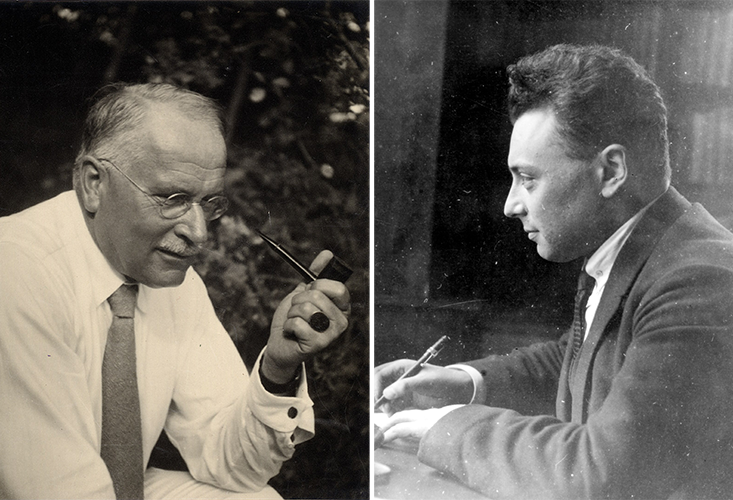

By the end of 1930, Austrian-born theoretical physicist Wolfgang Pauli was at the height of his achievements, yet an absolute emotional wreck. His brilliant contributions to science—such as the famous exclusion principle that would eventually earn him a Nobel Prize—had cemented his reputation as a genius. Remarkably, it demonstrated, among other consequences, why the electrons in an atom don’t all cluster together in the lowest energy quantum state and render it unstable. He had also predicted the existence of a lightweight, electrically neutral particle—later dubbed the neutrino—that, while yet to be found experimentally, already offered a way forward in understanding a radiative process called beta decay.

But while the particle world was starting to shape up nicely, Pauli’s own world was crashing around him. His cascade of troubles began three years earlier, when his beloved mother committed suicide, at the age of only 48, in reaction to his father’s infidelity. Within a year his father remarried, wedding an artist who was in her late 20s—around the same age as Pauli at the time. Pauli derided his father’s decision and nicknamed his father’s new wife “the evil stepmother.”

By then, while Pauli’s career was boosted by being appointed to a professorship at the ETH [Swiss Federal Institute of Technology] in Zurich, he had become increasingly disillusioned. For reasons not entirely understood, in May 1929 he abandoned the religion of his birth, Catholicism, by formally leaving the Church. Pauli traveled often to Berlin, where Einstein, Schrödinger, Planck (then emeritus, but still active), and other luminaries made it one of the major hubs of theoretical physics. During one of his visits to that city he met the cabaret dancer Käthe Deppner and began dating her. She had another boyfriend at the time, a chemist, but was open to Pauli’s interest. He proposed marriage to her, which for some reason she accepted, despite his being far from the man of her dreams. They wed in December 1929.

It was a troubled marriage from the start. Her interest in the chemist had not waned and she continued to see him. After a few weeks, she essentially ignored her husband. Pauli spent most of the next year in Zurich; she remained in Berlin. By November 1930 they were divorced. To Pauli’s chagrin, she ended up with the chemist. “Had she taken a bullfighter, I would have understood, but such an ordinary chemist …” he bemoaned.

With his emotional life in shambles, Pauli took up drinking and smoking heavily. He became a familiar presence at Mary’s Old Timers Bar, a Zurich tavern styled after American speakeasies. It is remarkable that his neutrino idea had emerged around the same time. He was focused enough to remain productive even with his life in crisis. Pauli’s father decided to intervene, suggesting that he seek out Carl Jung for therapy.

One of the remarkable aspects of the Pauli–Jung collaboration was how their rhetoric had begun to converge.

Pauli was familiar with Jung’s work, as he spoke often at the ETH. Agreeing to his father’s suggestion, Pauli contacted Jung and made an appointment. By that point, he was desperate to get his inner life back on track and hoped that therapy might make a difference. Pauli expected to be treated by the founder of analytical psychology himself, but Jung assigned him to his young assistant, Erna Rosenbaum. Jung explained that given Pauli’s issues with women he might best be analyzed at first by a female therapist. Her role was to write down Pauli’s dreams until he was confident enough to jot them down himself.

Rosenbaum’s treatment of Pauli began in February 1932 and lasted about five months. Then, Pauli was placed in the driver’s seat, noting his own dreams for about three months in a kind of self-analysis. Finally, Jung took over personally as his therapist for the following two years. Once Jung started treating Pauli directly, he already had more than 300 recorded dreams to analyze, greatly aiding him in shaping his therapeutic suggestions. In addition to sharing his dreams, Pauli opened up about his emotional turmoil, erratic behavior, alcohol dependency, and issues dealing with women.

For Jung’s studies of the impact of the collective unconscious on the psyche, including the roles of dreams and fantasies, he sought out subjects with vivid recall. His developing notion of synchronicity, based as it was on dynamic Einsteinian notions of space and time, could certainly benefit from a physicist’s voice. A prominent quantum physicist, who happened to have complex dreams he could remember with ease, was an extraordinary find.

Ultimately, either directly or indirectly, Jung compiled roughly 1,300 of Pauli’s dreams and would make use of them (while maintaining patient confidentiality) for his research studies. Consequently, as the scholar Beverley Zabriskie wryly points out, “Readers of … Jung are more familiar with Wolfgang Pauli’s unconscious than with his waking life and achievement.” It is a mystery how Pauli remembered so many dreams in such great detail. Truly, his recall was phenomenal, and he must have trained himself in some manner. The dreams added immensely to the resources Jung could draw upon in crafting his theories.

But of course, it wasn’t just a research project. Jung genuinely wanted to help Pauli become more aware of his stifled feelings. The gist of Jung’s treatment was to show Pauli how his emotional self, symbolized by the anima archetype, was repressed in favor of pure intellect. Pauli came to understand how his life was imbalanced. Gradually, over two years of therapy, he would become more settled—at least for a time. Finally able to maintain a mature relationship, in 1934 he married Franciska “Franca” Bertram in London. Around the same time, he decided to end his private therapy sessions. He was feeling more stable and had cut back—at least temporarily—on his drinking.

A prominent quantum physicist, who happened to have complex dreams, was an extraordinary find.

Though no longer a patient, Pauli would keep up his correspondence with Jung until almost the end of his life, including sharing his dreams. They’d continue to speculate together about their significance and connections to archetypes. With a brilliant mathematical mind engaged in unraveling the deepest questions in theoretical physics, it is not surprising that many of Pauli’s dreams had geometric elements and abstract symbols. They’d often include symmetric arrangements of circles and lines, which Jung would interpret in light of his notion of archetypes. As mathematical physics fed Pauli’s visions, which Jung connected with ancient symbolism, the two thinkers ended up weaving profound metaphorical connections between the two realms.

Pauli wrote to Jung reporting a dream he had about a physics congress with many participants. The dream had numerous images representing physical examples of polarization (separation of one thing into two opposites), including electric dipoles (balanced arrangements of positive and negative charges) and the splitting of atomic spectral lines within an applied magnetic field. Jung responded the dream symbolism likely represented “the complementary relationship in a self-regulating system [including] man and woman.”

A saying attributed to Freud is that “sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.” As a physicist, wouldn’t Pauli naturally sometimes have dreams with physics-related content? Couldn’t it be that “sometimes a dipole is just a dipole,” not a symbolic union of man and woman? Jung, like Freud, recognized that possibility and was generally careful not to be dogmatic in his conclusions.

Another of Pauli’s dreams included an ancient symbol called the Ouroboros: a serpent devouring its own tail while coiled into a circle. Such symbolism, related to the yin-yang icon of Taoism, reflects the concept of eternal destruction and rebirth, including the turning of the seasons and the recycling of the natural elements. Such a figure also displays the rotational symmetry that Pauli and others employed in their explorations of quantum properties. Drawing from a term in Eastern philosophy, it also forms a rudimentary kind of mandala.

One of the remarkable aspects of the Pauli–Jung collaboration was how their rhetoric had begun to converge. Thanks to Pauli, Jung had become far more knowledgeable about quantum physics, including its chance aspects and the role of observers. Thanks to Jung, Pauli had become immersed in the studies of mysticism, numerology, and ancient symbolism.

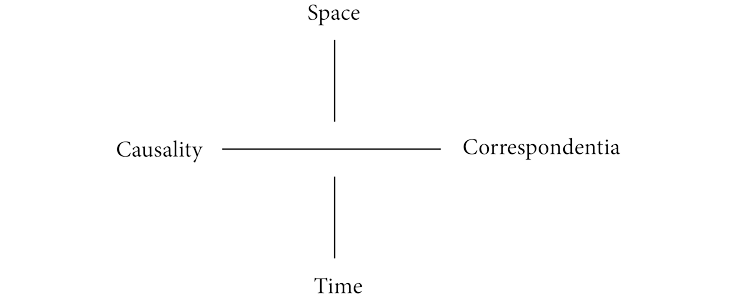

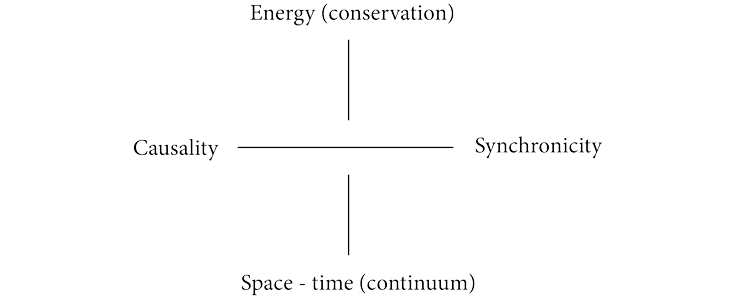

Around that time, Jung began to hone his notion of synchronicity in preparation for developing a treatise on the subject. With the help of Pauli, he hoped to shape it into a key principle acknowledged by the psychological community. As part of that goal, he aspired to develop his own emblem—a quaternio—as shorthand for how nature is connected. Jung would schedule a two-part series of talks on the subject. In preparation for the lectures, in 1950, he sent Pauli a letter that included a quaternio diagram that juxtaposed causality with correspondentia (a term referring to acausal connections analogous to the Hermetic law of correspondence) and space with time. It looked like:

On Nov. 24, 1950, after having a chance to think about Jung’s diagram, Pauli responded with a critique about his division of space and time into opposites. Einstein’s revolution, Pauli pointed out, merged space and time into a single entity—space-time—not opposites. Instead, he suggested a modified diagram (which Jung accepted with slight further modifications):

Pauli’s contrast of energy (and momentum) with space-time matched the dichotomy posed by the relativistic version of Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. The more that is known about space-time, the less that is known about energy-momentum (similarly a four-dimensional entity in relativity), and the converse.

Pauli’s concept of causality, called “statistical causality,” which Jung came to adopt as well, was distinct from mechanistic models. He argued that given the random outcomes in certain kinds of individual quantum measurements, such as determining whether or not a radioactive sample has exhibited a single decay within a certain time frame, the law of cause and effect needed to include the notions of chance and averaging.

The results of experiments are predictable only once the researchers take averages over many trials. In the same letter, Pauli connected synchronicity with parapsychologist J.B. Rhine’s mind-reading research: “As you yourself say, your work stands and falls with the Rhine experiments. I, too, am of the view that the empirical work behind the experiments is well-founded.”

Enthusiastic about Pauli’s suggestions, Jung responded with the bold proposal of generalizing synchronicity to include acausal relationships without a mental component—that is, purely physical interactions. He did not specify quantum entanglement, but surely that fell into Jung’s expanded definition.

“After thoroughly studying their writings for many months now, I have come to see clearly that they are both utterly mad.”

Ironically, his generalization served to decouple the concept of synchronicity from the Rhine results, precisely at the same time he and Pauli were embracing them. A broad definition of synchronicity as any acausal connecting principle encourages exploration of how the universe is intertwined through symmetry and additional mechanisms other than the chain of cause and effect. With some reservations, Pauli saw merit in Jung’s expanded definition. Any extension to physical processes, he emphasized, needs to move beyond psychological terms, such as archetypes, that would not be appropriate.

He wrote to Jung on Dec. 12, 1950: “[T]he more general question seems to be the one about the different types of holistic, acausal forms of orderedness in nature and the conditions surrounding their occurrence. This can either be spontaneous or ‘induced’—i.e., the result of an experiment devised and conducted by human beings.”

In 1952, as the culmination of their collaboration, Jung and Pauli published a joint volume, Naturerklärung und Psyche (The Interpretation of Nature and the Psyche). It included two treatises, “Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle,” by Jung, and “The Influence of Archetypal Ideas on the Scientific Ideas of Kepler.” Their combined work effectively outed (for anyone who read it closely) Pauli as the source of Jung’s dream material. Decades later, the first part (Jung’s section) would be released as a popular paperback. It contained Jung’s famous anecdote of the scarab, as an example of the “meaningful coincidence” he associated with synchronicity:

A young woman I was treating had, at a critical moment, a dream in which she was given a golden scarab. While she was telling me this dream, I sat with my back to the closed window. Suddenly I heard a noise behind me, like a gentle tapping. I turned round and saw a flying insect knocking against the window-pane from the outside. I opened the window and caught the creature in the air as it flew in. It was the nearest analogy to a golden scarab one finds in our latitudes, a scarabaeid beetle …

For scientific minds, such anecdotal evidence did not help Jung make his case. Any psychotherapist who has analyzed thousands of dreams by various patients would be bound by simple chance to note coincidences at some point between elements in dreams and common events in real life, such as encounters with insects. Indeed, Jung freely acknowledged that there were alternative explanations for each of the stories he told—he just wanted his readers to note a pattern. Greater emphasis on his generalized definition of synchronicity, which encompassed physical acausal connections (such as entanglement and symmetry relationships) would have made a stronger argument for the need to move beyond pure causality.

But as it stood, Jung’s combination of incidents, dreams, and mythology won over few scientific adherents, aside from Pauli. One review of the book, written anonymously by an eminent mathematician, concluded: “After thoroughly studying their writings for many months now, I have come to see clearly that they are both utterly mad.”

In August 1957, Pauli and Jung exchanged the final letters in their lengthy correspondence. Pauli’s note to Jung that month was one of his longest, including a long description of a dream and exposition about symmetries in physics. Jung responded with great interest to Pauli’s letter, interpreting the dream Pauli mentioned as symbolic of the reconciliation of opposites, such as psyche and body. Jung suggests that parity symmetry violation in the weak interaction is analogous to an arbiter—called the “Third”— taking sides between two otherwise symmetrically opposite entities. The Third might slightly favor psyche over body, breaking the symmetry between them. The rest of Jung’s note delved into his new interest in UFOs (Unidentified Flying Objects), which he had concluded are either real (from space) or a new kind of mythology with its own archetypes.

Why did Pauli and Jung’s lengthy correspondence end with that exchange of letters, even though Pauli lived for more than a year longer? A gap of months or even years sometimes happens even in the letter-writing of good friends. Moreover, as we’ve seen in his attitude toward other physicists, Pauli was in his heart a skeptic. He critically examined any dogma, including Jung’s. He complained to Bohr, for instance, about some of the vagaries of Jung’s approach: “The Jung school is more broad minded than Freud has been, but correspondingly less clear. Most unsatisfactory seems to me the emotional and vague use of the concept of ‘Psyche’ by Jung, which is not even logically self-consistent.” Pauli also began to cast doubt on Rhine’s methods. In a letter to Rhine, dated Feb. 25, 1957, but received only after his death, Pauli asked Rhine about an article he had heard about that was critical of parapsychology. Rattled by the letter, Rhine complained to Jung, who tried to track down the critical piece but found no evidence of its existence.

Further impetus for Pauli to disassociate from Jung was the latter’s obsession with UFOs. Pauli was curious about that question, but not enough to devote the time to it for which Jung might have hoped. That period corresponded to a major collaboration on unified field theory Pauli conducted with Heisenberg. Additionally, Pauli’s stamina began to decline in his final year before he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Thus a host of factors might have led to the end of the long, productive dialogue.

Paul Halpern, a professor of physics at the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia, is the author of Synchronicity: The Epic Quest to Understand the Quantum Nature of Cause and Effect. His other books include, most recently, The Quantum Labyrinth and Einstein’s Dice and Schrödinger’s Cat.

Excerpted from Synchronicity: The Epic Quest to Understand the Quantum Nature of Cause and Effect. Copyright © 2020 by Teasel Muir-Harmony. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Lead image: igor kisselev / Shutterstock