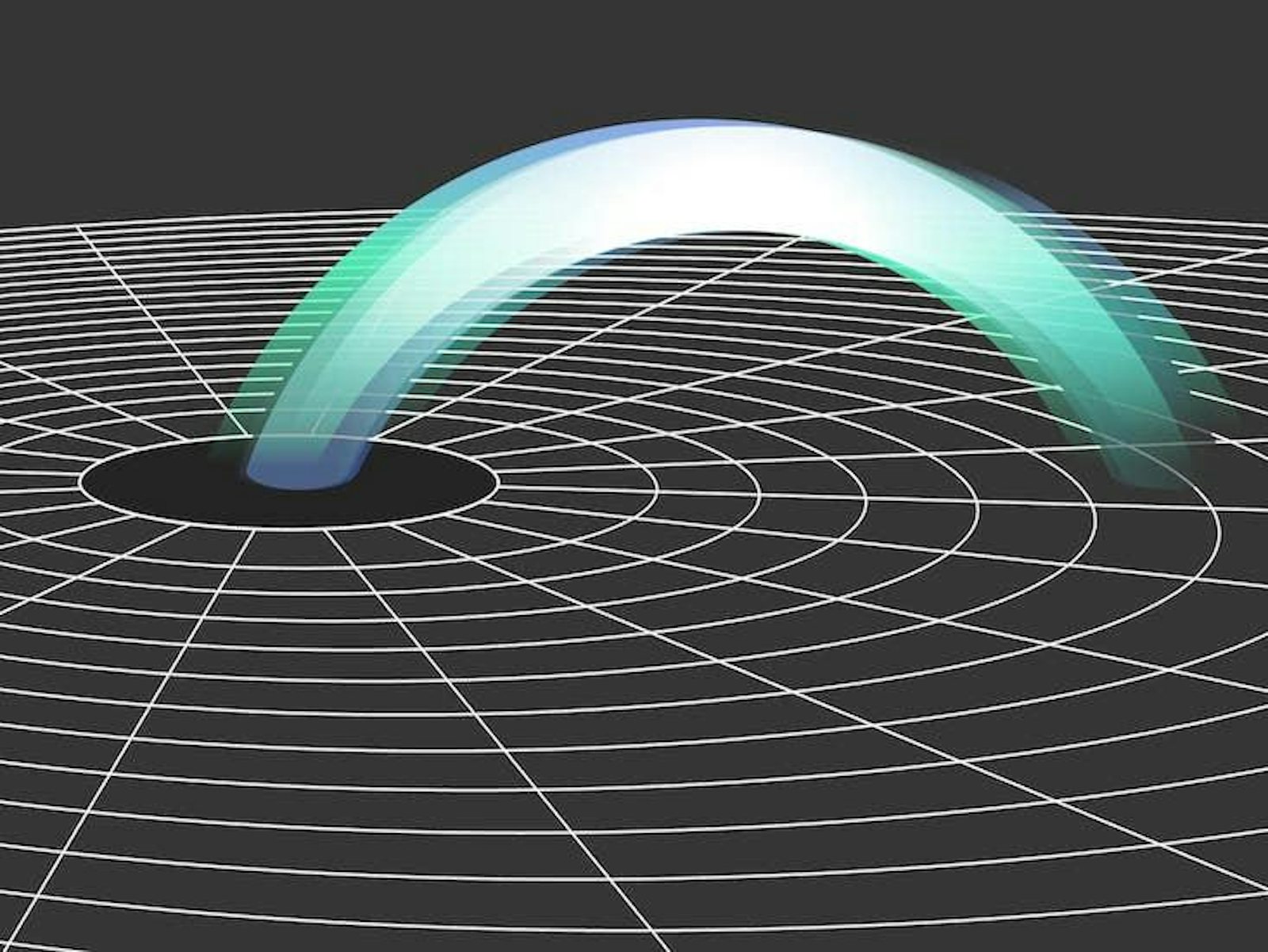

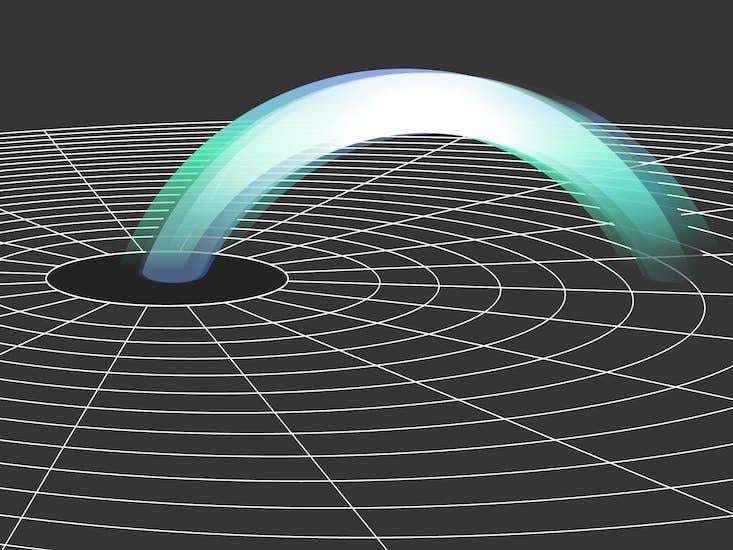

The dimension-hopping technique that’s key to the new development is known as holography. Just like a credit card hologram that pops out from a flat sticker, a system like a black hole can be viewed in two equivalent ways. There’s the familiar view of a black hole as a volume of space in which gravity is so strong, and the fabric of space-time bends so steeply inward, that not even light can climb out. Alternatively, the black hole can be thought of as a holographic projection from a flat system of quantum particles that remains gravity-free. Following the discovery of this duality by Juan Maldacena, a physicist at IAS, in 1997, physicists have peered at many mysteries from these complementary angles. They’re now using the holographic approach to try to track the flow of information through a black hole.

First, a pair of papers that appeared in May analyzed how a black hole’s information content changes as the object ages. In one of the papers, Almheiri and co-authors considered a simplified gravitational black hole in two dimensions that’s equivalent to a one-dimensional system of quantum particles. They found that at first, as the black hole gobbles up matter and gets bigger, its information content increases. But then, in its old age, as radiation starts spitting data back out, its information content decreases, diverging from Hawking’s description. Geoffrey Penington of Stanford University independently came to similar conclusions. The papers found a new way to reproduce the conventional wisdom that information should safely escape black holes, but they stopped short of explaining how it does so — or where Hawking’s math went wrong.

The latest paper, posted online in late August, went further, offering a new way to think about Hawking’s math.

Holographers usually walk down a one-way street from a gravity-filled volume to a quantum flatland, where the math is easier. But in this new work, Almheiri, Maldacena and their IAS collaborators Raghu Mahajan and Ying Zhao tried strolling both ways.

They took a 2D black hole and separately considered its two elements: the matter inside it, and the gravity produced by that matter. As before, they viewed the 2D gravity as the hologram of 1D quantum particles. But they treated the black hole’s matter like the flat part of a second hologram, letting these 2D quantum particles pop into a 3D image. This strategy created an Inception-like hologram within a hologram. “It seemed like it was a really crazy thing,” Almheiri said, “but we took a chance.”

While information appeared trapped in the black hole’s interior in 2D, the researchers found that after the hologram popped off the page, portions of the black hole interior became geometrically linked to portions of the exterior, providing an escape route for information. Consequently, outgoing black hole radiation may look random to a passing astronaut doing simple experiments, Almheiri says, but rigorous study would reveal subtly hidden information—the outcome many have been hoping for.

The holographic connection between the black hole’s interior and exterior supports an old hunch that considering the two together should somehow resolve the information paradox. “They are providing very significant new evidence in favor of that rule,” Penington said.

But experts stress that while the higher-dimensional bridge may let the information out, a detailed account of how it is encoded in the radiation is still lacking. “This is the beginning of a theoretical understanding of what’s going on in terms of radiation,” said Netta Engelhardt, a physicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who worked with Almheiri on the May publication, “but it’s not an operational description for how to extract the information.”

The 3D view also helps clarify why 2D black holes eventually diverge from Hawking’s calculation. The theorists traced the changes in the information content of the black hole by measuring the areas of related geometric surfaces in the 3D hologram. The area of the smallest such surface gives the information content. But as this surface grows, a second one eventually replaces it as the smallest. Continuing to track the first surface reproduces Hawking’s error, but switching to the second one corrects the math by showing that the information contained in the black hole starts to drop.

In this way, the hologram within a hologram gives the desired answer to the question of what happens to a 2D black hole’s information. Most experts assume that if the reasoning is correct, it should carry over to higher-dimensional black holes like those in our universe. A common concern, however, is that the authors might be reading too much meaning into this abstract calculation.

Don Marolf, a physicist at the University of California, Santa Barbara who worked on the spring paper with Almheiri, Engelhardt and Henry Maxfield, praised the new work as a concrete model demonstrating the earlier papers’ claims. However, Marolf worries that holography may not be as wise a guide as Almheiri and Maldacena hope, because it’s possible to hop between dimensions on many different paths. The route found in the new paper seems to work, but Marolf cautions that other holographic constructions might disagree. For this reason, he said, “we’d all like to be able to do something intrinsic to this 2D theory without invoking holography as a magic black box.”

Indeed, in ongoing work, Almheiri’s team and a number of other groups are pursuing a more grounded description that they hope will reach the same conclusions as their hologram-within-a-hologram proof without leaning on the crutch of the extra dimension.

But even if the fancy holography tricks don’t stand, black hole researchers express excitement that Hawking’s information paradox is able to transport them to the boundaries of known physics. “On the map that says, ‘Here be dragons’—the quantum gravity [theory] that we’re searching for—the dragons are a lot closer than we thought,” Bousso said.

Charlie Wood is a journalist covering developments in the physical sciences both on and off the planet. His work has appeared in Scientific American, The Christian Science Monitor and LiveScience, among other publications. Previously, he taught physics and English in Mozambique and Japan, and he has a bachelor’s in physics from Brown University.