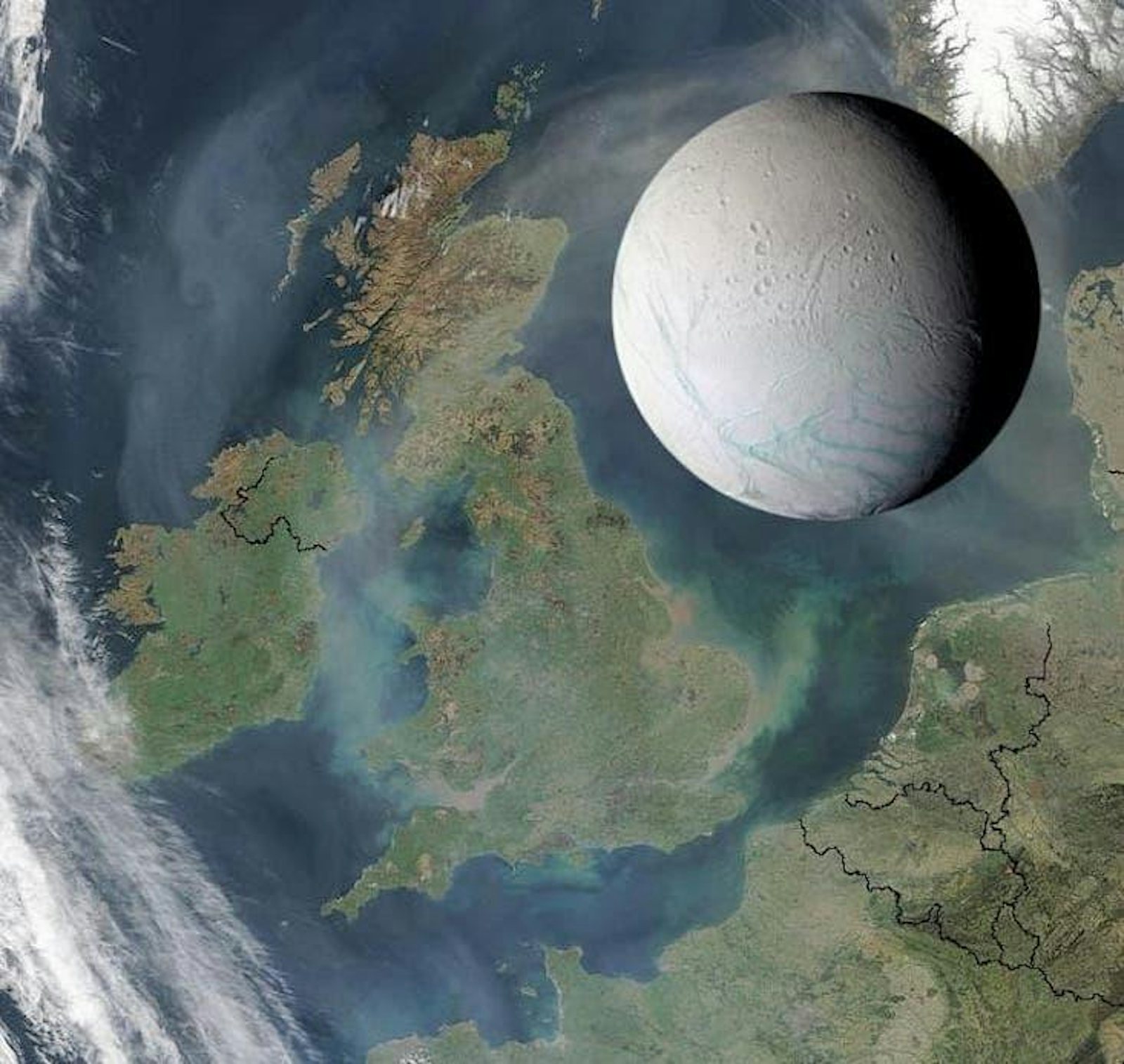

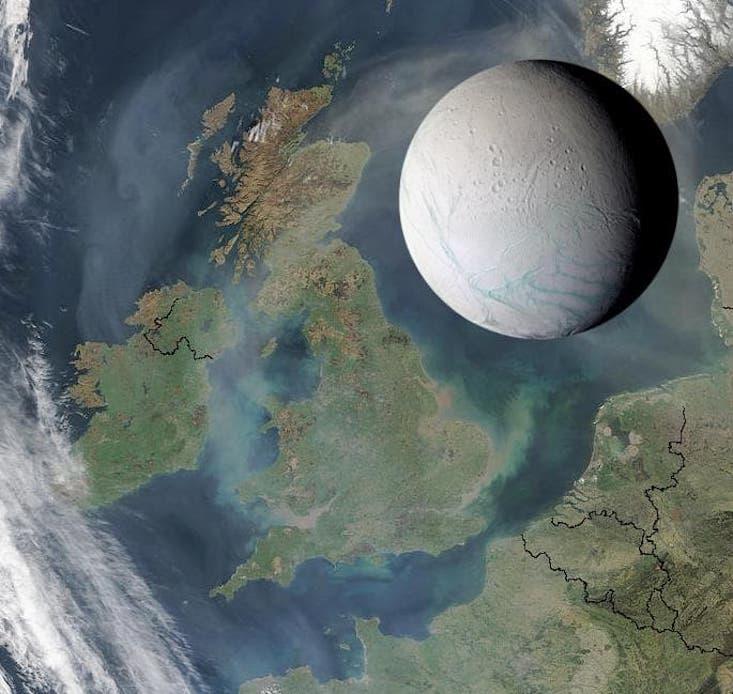

Beneath the icy surface of Saturn’s sixth-largest moon, Enceladus, an ocean dwells. Traces of it get expelled skyward through cracks in the crust via cryo-volcanic plumes. What’s found in the ice grains and vapor are nothing less than the rudiments of life. “We are, yet again, blown away by Enceladus,” Christopher Glein, a space geoscientist at the Southwest Research Institute, in Texas, said, remarking on the findings he and his colleagues reported this month in Nature. They found in the data gathered by the Cassini spacecraft evidence of complex organic molecules with masses well above those discovered in prior analyses. “We must be cautious,” Glein went on, “but it is exciting to ponder that this finding indicates that the biological synthesis of organic molecules on Enceladus is possible.”

The news reminded me of a line from Ice: Nature and Culture, a new book by Klaus Dodds, a professor of geopolitics, that surveys our relationship with ice. “There is no reason to think that we will not make further discoveries of ice throughout the solar system,” he writes, “and perhaps these will act as an imaginative counter-weight to ongoing stories about earthly losses.” He means that the vanishing of our own store of ice in the polar regions and elsewhere, as a result of climate change, is also a depletion of a source of the numinous. “High and cold places are intimately connected to the imaginative, even the spiritual,” he writes. “Up and above the cloud line, mountains offered a sort of transcendence from earthly concerns and the white landscapes of the Alpine, Arctic and Antarctic environments provoked in the Western Romantic traditions an appeal to the sublime.”

To imagine the absence of these landscapes produces something like the opposite feeling, a pang of emptiness and a longing to appreciate that terrain in person before it passes. The prospect is not necessarily a far-off one. Christine Dow, a glaciologist at the University of Waterloo, said, commenting on a new study she co-authored, “We are learning that ice shelves”—thick, floating sheets of ice permanently attached to a landmass—“are more vulnerable to rising ocean and air temperatures than we thought.”

Another new paper, titled “Choosing the future of Antarctica,” conveys a similar sense of alarm. It outlines two possible, polar-opposite paths we could take—one good, the other not so much—toward the year 2070. It’s also written from the perspective of someone from each future, sizing up what went right and wrong. The lead author, Steve Rintoul, an Australian oceanographer and climate scientist, said we don’t have much wiggle room on the path to a good future. “Greenhouse gas emissions must start decreasing in the coming decade to have a realistic prospect of following the low emissions narrative and so avoid global impacts associated with change in Antarctica, such as substantial sea level rise.” His co-author, Martin Siegert, a British glaciologist, added, “Damage there will cause problems everywhere.”

Some of the damage is already irreversible, like the loss of ice shelves. Once they calve off, it is almost impossible to put them back. In the bad, high-emissions future, we’ve allowed this to ramp up. “The large number of icebergs produced by collapsing ice shelves all around Antarctica,” the authors write, “is now carefully monitored to manage the risks to the greatly expanded fishing, tourism and commercial shipping fleets, and Antarctic operations by Antarctic Treaty nations.” Watching a withering continent, we find a silver lining in economic productivity.

In the good, low-emissions future, we have no need to exploit the area. “Motivated by a clearer appreciation of the threats to the region and the global value of better understanding Antarctica and its links to lower latitudes, the parties [to the Antarctic Treaty] reaffirmed the commitment to maintain Antarctica as a natural reserve for peace and science…”

Which future we choose for ourselves depends on our capacity for something psychologists call self-transcendence, the ability to care about the distant future at least as much as your own, more proximal, future. In a recent neuroimaging study, researchers investigated the neural mechanisms that underlie our ability to evaluate future events. “Thirty-six participants viewed a series of events, consisting of potential consequences of climate change, which could occur in the near future (around 2030), and thus would be experienced by the participants themselves, or in the far future (around 2080),” they write. They saw the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, a brain region above the eyes that encodes the personal significance of future events, increase its activation when the subjects saw images of a far-off future wrecked by climate change. “Importantly, this activation increase was observed only in participants with pronounced self-transcendence values measured by self-report questionnaire, as shown by a statistically significant interaction of temporal distance and value structure,” the researchers write. “These findings suggest that future projection mechanisms are modulated by self-transcendence values to allow for a more extensive simulation of far future events.”

Tobias Brosch, a psychologist at the University of Geneva and the study’s lead author, says people can get better at envisioning the ramifications of climate change. “We could imagine a psychological training that would work on this brain area using projection exercises,” he said. “In particular, we could use virtual reality, which would make the tomorrow’s world visible to everyone, bringing human beings closer to the consequences of their actions.”

A less direct but perhaps also effective use of V.R. might be to bring Enceladus to life. What better spur to self-transcendence could there be than visiting its distant and mysterious ice fields and geysers, and being reminded of the universal connection between the future of ice and the future of our own planet?

Brian Gallagher is the editor of Facts So Romantic, the Nautilus blog. Follow him on Twitter @brianga11agher.

WATCH: Stories about a life spent searching for life among the stars.