This article is part of series of Nautilus interviews with artists, you can read the rest here.

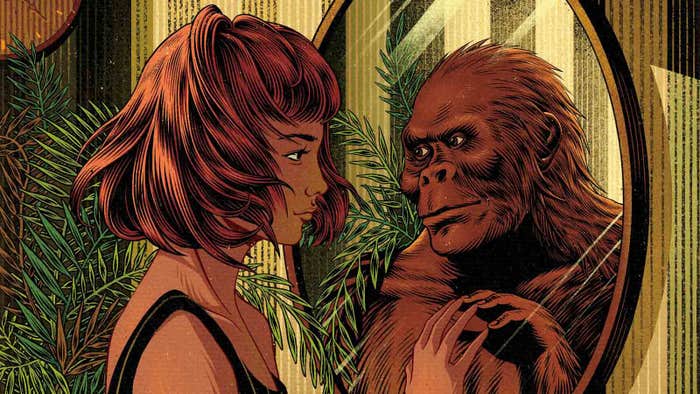

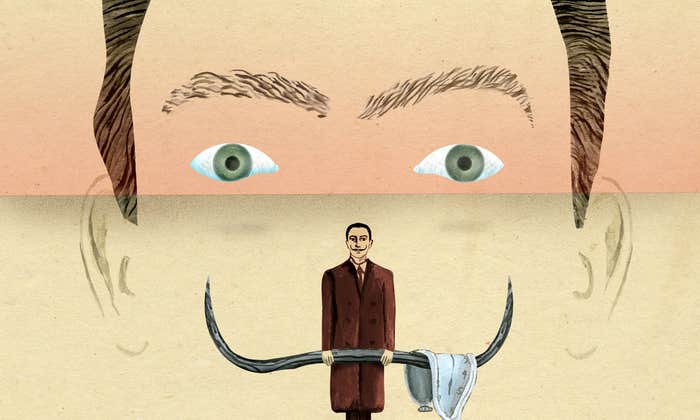

Award-winning illustrator Deena So’Oteh is a master of shadow and light. Her work, which has appeared in the pages of The Guardian, The New York Times, and Nautilus, often features luminous figures emerging from a foreboding darkness. In many ways, she says, the struggle between the two mirrors her own artistic journey. So’Oteh recently sat down to answer our questions about her journey to art, how she resolves creative blocks, and what scientists can learn from artists.

How did you decide pursuing art was the path you wanted to take?

My story might not be the typical one—I wasn’t the kid who always drew to escape into an imaginary world. In a way, the decision to pursue art was made for me, and once it was, there wasn’t much room for imagining other paths. My mom recognized an artistic inclination in me from an early age, so she made it a priority to nurture it. For much of my life, I assumed I would become a fine artist without ever questioning it.

My conscious decision to pursue art as a career came much later, and it was a more practical, grounded choice. My family immigrated to the United States when I was 12, and things took a rough turn. My parents went through a difficult divorce, and my father took away all our legal documents. By 18, instead of attending Parsons on a full scholarship, I found myself waitressing for the next eight years, thinking my only career path might be as a professional waitress.

When my legal status finally changed, I chose to pursue what I knew best—art—but not fine art as I had originally imagined. After eight years of uncertainty as an undocumented immigrant, I was seeking stability while doing something I loved. Illustration felt like a more practical use of my skills and a reliable way to make a living (little did I know!). I went on to earn a BFA in Illustration, but it wasn’t until my time at the School of Visual Arts for my master’s program that I realized my seemingly pragmatic decision was actually driven by something deeper and more intuitive. Illustration turned out to be the perfect fit for me. It combined everything I loved—reading, storytelling, learning, problem-solving, and creating—and opened doors to growth I hadn’t expected. It felt like I was finally on the path that was truly mine, and in a way, one that would make my mom even more proud.

Can you walk us through your creative process?

Unless I have an immediate response to a brief or a tight deadline, my process usually begins with a walk or another unrelated activity. From what I’ve learned from countless interviews with neuroscientists (which I often listen to while working), most of our neurons are wired for movement and I’ve found that moving around helps me process and rethink the material, giving me a fresh perspective—and it clears my head, too.

If I have the luxury of time (which, given the rise of AI, is becoming more rare), I let a day pass before revisiting the brief in the evening, highlighting words or phrases that spark visual ideas. To avoid distractions, I usually start sketching early—sometimes as early as 4 or 5 a.m. That quiet time, before the world wakes up, is when I feel most creative and free from the distractions of the day. I believe there’s a specific time that works best for each part of the creative process, and once you recognize it, the results can be much more productive.

I tend to think in color right away because it helps set the tone for the piece. I also make my sketches as large as the final artwork, as I’ve found that the serendipity of the sketch process often leads to discoveries I might want to keep in the final piece. Once the concept is approved, I give myself space to experiment with different brushes, textures, and techniques. This element of play and discovery is key to my creative process, as it keeps things exciting and fresh.

How do you work through a creative block?

When I hit a creative block, I often switch to another project that’s at a different stage or one where I feel a sense of ease. This helps relieve the pressure and creates the space I need to process the material. I believe creative blocks stem from not being in the right mental space, so my first priority is to reset. Sometimes, it’s personal life creeping in, and I have to acknowledge it and use it to fuel the creative process. Other times, it’s the stress of not knowing a topic well enough or worrying about how my work will be received. In those moments, I try to let go of my ego and imagined judgments, allowing the ideas to flow without the fear of failure.

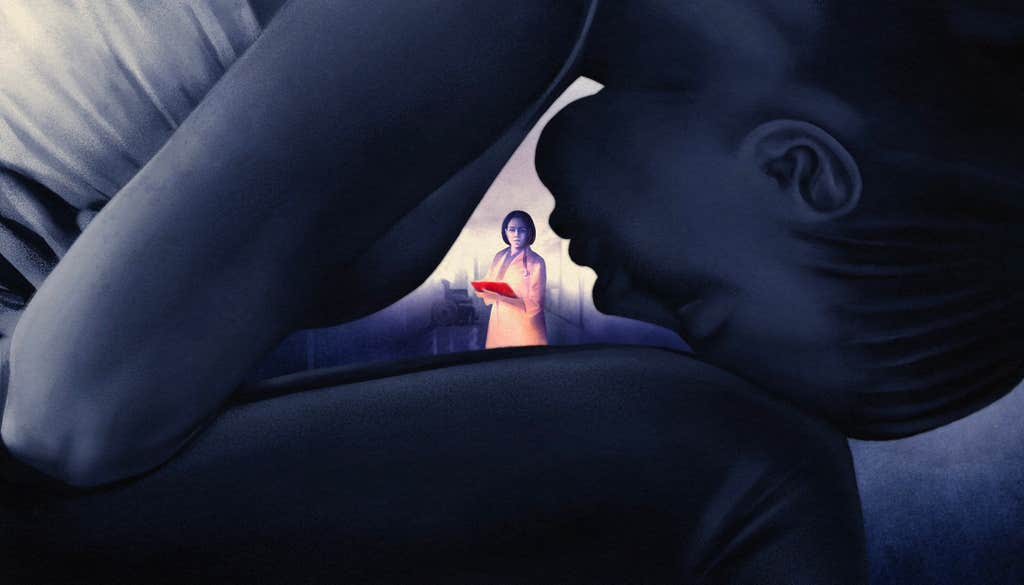

A lot of your work features bright lights and dark shadows. What attracts you to that aesthetic?

Artist Marshall Arisman always said, “Draw what you know.” It took me a while to understand what that meant for me personally, but over time it became clear: I know the internal struggle between light and dark.

I’ve been through some very dark periods in my life, and without my deep belief that there’s beauty beyond the struggles, my path might have been very different—and likely much shorter. Light and dark, in that sense, aren’t just visual contrasts; they represent the forces that shape our emotional and psychological journeys. They are always present, and we’re constantly trying to balance them within ourselves and in our lives.

So, it’s not that I’m particularly drawn to the aesthetic of light and shadow—rather, it’s more about the need to express what’s happening internally. This is how I process and understand my experiences. It’s a way to navigate and make sense of the complexities of life, using visual elements to reflect those ongoing, internal dialogues.

You created the art for the cover story of Nautilus Issue 48, “What Plants Are Saying About Us,” about the possibility of plant cognition. What about that story captured your imagination?

I’m totally fascinated by the natural world, cognition, and neuroscience. If I weren’t an artist, I think I’d be a scientist. I’ve always felt plants have a kind of intelligence, just not the kind we recognize. You can see it in how they adapt and respond, even if you keep their environment constant. This project was a chance to express that love for plants visually—a rare opportunity for me with this subject matter.

Is there anything you think scientists can learn from artists—or vice versa?

I believe, in essence, we are the same. Scientists are artists, and artists are scientists. Both fields require creative thinking to discover or perceive something new, as well as a deep understanding of materials and techniques. Whether it’s experimenting with new ideas or refining existing ones, both require a willingness to explore until that “Aha!” moment occurs. The divide between the two fields is much smaller than we often imagine. Sharing our approaches to thinking, analyzing, and processing information would benefit both scientists and artists, fostering greater collaboration and innovation across disciplines.

You recently illustrated your first children’s book, Narwhal, Unicorn of the Arctic. Did you approach that differently than your other illustration work?

With nonfiction, research is the first step in the creative process. I had to fully immerse myself in the world of narwhals before mapping out the book’s flow and beginning the sketches. It required a unique focus—honoring the natural world while making it accessible and engaging for children.

Creating a book also demands a different kind of stamina. I’m more of a sprinter by nature, and a book project is a marathon. That was a big learning curve for me. In editorial work, things move quickly; you’re a coiled spring, committing immediately to a composition, color palette, approach. A book, however, allows more time for experimentation, but also invites more self-doubt. There’s also the weight of knowing the book will live on someone’s shelf for years, adding both pressure and meaning to the process.

You created the cover art for an issue of The Guardian Weekly about the AI debate. What are your thoughts on the use of AI to create art?

AI is a complex and loaded topic, especially in the creative field. While some argue that AI is “just a tool,” it erases the years of personal effort, trial and error, and soul-searching that go into art. It risks devaluing the creative process.

We’ve adapted to tools like Photoshop, but AI feels different. It suggests that the years spent developing a unique artistic voice and honing one’s craft are no longer valuable, since anyone can now input a prompt and generate a similar result. While some argue that prompting AI itself is a form of art, I’d rather invest my time in learning to ask myself the right questions to create better and live a happier life than spend time teaching a machine.

Ultimately, the images AI generates shape our collective perceptions and influence how the next generation views art. Personally, I’d much prefer AI take over my laundry and house chores than solve my creative challenges.

Do you see any role for AI in your work?

Not within my artistic practice. If anything, AI makes me want to step away from digital work entirely and lean back into traditional methods, where the authenticity feels more tangible. Some people use AI as a reference and then recreate the image by hand, but for me, the whole point is in the process itself—the thinking, experimenting, and reflecting that goes into each piece. My work is craft, and it brings meaning to my life, defining my purpose and even my happiness. I want to apply it with respect and care, not rush or automate it.

Art, for me, is a kind of therapy. It’s a way to learn about myself, and that’s something I’m not interested in handing over to AI.

Interview by Jake Currie.

Lead image courtesy of Deena So’Oteh.