In the center of the photo, standing amid dry brush and trees, is something’s butt. I have 50-some animals to choose from, and I’m really not sure whose butt it is—maybe a duiker’s, a small, deer-like creature. “If you see an animal, please mark it,” the instructions say, “even if you’re not sure, or have no idea what it is.” Apparently, any errors will be filtered out. A duiker’s butt it is. Next image.

Flipping through picture after picture of an African landscape, trying to identify any animals caught in the frame, feels more like a session of Chat Roulette than meaningful work. But I’m actually helping sort scientific data. This is crowd-sourced science, and Paola Bouley is using it to solve a particularly modern problem: There’s too much data.

Bouley, an ecologist, has been studying the lions of Mozambique’s Gorongosa National Park since 2012. They were once the park’s main attraction, but its wildlife was decimated by the country’s 15-year civil war, which ended in 1992. Today, while its herbivores seem to be recovering, its lions remain scarce. Studying them is also hard: More than 80 percent of the park is inaccessible by road, making field studies a challenge.

“We figured out how to turn all of that volunteer effort into expert-quality scientific data.”

To fill in the gaps, Bouley placed motion-triggered cameras in their habitat near watering holes and along game trails. The cameras provide valuable information about the lions, their prey, and even poachers, but they present their own problem; by 2014, she’d collected more than 230,000 photos, overwhelming her staff’s ability to sort through them. “It becomes,” she says, “a very time intensive operation.”

Enter the internet. “People have spent 15 billion hours on Angry Birds. [They] have a ton of free time.” So says Ali Swanson, an ecologist at Zoonivese. As a graduate student at the University of Minnesota, Swanson also used motion-triggered cameras to study animals in Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park. Like Bouley, she quickly found herself deluged with data. Seeking a way to deal with more than a million unsorted photographs, she approached Zooniverse, a citizen-science nonprofit started in 2007 by two Oxford astrophysicists who had their own set of millions of photographs (of galaxies) needing classification. So the pair built a website and called on the public for help. By the third day, thousands of volunteers were making 60,000 galaxy classifications every hour; by the end of the first year, they’d made 50 million classifications.

Inspired by their example, Swanson partnered with Zooniverse to build her own website, called Snapshot Serengeti. By the end of its third day of operation, tens of thousands of volunteers had made more than a million classifications. “They processed an eighteen-month backlog of data in the first week,” she says.

What’s more, they were accurate. Zooniverse created a “gold standard” data set of 4,000 images for Snapshot Serengeti, all classified by a team of experts. Compared to that gold standard set, she says volunteers’ collective classifications were accurate 97 percent of the time. “We figured out how to turn all of that volunteer effort into expert-quality scientific data.”

Bouley followed in the footsteps of Swanson with WildCam Gorongosa, also built and hosted by Zooniverse, in partnership with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

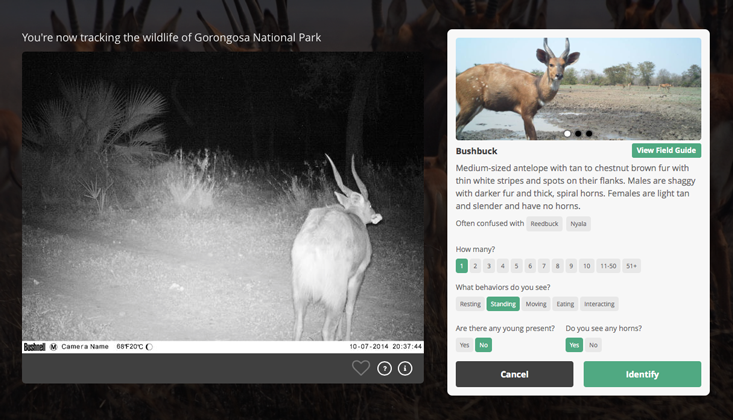

WildCam Gorongosa’s classification page features a photograph captured by one of Bouley’s field cameras next to a list of 50 large animals (including humans), plus “Fire” and “Nothing here.” If it’s obvious what the animal in the photo is—a warthog, say—you click warthog. If it’s hard to tell which animal you’re looking at, you can choose the best-fitting animal silhouette (a cat, a zebra, a deer, a monkey, a weasel, or a bird), the best of four fur patterns, six colors, four horns, and five tails. Then: How many were there? Were they resting, standing, moving, eating, or interacting? Were any young present? Click, click, click. Done, next image. From start to finish, it usually takes about 10 to 30 seconds. After 25 people have identified the contents of a photo, it is taken out of circulation, and the program determines which classification got the most votes.

Since WildCam Goronogosa’s launch last Tuesday, thousands of volunteers have made more than 350,000 classifications—that is, someone has already looked at each photograph at least once. An initiative by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute will draw out even more data from the photos, allowing users to layer the data by species, time of day, wet or dry season, and more. Intended primarily for high school biology and ecology educators, the website, set to launch in April 2016, will also be useful for scientists researching elephants, primates, and other species in the park, says Dennis Liu, head of education media at the Institute.

So the Internet horde appears willing—though what motivates it isn’t clear. WildCam isn’t a game, exactly—there’s no reward if I correctly identify an animal, and no punishment if I screw it up. Yet, I found myself wanting to continue wading through it. Of the first 25 or so photos I looked at, about seven of them were empty. It’s pretty easy for grass or a waving branch to tip off the motion sensors, Bouley says. But I also saw a lot of animals: one elephant, one impala, one civet, a bunch of baboons, a whole bag of warthogs, plus one close-up of a man’s khaki-ed crotch. Most of the time it was only vaguely entertaining, but every once in a while I saw something really unusual or surprising—just often enough to keep me going.

Swanson says that Zooniverse tried rewarding volunteers, giving them virtual badges for completing tasks—but she says it actually discouraged people from participating. People spend the time because they want to feel that they’re contributing to science, she says. Perhaps making it a game diminishes that feeling. The content is an important part of the appeal, too, she says. “People like fuzzy animals.”

But maybe it also tickles a darker impulse. “It’s like gambling—‘The next good one I get, I’m done,’” one early volunteer told me. “’I really, really want a bushpig!’”

Zach St. George is an editorial intern at Nautilus

Gorongosa Park: Rebirth of Paradise premieres on PBS September 22nd.