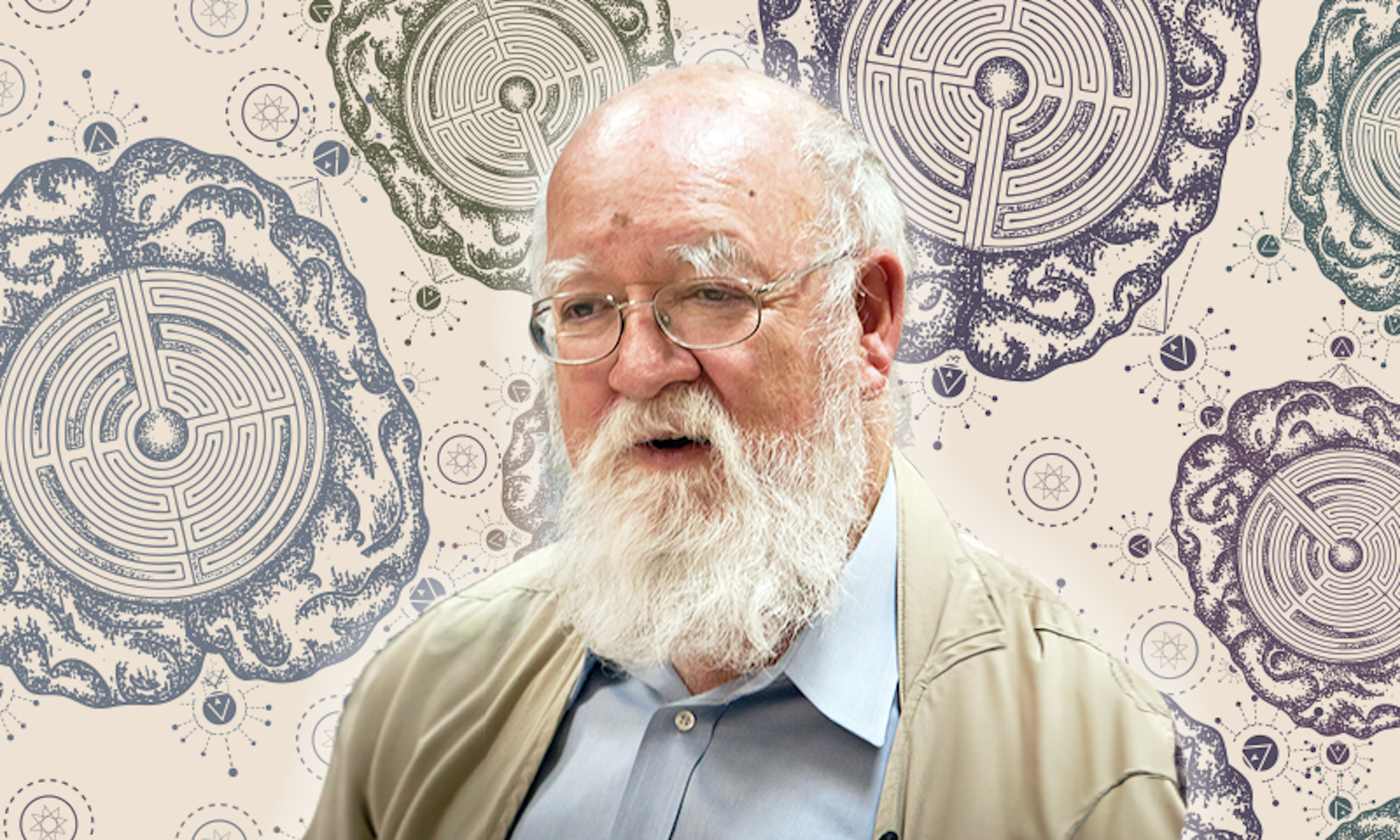

Daniel Dennett, who died in April at the age of 82, was a towering figure in the philosophy of mind. Known for his staunch physicalist stance, he argued that minds, like bodies, are the product of evolution. He believed that we are, in a sense, machines—but astoundingly complex ones, the result of millions of years of natural selection.

Dennett wrote more than a dozen books, some of them aimed at a scholarly audience but many of them directed squarely at the inquisitive non-specialist—including bestsellers like Consciousness Explained, Breaking the Spell, and Darwin’s Dangerous Idea. Reading his works, one gets the impression of a mind jammed to the rafters with ideas. As Richard Dawkins put it in a blurb for Dennett’s last book, a memoir titled I’ve Been Thinking: “How unfair for one man to be blessed with such a torrent of stimulating thoughts.”

Dennett spent decades puzzling over the existence of minds. How does non-thinking matter arrange itself into matter that can think, and even ponder its own existence? A long-time academic nemesis of Dennett’s, the philosopher David Chalmers, dubbed this the “Hard Problem” of consciousness. But Dennett felt this label needlessly turned a series of potentially-solvable problems into one giant unsolvable one: He was sure the so-called hard problem would evaporate once the various lesser (but still difficult) problems of understanding the brain’s mechanics were figured out.

Can we build from an account of rudimentary, strained aboutness all the way to human consciousness?

Because he viewed brains as miracle-free mechanisms, he saw no barrier to machine consciousness, at least in principle. Yet he had no fear of Terminator-style AI doomsday scenarios, either. (“The whole singularity stuff, that’s preposterous,” he once told an interviewer for The Guardian. “It distracts us from much more pressing problems.”)

As keen as the workings of his mind may have been, Dennett was among the least pretentious of scholars. As one journalist noted, he dressed “like a Maine fisherman”; for many years, he and his wife, Susan, spent their summers in a farmhouse a five-hour drive north of Boston. His passions extended beyond science and philosophy: He mastered at least five musical instruments—for a time he earned money as a jazz pianist—and, in spite of his avowed atheism, sang Christian hymns like “O Hearken Ye” like a practiced choirboy.

To give a sense of the breadth and depth of Dennett’s thinking, we have compiled here 10 snippets from his writings and from interviews he gave over the years.

The mind is a “user-illusion” that we mistake for reality

And what is this self? Not a dedicated portion of neural circuitry but rather like the end-user of an operating system. … Curiously, then, our first-person point of view of our own minds is not so different from our second-person point of view of others’ minds: We don’t see, or hear, or feel, the complicated neural machinery churning away in our brains but have to settle for an interpreted, digested version, a user-illusion that is so familiar to us that we take it not just for reality but also for the most indubitable and intimately known reality of all. That’s what it is like to be us. We learn about others from hearing or reading what they say to us, and that’s how we learn about ourselves as well. This is not a new idea, but keeps being rediscovered apparently. The great neurologist John Hughlings Jackson once said, “We speak, not only to tell others what we think, but to tell ourselves what we think.”

—From Bacteria to Bach and Back (2017)

Free will is a fantasy, but a welcome one

The traditional view of free will, as a personal power somehow isolated from physical causation, is both incoherent and unnecessary as a grounds for moral responsibility and meaning. The scientists and philosophers who declare free will a fiction or illusion are right; it is part of the user-illusion of the manifest image. That puts it in the same category with colors, opportunities, dollars, promises, and love (to take a few valuable examples from a large set of affordances). If free will is an illusion then so are they, and for the same reason. This is not an illusion we should want to dismantle or erase; it’s where we live, and we couldn’t live the way we do without it. But when these scientists and philosophers go on to claim that their “discovery” of this (benign) illusion has important implications for the law, for whether or not we are responsible for our actions and creations, their arguments evaporate.

—From Bacteria to Bach and Back (2017)

Consciousness runs on multiple parallel tracks at once

According to the Multiple Drafts model [of consciousness], all varieties of perception—indeed, all varieties of thought or mental activity—are accomplished in the brain by parallel, multitrack processes of interpretation and elaboration of sensory inputs. Information entering the nervous system is under continuous “editorial revision.” For instance, since your head moves a bit and your eyes move a lot, the images on your retinas swim about constantly, rather like the images of home movies taken by people who can’t keep the camera from jiggling. But that is not how it seems to us. People are often surprised to learn that under normal conditions, their eyes dart about in rapid saccades, about five quick fixations a second, and that this motion, like the motion of their heads, is edited out early in the processing from eyeball to … consciousness.

—Consciousness Explained (1991)

Darwinian evolution has extraordinary explanatory power

Let me lay my cards on the table. If I were to give an award for the single best idea anyone has ever had, I’d give it to Darwin, ahead of Newton and Einstein and everyone else. In a single stroke, the idea of evolution by natural selection unifies the realm of life, meaning, and purpose with the realm of space and time, cause and effect, mechanism and physical law. But it is not just a wonderful scientific idea. It is a dangerous idea. My admiration for Darwin’s magnificent idea is unbounded, but I, too, cherish many of the ideas and ideals that it seems to challenge, and want to protect them. … The only good way to do this—the only way that has a chance in the long run—is to cut through the smokescreens and look at the idea as unflinchingly, as dispassionately, as possible.

—Darwin’s Dangerous Idea (1995)

No miracles allowed

The two related philosophical problems I was trying to solve—at least in outline—can be rendered quite straightforwardly. First, how can it be that some complicated clumps of molecules can be properly described as having states or events that are about something, that have meaning or content? And second, how can it be that at least some of these complicated clumps of molecules are conscious—that is, aware that they are gifted with states or events that are about something? You and I have thoughts and ideas and hopes and fears and we know that we do, and we can tell others about them. How is that possible? … Can we build from an account of rudimentary, strained aboutness all the way to human consciousness? That is the task that any physicalistic or materialistic theory of the mind must execute. No miracles allowed.

—I’ve Been Thinking (2023)

Cultural evolution can mimic biological evolution

The concept of cultural replicators—items that are copied over and over—has been given a name by Richard Dawkins, who proposed [in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene] to call them memes, a term that has recently been the focus of controversy. For the moment, I want to make a point that should be uncontroversial: Cultural transmission can sometimes mimic genetic transmission, permitting competing variants to be copied at different rates, resulting in gradual revisions in features of those cultural items, and these revisions have no deliberate, fore-sighted authors. The most obvious, and well-researched, examples are natural languages. The Romance languages—French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and a few other variants—all descend from Latin, preserving many of the basic features while revising others. Are these revisions adaptations? That is, are they in any sense improvements over their Latin ancestors in their environments? There is much to be said on this topic, and the “obvious” points tend to be simplistic and wrong, but at least this much is clear: Once a shift starts to emerge in one locality, it generally behooves local people to go along with it, if they want to be understood.

—Breaking the Spell (2006)

Religion doesn’t need to be abolished—merely fixed

Does religion “poison everything,” as my dear, late friend Hitch [Christopher Hitchens] insisted on saying? Only in a very attenuated sense, I think. Many things are quite harmless in moderation and poisonous only in quantity. I understand why Hitch emphasized this view; as a foreign correspondent he had much first-hand, dangerous experience with the worst features of religion, while I know of all that only at second hand—often from his reportage. I, in contrast, have known people whose lives would be desolate and friendless if it weren’t for the non-judgemental welcome they have received in one religious organization or another. I regret the residual irrationalism valorized by almost all religion, but I don’t see the state playing the succoring, comforting role well, so until we find secular successor organizations to take up that humane task, I am not in favor of ushering churches off the scene. I would rather assist in transforming these organizations into forms that are not caught in the trap of irrational—and necessarily insincere—allegiance to patent nonsense.

—“Letting the Neighbours Know,” a chapter in The Four Horsemen: The Conversation that Sparked an Atheist Revolution (2019)

Behavior is predictable

Here is how it works: First you decide to treat the object whose behavior is to be predicted as a rational agent; then you figure out what beliefs that agent ought to have, given its place in the world and its purpose. Then you figure out what desires it ought to have, on the same considerations, and finally you predict that this rational agent will act to further its goals in the light of its beliefs. A little practical reasoning from the chosen set of beliefs and desires will in most instances yield a decision about what the agent ought to do; that is what you predict the agent will do.

—The Intentional Stance (1987)

The truth really does matter

The real danger that’s facing us is we’ve lost respect for truth and facts. People have discovered that it’s much easier to destroy reputations for credibility than it is to maintain them. It doesn’t matter how good your facts are, somebody else can spread the rumor that you’re fake news. We’re entering a period of epistemological murk and uncertainty that we’ve not experienced since the middle ages.

—The Guardian, Feb. 12, 2017

Reality is more magical than miracles

Some people don’t want magic tricks explained to them. I’m not that person. When I see a magic trick, I want to see how it’s done. People want free will or consciousness, life itself, to be real magic. What I want to show people is, look, the magic of life as evolved, the magic of brains as evolving in between our own ears, that’s thrilling! It’s affirming. You don’t need miracles. You just need to understand the world the way it really is, and it’s unbelievably wonderful. We’re so lucky to be alive! The anxiety that people feel about giving up the traditional magical options, I take that very seriously. I can feel that anxiety. But the more I understood about the things I didn’t understand, the more the anxiety ebbed. The more the joy, the wondrousness came back.

—Interview in the New York Times Magazine, Aug. 27, 2023 ![]()

Lead image: Tasnuva Elahi; with images by Dmitry Rozhkov / Wikimedia Commons and intueri / Shutterstock