A few years ago, I went to an astrologer as research for a radio show exploring strange beliefs. Vishal knew only my name, and date and place of birth, and didn’t tell me anything terribly profound until I asked him about the car I had just bought. He tapped something into his laptop. I waited.

“I see two cars in your future,” he said.

I laughed. “Does that mean I’ve bought a dud?”

“I can’t tell you that,” he said.

A fortnight later, a mechanic phoned while working on my new car. He informed me I had indeed bought a dud, and suggested I return the car, get my money back, and buy another one.

I bought a second car. Two cars. It’s just a coincidence, isn’t it?

The basic premise of astrology is the stars and the planets exert an influence over events on Earth. The stars’ and planets’ exact influence depends on their motions and relative positions, such as when they appear close together in the sky. If we had all the data about how the sky looked when you were born, say, we could use it to say something about your future, your personality, and maybe your best course of action over the next few weeks, months, or years.

To the informed scientific mind—a relatively new phenomenon—astrology can’t possibly work. That’s because these heavenly bodies are nothing more than agglomerations of rock, dust, or gas. There are distant influences from the stars and planets, but they’re called the gravitational and electromagnetic forces. The gravitational force creates an attraction between masses. Electromagnetic forces transmit light, heat, magnetic attraction, and repulsion. There is a pull on Earth due to these bodies’ masses, and we see the light (and, in the sun’s case, feel the heat) they emit. That’s it. They certainly have nothing to say about the purchase of motor vehicles by science writers with a Ph.D. in quantum physics but no ability to spot a dodgy used car. Why would they?

Newton bought a book on astrology but couldn’t make sense of it. So he began to study Euclid.

Some might walk away at this point, seeing no value in discussing astrology. However, astrology is a vital part of our human, and scientific, story. We have been making astrological connections—mapping the heavens and trying to discern their influence on the Earth—for much longer than we have been doing science. And with very positive results: Astrology had a huge influence on the development of science, sometimes directly. In 1663, Isaac Newton bought a book on astrology at the Sturbridge Summer Fair. It was an act of curiosity, but Newton found that he couldn’t make sense of it because he didn’t know enough geometry. And so he began to study Euclid. This is how Newton got hooked on mathematics.

Most of the influence has been more subtle. Astronomy, for example, arose as an attempt to do better astrology. The 16th-century astrologer and mathematician Jerome Cardano even taught the public to read the skies for themselves, publishing a primer on astronomy within his 1538 astrological guide. “One who wishes to attain knowledge of the stars must begin with knowledge of the planets,” Cardano explains. And so he lays out the movements of the known planets, and instructs the reader on how to find each of them in the sky. He was, according to the Princeton scholar Anthony Grafton, “a 16th-century counterpart to Patrick Moore or Carl Sagan.”

Cardano is the first astrologer mentioned in A Scheme of Heaven, a fascinating new book by Alexander Boxer, a data scientist with a Ph.D. in physics. In the book, Boxer explores the difficult relationship between science and astrology. He honors the latter as “the ancient world’s most ambitious applied mathematics problem, a grand data-analysis enterprise.” It involved gathering thousands of years of observations of heavenly motion, and the concomitant earthly events—whether they be births, deaths, kingdoms lost, or riches gained—into enormous datasets. Throughout its history, Boxer writes, astrology has aimed high, looking to produce “nothing short of a systematic account linking the nature of the heavens to our own human nature.” Like ancient AI, it was the job of astrologers to identify patterns in the gathered data and extract meaning from the correlations they found. Who can blame them if they sometimes saw patterns and meaning where there were none?

It’s not even as if they were blind to this possibility. An underappreciated fact about astrology is that many of its practitioners never fully believed in it. Cardano, for one, wrote a great deal about the inaccuracies of the astrological art (as well as the possibility that it was all a great delusion). And he was far from alone. The great astronomer Tycho Brahe produced astrological interpretations of supernovae and comets and horoscopes for his patrons, but also wrote criticisms of astrology. The same is true of Johannes Kepler. All of these great minds saw the failed predictions, the problematic ambiguities, and the claims based on insufficient data.

But while many astrologers were conflicted about the claims they were making for astrology, few had the economic resources to ditch it entirely. Boxer details a conversation between the poet and scholar Francesco Petrarca and his astrologer friend Maino Maineri. At the time they are both working for the Visconti family who ruled Milan, but Petrarca relentlessly ribs Maineri about the inadequacies of his astrological service. You can’t even use the stars to predict next week’s weather, he says, how can you possibly advise our boss about business and military strategies? Maineri’s reply is almost heartbreaking: “My opinion about this is no different from yours, my friend, but this is how one must live here.”

Petrarca would appreciate the modern experimental confirmations of his suspicions, such as the one published in Nature in 1985. Called “A double-blind test of astrology,” it compared astrologically inferred personality against personality assessments made by psychologists. The astrologers were given a natal chart and three psychological assessments, one of which came from the person whose natal chart was under scrutiny. Astrologers correctly matched the natal chart with the psychological assessment only 34 percent of the time. In statistical terms, they did no better than pure random chance.

Boxer has expanded the available data again by examining four datasets in two experiments. One test involved comparing the timings of road traffic fatalities against astrological suggestions regarding the best moment to travel. The second stacked Renaissance investment advice against data from the Dow Jones Industrial Average. In neither case was there any indication that astrologers, for all their thousands of years of data mining, have stumbled across useful patterns.

An underappreciated fact about astrology is many of its practitioners never fully believed in it.

Boxer has tried his best to help astrology out by mining the most complex datasets he could find. One frequent criticism, for instance, is that two individuals can have wildly different life experiences despite being born with identical, or near-identical, astrological identities. But perhaps, Boxer says, the astrological identity is just not well-enough defined.

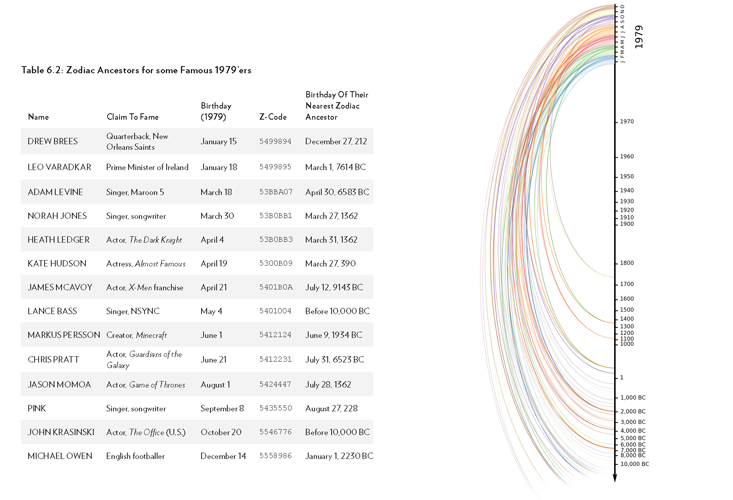

Boxer’s contribution here is the “Zodiac code,” a string of seven alphanumeric characters, based on the eight contributors to an individual’s horoscope drawn up by second-century Hellenistic astrologer Vettius Valens. The Zodiac Code, or Z-code, is a shorthand description of the positions of the heavenly bodies at the time of a person’s birth. There are 44,789,760 different Z-codes, Boxer says. It sounds like a lot, but each Z-Code can be shared by upward of 30,000 people on Earth. It is hard, then, to claim that astrology can offer predictions or advice that are unique to the individual. But, Boxer suggests, perhaps its power lies in making certain moments unique, or at least rare.

To test this, Boxer created a data-dump of historical Z-codes. From 10,000 B.C. to today, Boxer calculates, there has been a total of 30,180, 228 “distinct astrological moments.” It is surprising how rarely they repeat. For instance, the last time someone with the actor Heath Ledger’s Z-code appeared on Earth was in the year 1362 (they were born on March 31). Boxer’s own Z-code last appeared on May 20, 2669 B.C., when Imhoptep was building Egypt’s first pyramid. An unfortunate who was thrown to the lions, as documented in Vettius Valens’ second-century A.D. Anthologies, has shared a Z-code with no one since: The next person with that code will be born on March 30, 3328.

Is it enough to give astrology some credibility? No. A horoscope can only serve as “a cosmic reminder” of how unique each moment is. “It’s awe-inspiring and humbling to consider that the configuration of the heavens on our birthday, or any given day, will almost certainly never repeat in our lifetime,” Boxer says. “Even the sum of human history has played out against a backdrop of just a small fraction of astrological possibilities.” But the bottom line is that there is no discovered pattern that backs up the suggestion that these possibilities have affected human lives in any way. The data gives astrology nothing.

In the end, Boxer, like me, doesn’t think there is any reason to believe in astrology—but we are both Tauruses, so what can you expect?

In fact, throughout history, philosophers and scientists have always charted the world with the available data of the time—and they have always got things wrong.

“Men will from time to time revert to darkness out of boredom with light,” said the 17th-century philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Leibniz in an essay he wrote at the beginning of the 18th century. “Ours is such a time,” he went on, “with great opportunities to learn the right things being spurned, and a wealth of the most lucid truths being disregarded in favor of obscure trivialities.” Leibniz was a champion of sober thought, a mathematician clever enough to invent calculus at the same time as Isaac Newton. His essay was called “Against Barbaric Physics” and railed against a resurgence in magical thinking. Physics stripped of all mysticism is “too clear and simple for these people,” Leibniz complained. “How can any reasonable person today subscribe to a belief in fantastic qualities that is tantamount to a betrayal of all natural principles?”

It might sound like Leibniz is talking about a resurgent interest in astrology, but he’s not. He’s talking about forces—in particular, Newton’s argument that forces can act at a distance. The idea that the planets are “gravitating and striving toward each other,” and that “matter is supposedly able to perceive and covet even things which are remote” is “fanciful,” Leibniz says.

Leibniz thought as little of Newton’s gravitational force as he did of astrology, which he dismissed as “pure nonsense.” That said, he was a great believer in the power of Biblical prophecy. “The prophets of the Old Testament have amazingly foreseen the detail of the new,” he once wrote to Sophia, Electress of Hanover. He firmly believed that the Jesuits embodied the locusts who rise out of the Abyss in the Book of Revelation. “This is something that should not be doubted unless one is a disciple of the Antichrist,” Leibniz says.

We find it easy to forgive Leibniz his biblical follies because of his valuable contributions to mathematics and science. We do the same for Newton, whose follies were arguably greater. And we should extend the same courtesy toward ancient astrologers.

I’m not ashamed to say that I have a soft spot for astrology. Historically, astrology is the grit that seeded the pearl; its data-gathering, map-making, and pattern-seeking laid the cognitive foundations for modern science. Rather than rudely dismiss it as an embarrassing product of ignorant times, we should acknowledge its contribution.

And astrology remains useful today. It provides a useful illustration of the vexatious fallibility of human intellectual achievement—including, and perhaps particularly, the sometimes illusory certainties of science. It’s certainly something to keep in mind as we make our modern maps of particles, forces, and strange cosmological energies. Who knows? Perhaps future generations will lump 21st-century interpretations of data together with those of the astrologers—a laudable but clumsy attempt to find meaning in the meaningless—and wonder why we learned nothing from the failings of the earliest attempts to understand the universe.

Michael Brooks holds a Ph.D. in physics, and is the author of The Quantum Astrologer’s Handbook.

Lead image: Pavel Malitskyi / Shutterstock