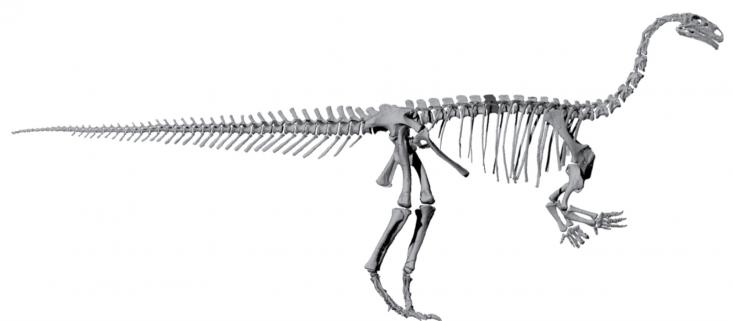

In 1898, the American Museum of Natural History was presented with a golden opportunity along with a challenge almost as significant. Paleontologist Walter Granger had returned from a trip to the West with an amazing find: a large set of fossilized bones from a 30-foot-tall, 80-foot-long dinosaur. (At the time the sauropod was known as Brontosaurus but later came to more accurately be called Apatosaurus.) The challenge was what to do with it.

The museum preparators and exhibitors had to improvise. They devised a frame of “repurposed pipes and plumbing fixtures” to support the structure. The skeleton Granger found was incomplete, so the museum created a composite of four different specimens, including the skull from a different kind of dinosaur. The process took more than six years. In 1905 Granger’s Apatosaurus became the first mounted sauropod dinosaur on display in the world.

Today museum preparators and exhibitors have successfully met most of the challenges posed by displaying such massive fossils, but they use essentially the same techniques as those at the end of the 19th century. Some experts say that paleontological collections are poised to undergo a revolution—one that might transform how fossils are viewed, studied, and re-created.

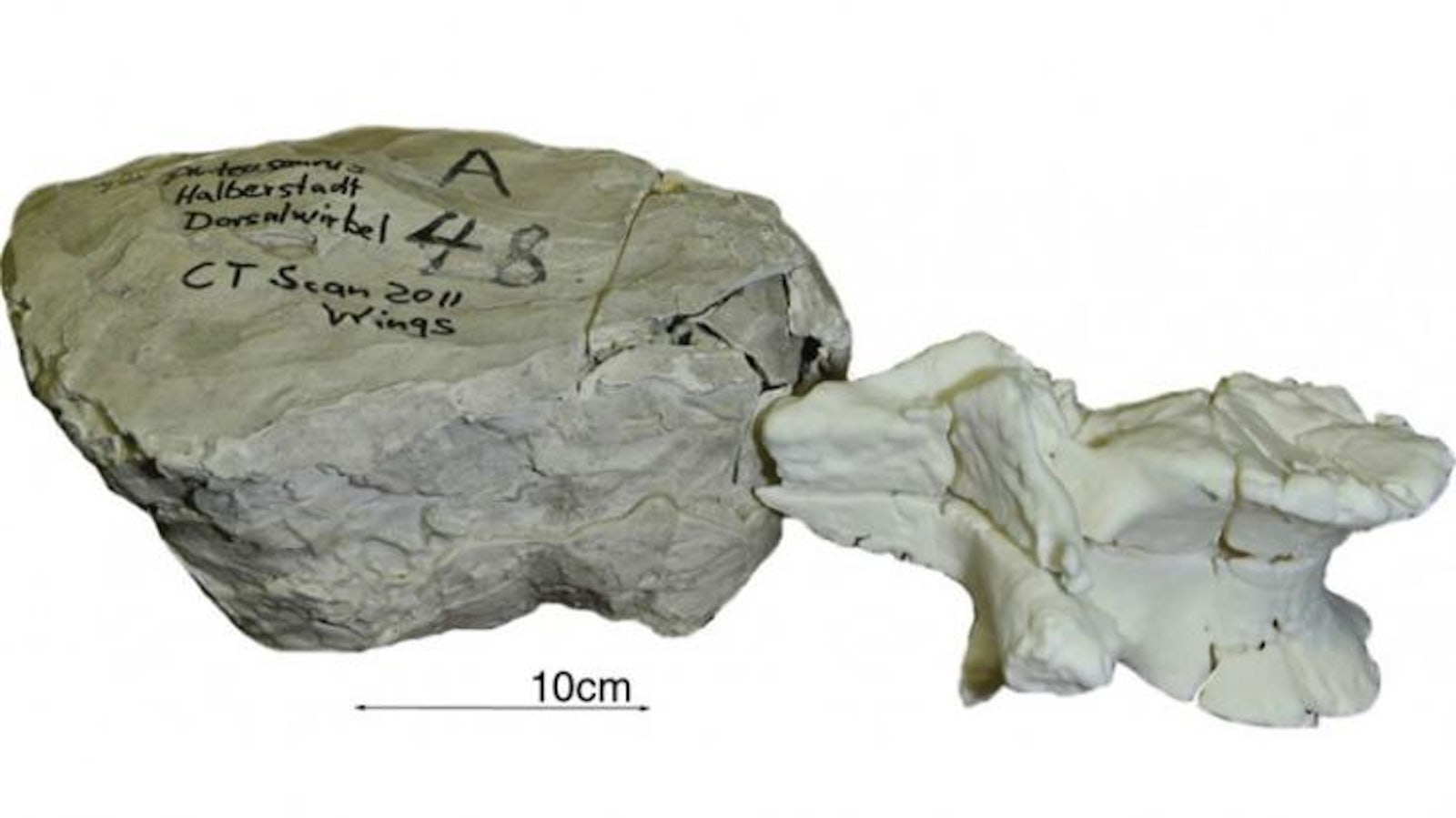

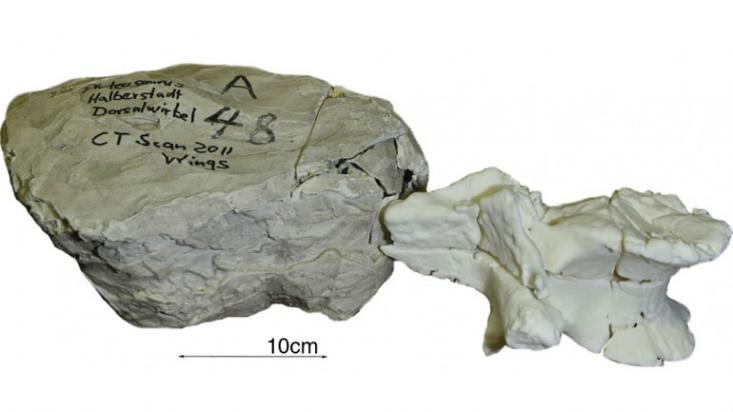

In an article published in the journal Radiology last fall, researchers affiliated with the Natural History Museum in Berlin announced that they had made an accurate copy of a fossilized dinosaur bone through a combination of three-dimensional imaging and three-dimensional printing technology. The sample had been buried in rubble in the basement of the museum during a bombing raid in WWII. Using the scans, the researchers showed that it had been mislabeled and in fact contained a vertebra from a member of the genus Plateosaurus—all without so much as opening the field jacket. “Just like Gutenberg’s printing press opened the world of books to the public, digital datasets and 3D prints of fossils may now be distributed more broadly, while protecting the original intact fossil,” said study author Dr. Ahi Issever, a radiologist at Charité Campus Mitte in Berlin, in a statement.

Though three-dimensional-imaging technology has been available since 1979, sharing fossil data among museums has, for the most part, remained the same since Granger’s day. When fossils were collected from the field, they were usually protected in “field jackets” made of plaster. Back at a museum, preparators labored to remove the plaster and sediment without disturbing the fossil, an extraction process that could take months to complete. Museum preparators then applied a flexible material like rubber to fossils to make molds of them. The molds were then separated from the fossils and filled with plaster to create casts, reproductions of the fossils that could be shared with other paleontologists. But plaster was heavy and didn’t capture surface detail very well. Worse yet, the molding material sometimes seeped into tiny cracks in the bone; when the molds were ripped off, the surface of the fossil sometimes would be ripped off too.

In the 1960s and ’70s, preparators began to make molds out of silicone instead of rubber and casts out of polyester resin, a common plastic, instead of plaster. These new materials allowed for greater structural detail, but were, essentially, the same approach.

Over the past decade or so, museums have slowly started adopting new technologies to create non-invasive reproductions, specifically by doing three-dimensional imaging. For the most part, these researchers are using X-ray computed tomographic (CT) scanning, a technique used widely in medicine. Medical CT scanners work well for the human body, but there are also industrial scanners that generate much more powerful X-rays to penetrate denser materials, such as rocks and fossilized bones. CT scans capture two-dimensional X-ray images as cross-sections of the scanned objects; the images are then reassembled in a digital program to create a three-dimensional image. Molding and casting requires a lot of material, time, and labor. Creating molds, particularly for a big specimen, can take months. The same process can now be achieved by using CT scanning in much less time. In addition, specimens don’t have to be disassembled from their field jackets.

“If you can compress months into minutes, that’s awesome—[considering the] time wasted and money wasted and materials wasted,” says Carl Mehling, senior scientific assistant at the American Museum of Natural History. “And, most important from my perspective, it seems in every respect to be completely harmless to the specimen. You’re not touching it. You’re not adhering anything that you’re going to pull off later, and the specimen may fail and stick to it. And that data seemingly also won’t degrade over time.”

“What is a thing? If you can replicate it down to the molecules and atoms, is that thing identical? Is it the same thing or is it a different thing?”

Despite the benefits, scanning seems slow to catch on, according to Mehling. To date, the American Museum of Natural History hasn’t made scanning the fossil record a priority. “We’re in the paradigm shift right now,” Mehling says. To some degree, it’s an issue of control. If another museum or a wealthy collector got access to detailed scans of a dinosaur, they could,like the researchers in Berlin, and print out an accurate, 3D copy. And with the ongoing boom in 3D-printing technology, the replicas will likely get better, bigger, and cheaper. “The way the rules are, if somebody requests a cast, we kind of have control over how it’s used and who has it and what is done with it. Because we consider it part of our intellectual property,” he says.

The Smithsonian Institution is facing a similar problem, according to Steve Jabo, a preparator there. “We generally treat the data like an actual specimen. But it’s different because it’s all on the computer and it’s easy to replicate, easy to pass around…. We have to get a real solid white-paper policy on digital data.”

In Mehling’s view, scanning and printing have the potential to alter museum collections as we know them. “This is really hard to imagine,” he says with a laugh. “But I sometimes wonder if collections may even disappear if scanning becomes so phenomenally detailed . . . What is a thing? If you can replicate it down to the molecules and atoms, is that thing identical? Is it the same thing or is it a different thing?”

Granger’s Apatosaurus is still towering over visitors in the Dinosaur Wing of the American Museum of Natural History, with a few modifications from the century it has been there to make it more accurate. It seems unlikely that a digital representation, or even a 3D facsimile, could recreate the awe-inspiring feeling of standing under a 150-million-year-old dinosaur.

Katie Jennings (@ktjenwords on Twitter) is a freelance health and science writer based in Brooklyn, NY.