For most of us, it’s easy to overlook life’s changeability. Each day’s events unfold with enough regularity that we believe we are on a stable path, more or less protected from calamity. But for people with bipolar disorder, the days are tinged with uncertainty. Life as they know it could change completely within a month or two, as they are caught in the rush of a manic episode or the suffocating hopelessness of depression. People suddenly lose jobs, relationships, and good reputations, and the damage is lasting.

The power to interrupt their cruel cycle of mood swings may soon lay in the smartphones in their hands. Researchers at the University of Michigan have begun developing an app that warns a person with bipolar disorder of an impending mood swing. Using speech data collected from the user by the phone, the team is looking for subtle signs in the sounds of a person’s voice that predict an episode of depression or mania. Early detection, before a person has lost awareness of their condition, could prompt them to get medical help and avert the devastating aftermath of a mood episode.

“When someone is in a full-blown manic state, their insight is gone. They’ll tell you that they’re absolutely fine, that things are so great they just bought five new cars and a Greek island,” says Melvin McInnis, a psychiatrist leading this effort. “But if we had gotten to them two weeks before, then they would say, ‘Yeah, you’re right, I was starting to wind up.’”

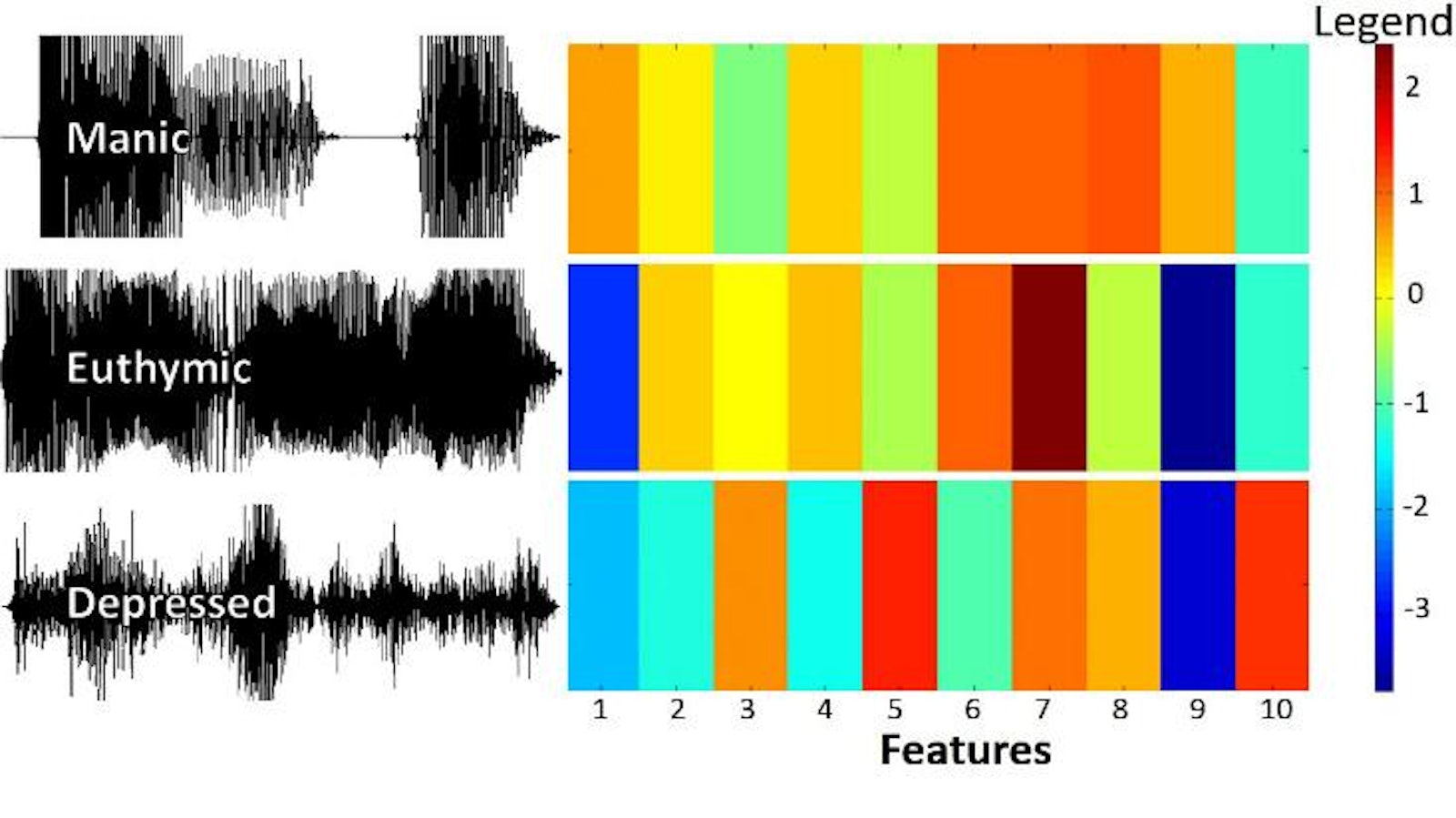

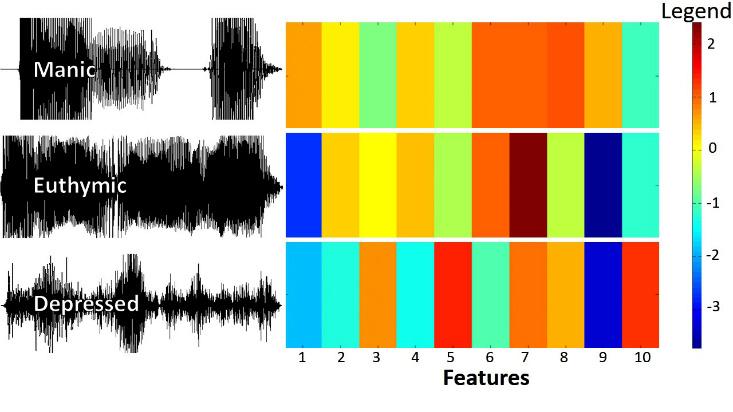

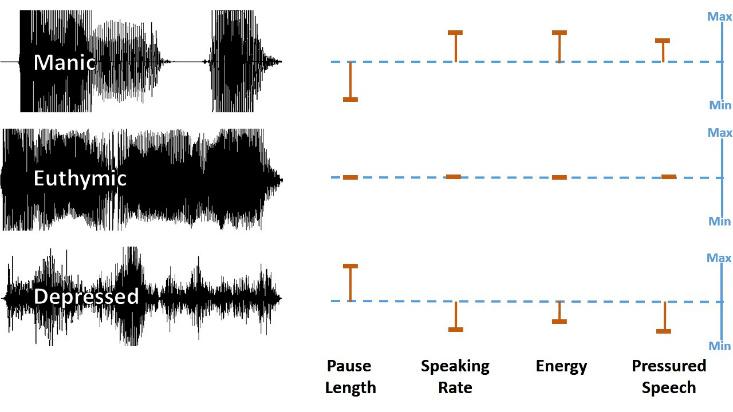

Mood colors how we all say things, but this is especially pronounced in mood disorders. A person mired in depression talks slowly, with long pauses between words, in a monotonous, and possibly hoarse, voice. For them speaking seems a chore. When gripped by mania, however, a person speaks rapidly and loudly, with a sense of pressurized urgency. They struggle to convey all the thoughts whooshing through their brains. Researchers have started to extract features of speech that discriminate different levels of depression severity, which may provide early indicators of whether antidepressants are working.

“It’s important to think of an episode of bipolar mania or depression like a recurrence of cancer or a heart attack. It causes incredible personal devastation, and it’s potentially lethal.”

But McInnis is interested in the transition period preceding states of mania and depression. With computer scientists Emily Mower Provost and Zahi Karam, also at the University of Michigan, he has started the PRIORI project to analyze speech waveforms for features like pitch, loudness, and tempo that may predict a mood swing in the near future, before any recognizable change in mood emerges. For example, a single feature, like loudness, may flag a person on the path to mania or depression once it crosses some threshold. Or telltale signs could come from a combination of these features, or the way they change over a few days. The project was funded in 2013 by the National Institute of Mental Health, so it’s still in its early days. Though they don’t yet know what will make the best predictors, the researchers have come up with an algorithm that estimates the probability that a snippet of speech came from a depressed or manic state.

So far 10 people with bipolar disorder are carrying smartphones loaded with the researchers’ speech-collection software. This will expand to 60 people, all of whom are “rapid cyclers” enrolled in the Prechter Longitudinal Study of Bipolar Disorder also led by McInnis, which follows individuals over several years to document their mood fluctuations. Every two months or so, a rapid cycler crests with mania or bottoms out in depression, so over the long study period, they will provide abundant data on transition periods.

“When someone is in a full-blown manic state, they’ll tell you they just bought five new cars and a Greek island…But if we had gotten to them two weeks before, then they would say, ‘Yeah, you’re right, I was starting to wind up.’”

None of the subjects has balked at carrying a device that snoops on their side of all of their phone conversations, maybe because there’s so much at stake. “It’s important to think of an episode of bipolar mania or depression like a recurrence of cancer or a heart attack,” McInnis says. “It causes incredible personal devastation, and it’s potentially lethal.”

Michele Solis is a freelance science writer living in Seattle, Washington.