Opioid addiction can be seen as an infinite loop, a bug in the brain’s programming. Take drug. Feel better. Come down. Repeat.

Of the people who use opioid drugs recreationally, between 8 and 23 percent become addicted—sometimes fatally. That’s true whether the opioid drug is strictly prohibited, such as heroin, or a prescription painkiller that people use illegally, such as OxyContin or Vicodin. A smaller proportion of people who take prescription painkillers get hooked—less than 1 percent of people with no prior history of addiction.

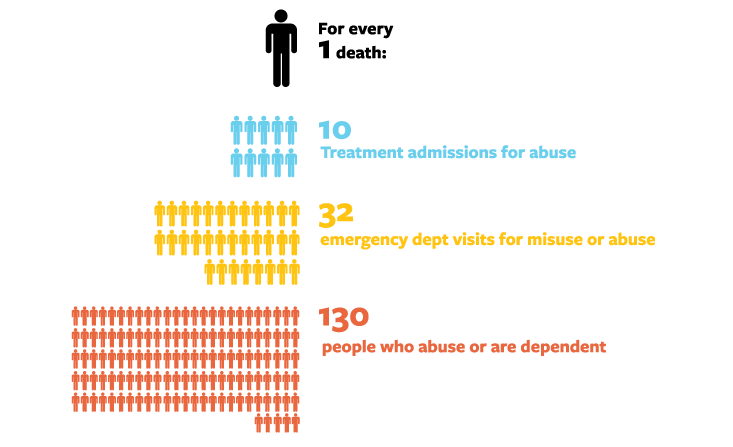

In the United States, the world’s largest consumer of all types of drugs, these numbers add up: More than 2 million people are currently addicted to opioids, and nearly 5 million have taken them recreationally in the past month and may be at risk. Consequently, scientists have been searching for a “non-addictive opioid” since the 1800s—desperately seeking a compound that can match these drugs’ peerless pain relief without becoming irresistible.

Some elements of the addictive loop are well understood. The primary factor being that the drugs feel alluring, dreamy, and blissful to a fraction of the people who take them. Meanwhile, about 15 percent strongly dislike them, according to research on healthy volunteers.1

“Some people get nauseated,” says Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. “They hate it.” (Dan Rather, who was given a shot of heroin by police during a bit of method-style reporting for a Houston broadcast station in the 1950s, said he never wanted to repeat it and that the drug gave him a “hell of a headache.”)

In the same study, about half of the participants found the opioid experience to be mixed: not entirely pleasant or unpleasant, or simply neutral.

But around 30 percent of people find opioids euphoric, and they are at the highest risk of addiction. Interestingly, within this group about half immediately say: “That was so good. I better stay away.” The rest, however, continue to seek something like the feeling of “kissing God,” which is how comedian Lenny Bruce described the heroin high.

So, the first step in the loop is liking the drug—or at least finding that it eases emotional problems. Synthetic opioids do, after all, act on the receptors for the brain’s natural opioids, the endorphins and enkephalins, which are neurotransmitters that relieve stress by making you feel warm, safe, fed, and loved. If you are troubled—especially if you had a traumatic childhood and have always been troubled—these drugs may feel particularly liberating. And every time you take them, the brain reinforces the connection between drugs and life’s fundamental comforts.

Unfortunately for addicted people, another feedback loop starts here: When opioid levels get too high, other neurochemical systems jump in and balance out the brain’s response. “You become tolerant to them very rapidly,” Volkow says.

As time goes by, more of the drug is needed to get the same effect, and this causes physical dependence. Now you need opioids simply to feel normal; without them, you lose your means of coping with your emotions and you suffer withdrawal symptoms. This closes the loop, skewing decision-making systems to prioritize drug seeking, despite the negative consequences that often occur.

Pharmaceutical researchers have tried to interrupt stages in this cycle for as long as drug companies have existed. In 1898, Bayer synthesized heroin from the opium poppy. The name comes from “heroic”—heroin was believed to be not only a stronger painkiller than morphine, but also less addictive.

The pattern has continued ever since. “Almost immediately when pharmaceutical companies started introducing products, they claimed they were either non-addictive or less addictive,” says David Herzberg, a historian at the University at Buffalo, The State University of New York. Then this claim would turn out to be false, or at least overstated.

In 1898, Bayer synthesized heroin from the opium poppy. The name comes from “heroic.”

In 1915, for example, Roche introduced a drug called Pantopon, which was also made from the opium poppy. It was said to be less addictive than morphine because it contained multiple compounds from the plant, which was supposed to be safer because it was more “natural.” It wasn’t.

In the 1930s, a drug called desomorphine was the new non-addictive analgesic. It was simply another opioid—and therefore addictive. (It’s now infamous in Russia under the name “Krokodil” for the grotesquely disfiguring skin condition caused by the impure drug. Botched illegal manufacture is common in Russia, in part because opioids are so hard to get there.)

In 1996, OxyContin was introduced as a less addictive opioid, with tragic results. By 2007, the number of overdose deaths from prescription opioids outnumbered deaths from heroin and cocaine combined.

Can we break the cycle? Several approaches offer some hope. Research has found repeatedly that the longer a drug lasts and the slower it is to reach the brain, the less addictive it is; a short, intense high produces more compulsive behavior.

In fact, the basis for the initial claim about OxyContin’s reduced addiction potential wasn’t actually wrong: The drug was a long-acting medication that was delivered slowly and steadily to the brain.

Unfortunately, recreational users almost immediately figured out how to defeat its time-release mechanism by crushing the pills, which then delivered a quick, massive dose when snorted, eaten, or injected. A wave of addiction and overdose death followed.

The manufacturer reformulated the drug using a potentially nasty trick: adding a substance called an opioid antagonist or blocker that, if snorted or injected, can block the high and even produce withdrawal symptoms like nausea, sweating, diarrhea, and vomiting. This version failed clinical trials because sometimes oral dosing unleashed the antagonist, which could punish pain patients who were using the drug as prescribed. (Other opioids sold today do use this mechanism, however, including Suboxone, a drug used to treat both pain and addiction.)

The current version of OxyContin has a different mechanism to reduce misuse. It contains substances that turn it into a gel if people try to dissolve it, which makes the drug almost impossible to get into a syringe. The tablets are also far more difficult to grind up small enough to defeat the time-release mechanism by snorting or swallowing a crushed pill.

“The evidence looks like it’s working,” says Volkow. One study found that addicted people unanimously preferred the older version and that the percentage of addiction treatment patients whose drug of choice was OxyContin fell from 36 percent to 13 percent after the new version was introduced.2

Several pharmaceutical companies have drugs in early human trials based on the principle that slower entry into the brain reduces addiction risk. New versions of oxycodone (the opioid in OxyContin) and hydrocodone (in Vicodin), for instance, are attached to molecules that prevent them from having any effect unless they first pass through the digestive system.

Other new approaches are more radical, and they stem from a growing body of knowledge about the specific proteins involved in the so-called addiction feedback loop. These drugs seek to break the addiction cycle before it starts, either by preventing the development of tolerance and dependence or by reducing the connection between pain relief and euphoria.

A drug called plus-naltrexone acts more specifically than existing opioid blockers, just on immune cells in the brain. When opioid drugs activate receptors called TLR4 on these immune cells, they cause inflammation that can exacerbate the pain that painkillers are meant to relieve. In addition, activated TLR4 receptors increase pleasure because they send signals that stimulate pleasure-related nerve cells, too. Therefore, by blocking TLR4, plus-naltrexone reduces overall pain, reducing the need for more and more drugs, and simultaneously lowering the “high.”

“If you give [plus-naltrexone] with morphine, the analgesia is much better,” says Linda Watkins, a psychologist at the University of Colorado at Boulder. She adds that at the same time, the animals it’s been tested on don’t “experience and associate it with reward.”

Another approach is to use compounds that simultaneously activate a pain-relief receptor called mu while blocking one that seems to modulate its effect, called delta.

One such medication, UMB 425, is being developed by Andrew Coop, a pharmaceutical scientist at the University of Maryland, and his colleagues. In rodent tests, it’s as potent as morphine, and maintains its effects even after the animal receives repeated doses. According to Coop, the drug probably works because it blocks delta, which prevents the receptor from adjusting to high levels of mu activation, leading to tolerance.

But there’s a snag in all of these commendable approaches. They will only help the minority of people who become addicted through pain treatment. Meanwhile, they’ll do little to aid the 80 percent of people who get opioids outside of the doctor’s office.

The OxyContin disaster teaches us hard lessons. The new formulation, introduced in 2010, has dramatically reduced OxyContin misuse—studies by the manufacturer found a drop of 40 to 50 percent in reports of misuse and a 70 percent decline in overdose deaths.3 But unfortunately, this hasn’t dented America’s overall opioid problem.

The percentage of Americans who suffered from prescription opioid addiction within a year of being surveyed has risen dramatically—from 0.6 percent in 2002 to 0.8 percent in 2012, while the proportion with heroin addiction rose from 0.1 percent to 0.2 percent in that same period.

What’s more, the reformulation of OxyContin didn’t stop people from becoming hooked. Instead, it seems to have driven them to other drugs, typically more dangerous street drugs. Overdoses linked to OxyContin fell 36 percent after 2010, but other types of oxycodone overdose rose by 20 percent and heroin reports skyrocketed by 42 percent.4

The quest to end addiction via non-addictive painkillers has failed time and time again because people are blaming drugs alone for the problem. Addiction is a relationship between a person and a drug: It either emerges or it doesn’t depending on one’s emotional coping skills, culture, developmental trajectory, options for satisfying work and relationships, and then, yes, available drugs. Regulators can’t stop it by simply controlling supplies of particular drugs—that only moves the craving elsewhere.

While non-addictive opioids could be extremely useful in eliminating or at least reducing addiction risk for some pain patients, they will fail to break the cycle in most people with addiction issues because they don’t intervene where the problem starts—inside someone who is suffering and doesn’t have other ways to manage distress.

At least 50 percent of opioid addicts have a co-existing and usually pre-existing psychiatric disorder, such as anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder. They are typically self-medicating these problems. The more childhood loss and trauma someone has experienced, the higher the risk of addiction. One study found that boys who experienced six or more childhood traumas such as abuse, neglect, or parental loss had a 46 times greater risk of becoming an intravenous drug user than those whose childhoods were not marked by violence or tragedy.5 Unemployment and lack of economic opportunity also add to the risk.

As long as troubled children and adults continue to lack the education, opportunity, support, and psychiatric care they need, the cycle of addiction will remain a problem in the U.S.—no matter how much money is funneled into a quest for the perfect drug.

Maia Szalavitz is a neuroscience journalist who covers addiction, love, and other topics related to the brain and behaviors for Time magazine, The New York Times, and the Washington Post, among other outlets.

References

1. Angst, M.S., et al. Aversive and reinforcing opioid effects: a pharmacogenomic twin study. Anesthesiology 117 (1), 22-37 (2012).

2. Cicero, T.J., Ellis, M.S., & Surratt, H.M. Effect of abuse-deterrent formulation of OxyContin. The New England Journal of Medicine 367, 187-189 (2012).

3. Cashin-Garbutt, A. Reformulated OxyContin: an interview with Dr. Paul Coplan, executive director, risk management and epidemiology, Purdue Pharma. News Medical (2013).

4. Coplan, P.M., Kale, H., Sandstrom, L., Landau, C., & Chilcoat, H.D. Changes in oxycodone and heroin exposures in the National Poison Data System after introduction of extended-release oxycodone with abuse-deterrent characteristics. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Safety 22 (12), 1274-1282 (2013).

5. Felitti, V.J. The relationship of adverse childhood experiences to adult health: turning gold into lead. Z psychsom Med Psychother 48 (4), 359-369 (2002).