The deep sea is a part of our planet unlike any other. Accounting for over 95 percent of Earth’s living space, it is cold, dark, and under extreme pressure, yet an astounding variety of creatures abound.

Although relatively little is known about the biology and behavior of animals in the deep sea—defined as beginning at 650 feet down, where sunlight ceases to penetrate, and stretching to the bottom of trenches nearly 7 miles below the ocean’s surface—our ability to observe and study them has never been greater. Over the past half-century, the development of remotely operated vehicles, deep-sea cameras, and deep-submergence vehicles have made it possible for people to get up close and personal with the squishy, spiny, fluorescent, and fantastical residents of this mysterious world.

In recent years, scientists have made great progress gathering high-resolution photos and videos of deep-sea organisms for all to see. In doing so, they hope to show the world that “the deep-sea is not this barren, lonely, dark place where nothing survives,” says Alan Jamieson, a world-renowned marine biologist at Newcastle University. “There are incredible animals down there.”

Here are a few deep-sea species that capture the imagination.

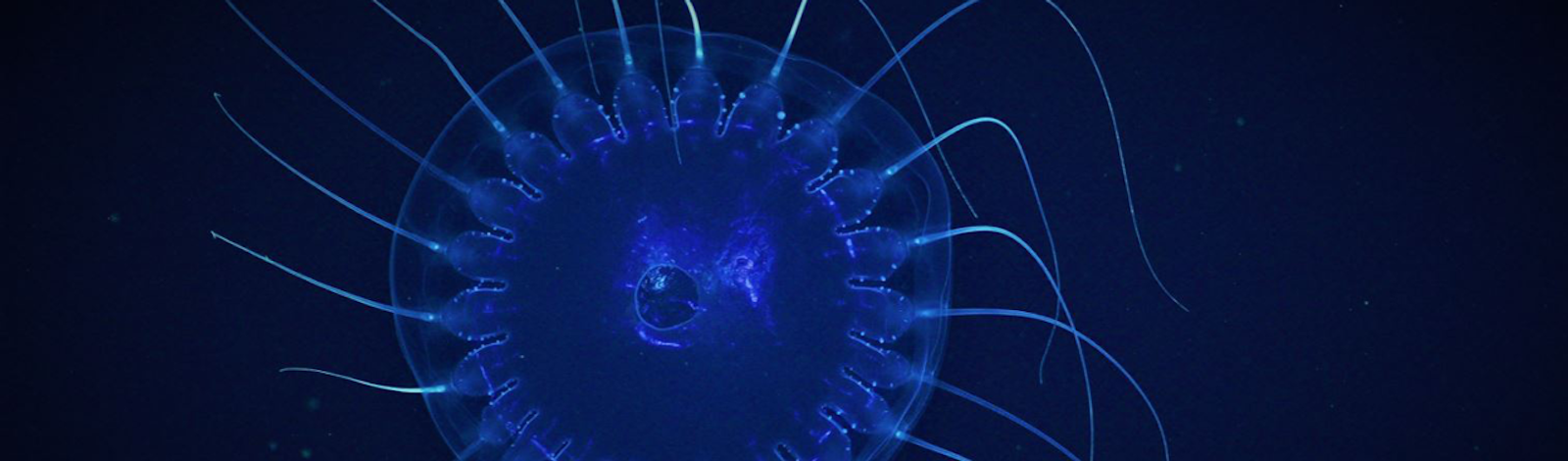

Giant larvaceans, which average about 4 inches from head to tail, live inside giant orbs of mucus, known as houses, that can reach up to 3.3 feet in diameter. Like all larvaceans, the giant larvacean builds its house by secreting a sticky, snot-like substance from cells on its head.

When a giant larvacean flaps its tail to swim, water—up to 20 gallons per hour—is pumped through its house, which acts as a filter for food particles. When these houses become oversaturated with particles that are too large to eat, larvaceans discard them and start constructing new ones. Discarded houses sink to the seafloor where they are eaten by scavengers such as sea cucumbers. Most of the particles that get caught in a mucus house are carbon-rich, so every time a larvacean discards one, it is actually sequestering carbon. And because the carbon is unlikely to return to the atmosphere for millions of years, their constant house-shedding actively combats climate change.

“Most people have never heard of them but they’re one of the most important animals out there,” says Tommy Knowles, a senior aquarist at Monterey Bay Aquarium who has spent years working with larvaceans. “They connect trophic levels and deliver carbon and nutrients to the deep sea. They’re so awesome, so beautiful but so underappreciated.” Researchers with the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute photographed this particular larvacean in Monterey Bay at a depth of roughly 850 feet.

This ram’s horn squid was captured on video for the first time ever in October of 2020 by researchers aboard Schmidt Ocean Institute’s vessel Falkor. Despite the name, this animal isn’t technically a squid, but rather a cephalopod. The “ram’s horn” refers to a spiraled internal shell that serves as its skeleton. They average around 1 to 3 inches in length and have a light-producing organ atop their mantle that allows them to send visual signals in the darkness of the deep.

The researchers were conducting geologic and biologic surveys of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef when they saw this animal at a depth of nearly 3,000 feet. The previous day, the same team of researchers had discovered a coral reef taller than the Empire State Building.

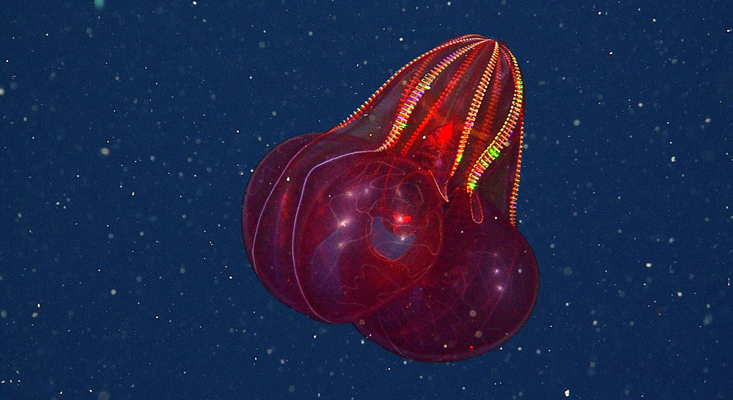

The bloody-belly comb jelly is one of the deep-sea’s most vibrant gems. The name of this ruby-colored ctenophore, discovered by Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute researchers in 2001, was inspired by the creature’s blood-red tissue. The bloody-belly comb jelly’s bright red color may make it easy for remotely operated vehicles with lights and cameras to spot it, but its color actually helps it hide from predators. The color red is nearly invisible in the deep sea, allowing the jelly to not only conceal itself but also any bioluminescent organism being digested in its stomach.

Like all comb jellies, which are not technically jellyfish, bloody-belly comb jellies move by beating the iridescent, hair-like cilia that line their bells. Blood-belly comb jellies have only been found at depths between 980 and 3,320 feet deep in the Pacific Ocean. Researchers with the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute photographed this bloody-belly in 2019 more than 1,600 feet below the surface of the Monterey Bay.

In April of 2020, as Schmidt Ocean Institute researchers explored the depths beyond the west coast of Australia, they encountered what might be the world’s longest animal: a 390-foot long Apolemia siphonophore. For context, blue whales are, at their largest, only about 100 feet from tip to tail.

Siphonophores are gelatinous colonial organisms comprised of hundreds, sometimes thousands, of individuals known as zooids. Different types of zooid have different roles in the colony: some handle propulsion, others buoyancy, digestion, and asexual reproduction. Siphonophores can be found all over the world in deep and shallow waters, but the record-setting Apolemia was discovered at a depth of about 2,000 feet.

The dumbo octopus is the deepest-dwelling, and arguably the cutest, genus of octopuses. All 13 species have skin connecting their tentacles and ear-like fins that they flap to “fly” through the water. They have been found at depths exceeding 10,000 feet and it’s believed they can live even deeper. Unlike most octopuses, dumbos don’t have ink sacs, perhaps because they have very few predators in the deep sea. Dumbo octopuses can be found all over the world, but this one was found off the coast of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef in October of 2020 by scientists aboard the research vessel Falkor at a depth of around 3,000 feet.

Scientists aboard Falkor discovered the translucent, scaleless Mariana snailfish in 2014 while surveying the Mariana Trench, the deepest place on Earth. They dubbed the new species Pseudoliparis swirei, a tribute to Herbert Swire, the 19th-century biologist and navigator who helped discover the trench.

These extremophiles only grow to be around 11 inches long, but despite their small size, they are among the top predators of their realm. They consume tiny crustaceans hidden in seafloor sediment.

The Mariana snailfish has been found at depths beyond 26,000 feet. Only one other fish, a closely-related Mariana Trench-dweller called the ethereal snailfish, has ever been found deeper. As scientists continue to push the boundaries of deep-sea exploration, it’s likely that they will continue stumbling upon other undiscovered creatures at these extreme depths.

“The more we look, the more we will find,” says Jamieson.

Annie Roth (@AnnieRothNews) is a freelance science journalist based in Santa Cruz, California. She enjoys writing about endangered species and the people who study them.

Lead image: Dinner plate Jelly. Credit: Schmidt Ocean Institute

This article was originally published on our Oceans Channel in May 2021.