In 1909, a United States Forest Service officer named Aldo Leopold shot a mother wolf from a perch of rimrock in the Apache National Forest in Arizona. It was a revelatory moment in the life of the young naturalist. “In those days we never heard of passing up a chance to kill a wolf,” Leopold wrote in an essay called “Thinking Like a Mountain,” later included in his Sand County Almanac, published posthumously after his death in 1948 and which went on to sell several million copies. “We reached the old wolf in time to watch a fierce green fire dying in her eyes. I realized then, and have known ever since, that there was something new to me in those eyes—something known only to her and to the mountain.”

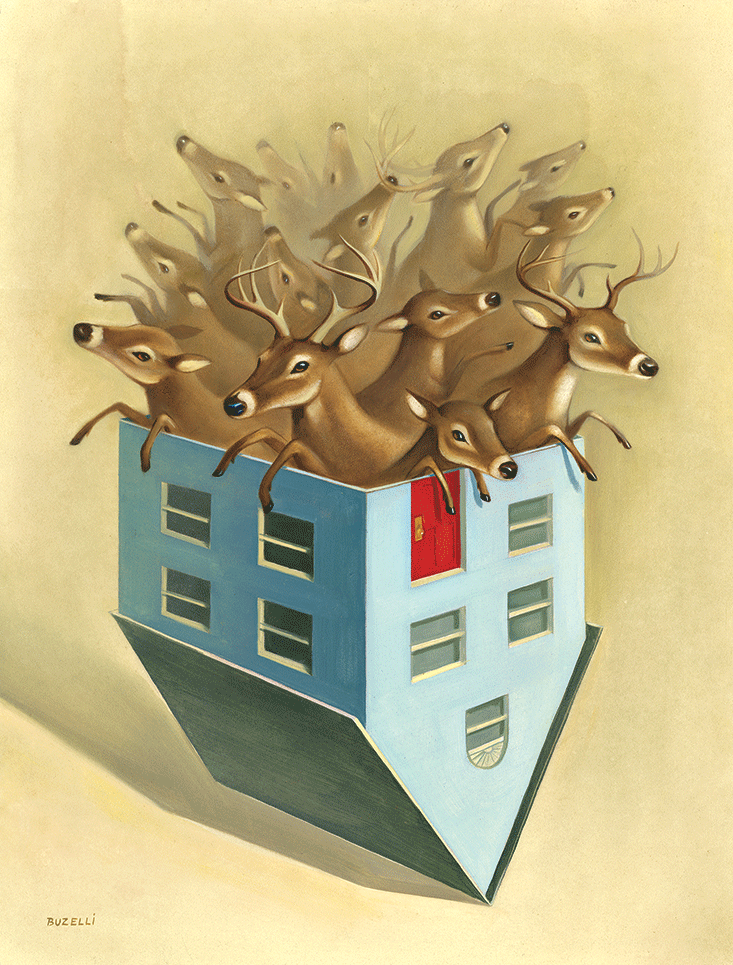

Leopold, who today is revered among ecologists, was among the earliest observers of the impact of wolves on deer abundance, and of the impact of too many deer on plant life. In “Thinking Like a Mountain,” he outlined for the first time the basic theory of trophic cascades, which states that top-down predators determine the health of an ecosystem. The theory as presented by Leopold held that the extirpation of wolves and cougars in Arizona, and elsewhere in the West, would result in a booming deer population that would browse unsustainably in the forests of the high country. “I now suspect that just as a deer herd lives in mortal fear of its wolves,” Leopold wrote, “so does a mountain live in mortal fear of its deer.”

One of the areas where Leopold studied deer irruptions was the Kaibab Plateau near the Grand Canyon. By 1924, the deer population on the Kaibab had peaked at 100,000. Then it crashed. During 1924-26, 60 percent of the deer perished due to starvation. Leopold believed this pattern of deer exceeding the carrying capacity of the land would repeat across the U.S. wherever predators had been eliminated as a trophic force. By 1920, wolves and cougars were gone from the ecosystems east of the Mississippi—shot, trapped, poisoned, as human settlement fragmented their habitat— and they were headed toward extirpation in most parts of the American West. Within two generations, the hunting of deer had been heavily regulated, the calls from conservationists had been heeded for deer reintroduction throughout the eastern U.S., and swaths of state and federally managed forest had been protected from any kind of hunting.

Freed both of human and animal predation, however, deer did not follow the pattern predicted by Leopold. Instead of eating themselves out of house and home, they survived—they thrived—by altering their home range to their benefit. As recent studies have shown, certain kinds of grasses and sedges preferred by deer react to over-browsing the way the bluegrass on a suburban lawn reacts to a lawnmower. The grasses grow back faster and healthier, and provide more sustenance for more deer. In short, there has been enough food in our forests, mountains, and grasslands for white-tailed deer in the U.S. to reach unprecedented numbers, about 32 million, more than at any time since record-keeping began.

He looked at me as if the point was obvious. “Deer, like humans,” he said, “can come in and eliminate biodiversity, though not to their immediate detriment.”

In 1968, Stanford biology professor Paul Ehrlich predicted that another widespread species would die out as a result of overpopulation. But he was spectacularly wrong. Like the deer, the steadily ingenious Homo sapiens altered its home range—most notably the arable land—to maximize its potential for survival. As Homo sapiens continues to thrive across the planet today, the species might take a moment to find its reflection in the rampant deer.

Conservation biologists who have followed the deer tend to make an unhappy assessment of its progress. They mutter dark thoughts about killing deer, and killing a lot of them. In fact, they already are. In 2011, in the name of conservation, the National Park Service and U.S. Department of Agriculture teamed up with hunters to “harvest” 3 million antlerless deer. I asked Thomas Rooney, one of the nation’s top deer irruption researchers, about the losses in forest ecosystems overrun by deer. “I’d say the word is ‘apocalypse,’ ” Rooney said.

On a warm fall day last year, I went to see Rooney, a professor of biology at Wright State University, in Dayton, Ohio. In his office, I noticed a well-thumbed copy of Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb, and I asked him if he thought a comparison might be drawn between human overpopulation and deer overpopulation. He looked at me as if the point was obvious. “Deer, like humans,” he said, “can come in and eliminate biodiversity, though not to their immediate detriment.”

We took a walk through the university’s 200-acre “biology preserve,” its tall hardwoods bounded on all sides by the city’s bucolic suburbia. The afternoon sun stippled the understory, the autumn leaves were just turning, the colors yet to peak, and the sight, it seemed to me, was splendid. Rooney said the reserve was doomed. Saplings of almost all the native trees—shingle oaks, walnut, white ash, elm—were stunted or dying from the over-browsing of too many deer. The forest, he said, would never regenerate if deer went uncontrolled.

Rooney bent to his knees and held the leaves of a white ash sapling three feet in height. Most of the leaves had been chewed away, reduced to nubs. “Deer ruins,” said Rooney. “It might have three, four years left. It can’t eat enough sunlight without leaves.” We stopped at a ragged elm sapling that stood perhaps a foot tall. Maybe it would grow to three feet, said Rooney. A few paces away we found wild ginger, which deer in the preserve had only begun browsing. The deer were working down to plants they had hitherto avoided. “They’ll successively work down to everything they can eat,” said Rooney.

He told me about a study published last year in Conservation Biology that bemoaned “pandemic deer overabundance,” language suggesting the creature was a disease on the land. Ecosystem damage becomes apparent at roughly 15 deer per square mile, and the damage grows with density. Some areas of the northeast host as many as 100 deer per square mile. (The Wright State University reserve has a density of around 40 deer per square mile.) He noted a 2013 article co-authored by a group of Nature Conservancy scientists who warned that “no other threat to forested habitats is greater at this point in time—not lack of fire, not habitat conversion, not climate change.”

Researchers at Cornell University last year concluded that one-third of the forests in New York State had been “so heavily compromised as a result of excessive herbivory” that the hardwoods failed to recruit new saplings for the replacement of older generations. These over-browsed forests consisted only of the middle-aged, the old, and the dying. There were no young folk among the trees. A 2005 report from British Columbia’s Haida Gwaii archipelago found that the predator-free islands, where deer have had the run of the place for more than 50 years, contained 85 percent fewer shrubs and herbaceous plants than deer-free islands. On Anticosti Island, in Quebec, deer feasted so remorselessly on currants, gooseberries, and wild fruits that the native bear population, dependent on the fruits for survival, died out within 50 years of deer introduction. This was astonishing. A prey species, by stealing away plant resources, had extirpated its predator. In Pennsylvania, researchers in 1994 and again in 2012 found that songbird populations crashed as a result of deer destroying the understory where the birds nested.

I asked Rooney about the remarkable ability of deer to thrive in their home range—most of the U.S.—while producing ecosystem simplification and a biodiversity crash. In his own studies of deer habitats in Wisconsin, Rooney found that only a few types of grass thrive under a deer-dominant regime. The rest, amounting to around 80 percent of native Wisconsin plant species, had been eradicated. “The 80 percent represent the disappearance of 300 million years of evolutionary history,” he said. He looked deflated.

A turkey vulture pounded its wings through the canopy, and in the darkening sky a military cargo plane howled in descent toward nearby Wright-Paterson Air Force Base. Rooney and I emerged from the forest onto a campus parking lot where Homo sapiens held sway. The self-assured mammals crossed fields of exotic bluegrass under pruned hardwoods surrounded by a sea of concrete, tarmac, glass, and metal. There were no flowers except those managed in beds. There were no other animals to be seen except the occasional squirrel, and these were rat-like, worried, scurrying. The Homo sapiens got into cars that looked the same, on streets that looked the same, and they were headed to domiciles that looked more or less the same. This is home for us.

A few days later, I called up a former U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist named Leon Kolankiewicz, who has written extensively about human overpopulation and biodiversity, to ask about the effect of 7 billion human beings on wild flora and fauna. Habitat for these wild creatures, he said, is being destroyed, fragmented, or degraded. Animals and fish are poached, overhunted, overharvested. Ecosystems are contaminated with toxic pollutants, and invasive species are deliberately or unwittingly introduced. Earth, as biologist E.O. Wilson has noted, is in the midst of a sixth mass extinction. (There are five others in the geologic record, stretching back 500 million years.) “Extinction is now proceeding thousands of times faster than the production of new species,” Wilson writes.

Kolankiewicz offered a perverse angle of hope for the human race in the midst of this carnage. Loss of biodiversity may not threaten the survival of our species. “Hypothetically, we could survive for quite some time on a simplified planet,” said Kolankiewicz. “Deer are a good analogy. Throughout human history, populations have invaded and colonized new ecosystems, hunted and displaced other species, have caused massive losses of biodiversity, and went on to survive in these depauperate settings.”

The optimist, surveying our advances, has only to smile and conclude that we have happily launched ourselves beyond the constraints of carrying capacity.

Take the human invasion of North America circa 13,000 years ago, when the wise ape, adept with deadly technology and savvy in methods of cooperative hunting, succeeded in wiping out in a few hundred years the megafauna that had ranged across the continent for hundreds of millennia. North American man went on to stake his home ground and thrive on a continent shorn of its most majestic predators and herbivores. Take the examples of the rise and remarkable success of every large-scale agricultural civilization in pre-modern history, from the Mayans in the Americas to Egypt and Sumer and China. These civilizations, with high population densities, commandeered vast raw resources—land, space, soil, water, nutrients—for the intensive cultivation of grain crops, and biodiversity was clobbered in the march of progress. They thrived for hundreds of years—until collapse was precipitated by the usual factor: their own too-muchness, the breaching of the limits of carrying capacity, their home overwhelmed.

The optimist, surveying our advances of the last century, has only to smile and conclude that we have happily launched ourselves beyond the constraints of carrying capacity. If human population doubled between 1804 and 1927, and doubled again between 1927 and 1974, and almost doubled again to 6.9 billion today, with the latest forecasts projecting more than 10 billion people by 2100, we can look to nanotechnology, genetically modified crops, antibiotic feed supplements for livestock, more efficient transportation networks, unconventional oil deposits, safe nuclear energy, wind and solar arrays, smart grids, and much else in the techno-arsenal to keep the human species from crashing. In the perennial face of collapse, “innovation resets the clock,” said Geoffrey West, a physicist, and expert in social systems, at the Santa Fe Institute. How long can the clock of innovation tick? Who can say? Again and again, time has proven the Malthusian pessimists wrong. Like the deer without its predators, Homo sapiens has remade its home range to its benefit.

A few weeks after I met with Rooney, I went into the Catskill Mountains of New York State to visit my family’s vacation home. The place, hanging for dear life on three mountainous acres, is a drafty board-and-batten cabin, about 10 by 15 in size, with no running water, no toilet except the forest, no electricity. Home might be a generous description. As a young man I had installed a wood stove, and had gotten in the habit of escaping from New York City to spend weekends there, writing by candlelight, stoking the fire to keep warm during the freezing nights, bushwhacking in the spring green-up. At the time I thought that I was privileged to watch the workings of a healthy ecosystem.

My mother had told me that when she bought the property in 1971 it held swamp maple, oak, hemlock, birch, yellow poplar, beech, hickory nut, ash. Our five hemlocks have died. The birch are tall and middle-aged or old and dying, as are the hickory nut and the ash and the poplar and the beech. The grandfather of the trees on the property, a fat gnarled oak personality like something out of Tolkien, fell over last summer in what must have been a terminal act of colossal noise. The dense forest that I remembered as a kid to be impassible, the understory full of walls of green and few paths, was now open and easy-going. I found only a few saplings, and those were chewed away, pitiful, bent. Rooney had told me in the Ohio woods that “home for the deer is now a lot less interesting place.” And for us too.

Christopher Ketcham is a contributing editor at Harper’s Magazine.

This article was originally published in our “In Our Nature” issue in December, 2014.