“What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence.”

—Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951), Proposition 7 of Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

“After all, Mr. Wittgenstein manages to say a good deal about what cannot be said.”

—Bertrand Russell (1872–1970), introduction to Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

“Half the lies they tell about me aren’t true.”

—Yogi Berra

Rather than jumping headfirst into the limitations of reason, let us start by just getting our toes wet and examining the limitations of language. Language is a tool used to describe the world in which we live. However, don’t confuse the map with the territory! There is one major difference between the world we live in and language: Whereas the real world is free of contradictions, the man-made linguistic descriptions of that world can have contradictions.

In the first section, we encounter the famous liar paradox and its many variants. These are relatively easy puzzles that will get us started. The following section contains a collection of self-referential paradoxes. I show that they all have the same form. Then, in the last section, we meet several paradoxes involving descriptions of numbers.

Liar! Liar!

A linguistic paradox is a phrase or sentence that contradicts itself. A baby version of a linguistic paradox is an oxymoron (from the Greek oxys “sharp” and moros “stupid”—together they mean “pointedly foolish” or “pointedly dull”). These are phrases, usually consisting of two words, that contradict each other. Some examples are “original copies,” “open secret,” “clearly confused,” “militant pacifist,” “larger half,” “alone together,” and my favorite, “act naturally.” Even though these phrases do not really make sense, we human beings have no problem using them in common everyday speech.

The classic example of a linguistic paradox is the famous Epimenides paradox. This dates back more than two and a half millennia to when Epimenides (600 B.C.), a philosopher and poet who lived in Crete, complained about his neighbors in a poem called Cretica. He wrote: “The Cretans, always liars, evil beasts, idle bellies!” This seems paradoxical. If this statement is true, then since Epimenides is a Cretan, he is including himself as a liar and this line of the poem is false. In contrast, if it is false, then Epimenides is not a liar and the line is true.

There are many linguistic paradoxes similar to Epimenides’ statement. The liar paradox is a simple sentence like “I am lying,” or, “This sentence is false.”

If these sentences are true, then they are false. Furthermore, if they are false, then they are true.

The liar paradox is found in many different forms. For example, we can denote a sentence L1 and then say that L1 asserts its own falsehood:

L1: L1 is false.

Again, if L1 is true, then it is false. And if L1 is false, then it is true. Other variations of the liar paradox have sentences that are not directly self- referential. Consider the following two sentences:

L2: L3 is false.

L3: L2 is true.

If L2 is true, then L3 is false, which would mean that “L2 is true” is false and hence L2 is false. In contrast, if L2 is false, then L3 is true and L3 asserts that L2 is true. Buzz! That’s a contradiction.

It is important to note that just because sentences refer to themselves and their falsehoods does not mean there is a contradiction. Consider these two sentences:

L4: L5 is false.

L5: L4 is false.

Let’s assume that L4 is false. Then L5 is true and L4 is false. Similarly, if you start with the premise that L4 is true, you get that L5 is false, and hence L4 is true. Neither assumption leads you to a contradiction.

There are many other forms of the liar paradox:

The only underlined sentence on this page is a total lie.

The boldface sentence on this page is a blatant falsehood.

The sentence after the boldface sentence on this page is not true.

Are they true or false?

The liar paradox has been around for over 2,500 years and philosophers have devised many different ways of avoiding such contradictions. Some philosophers try to avoid these linguistic paradoxes by saying that the liar sentences are neither true nor false. After all, not every sentence is true or false. Questions such as “Your place or mine?” and commands such as “Go directly to jail!” are neither true nor false. One usually thinks of declarative sentences like “Snow is white” as either true or false, but the liar sentences show that there are some declarative sentences that are also neither true nor false.

There are those who say that the sentence “This sentence is false” is not even grammatically correct. After all, what does “This sentence” refer to? If it refers to something, we should be able to replace “This sentence” with whatever it refers to. Let’s give it a try:

“This sentence is false” is false.

This is grammatically correct and it might be true or false. But it is not self-referential and not equivalent to the original liar sentence. This is similar to the sentence

“This sentence is false” has four words. which is true, while

“This sentence is false” has five words.

is false. It would be nice to have a grammatically correct English sentence that is a self-referential paradox. W.V.O. Quine came up with a clever way around these problems. Consider the following Quine’s sentence:

“Yields falsehood when preceded by its quotation” yields falsehood when preceded by its quotation.

First notice that this is a legitimate English sentence. The subject is the phrase in quotation marks and the verb is yields. Now, let us ask ourselves if it is true. If it is true, then when you attach the subject to the rest of the sentence, as we did, we get falsehood. So the sentence is false. In contrast, what if the sentence is false? That means that when you attach the subject to the sentence, you do not get a falsehood; rather, you get a true sentence. So if you assume that Quine’s sentence is false, you derive that it is true. This is a grammatically correct English sentence that is self-contradictory.

Another potential solution to paradoxical sentences is to restrict language so as to avoid such sentences. Some have said that language should be stratified into different levels. They have declared that sentences cannot talk about other sentences of their own level or higher. For example, at the lowest level there will be sentences like “Grass is green” and “My pen is blue.” The next level will be sentences about sentences on the lowest level.

So we might have

“Grass is green” is an obvious sentence. or

“My pen is blue” has four words in it.

One goes on to higher-level phrases like

“ ‘My pen is blue’ has four words in it” is a dumb fact.

By restricting the types of sentences, we will be avoiding sentences of the form

The sentence in italics on this page is grammatically correct.

This is a sentence dealing with itself and hence is a sentence on its own level. It is declared not kosher—that is, not a legitimate part of language. Every sentence is only permitted to talk about sentences that are “below” it. If a sentence does talk about a sentence that is on its own level, that sentence is proclaimed meaningless. This stratification will ensure that there are no self-references and hence no contradictions. With such restrictions in place, linguists are fairly certain that they have banned most paradoxical linguistic sentences. However, this solution is somewhat artificial. Common human language has always dealt with some type of self- reference without problem:

- Someone says, “Oh! I am groggy today and I do not know what I am talking about.” Is he aware of saying this sentence?

- Carly Simon sings a song with the lyrics “You’re so vain, you probably think this song is about you.” But this song is about him!

- “Every rule has an exception except one rule: this one.”

- “Never say ‘never’!”

- “The only rule is that there is no rule.”

In all of these cases—and many more—human language is violating the restriction of only dealing with sentences that are “below” it. In each case, a sentence discusses itself. And yet, somehow, all these examples are a legitimate part of human language.

Another possible solution to paradoxical sentences is that human language is a product of the human mind and, as such, is subject to contradictions. Human language is not a perfect system that is free of discrepancies (in contrast to perfect systems like mathematics, science, logic, and the physical universe). Rather, we should simply accept the fact that human language is faulty and has contradictions. This seems reasonable to me.

Self-Referential Paradoxes

The cause of the problem with the liar paradox is that language can be used to describe language. In particular, one can have a sentence that discusses its own truthfulness. This ability of language to describe language is a form of self-reference. Paradoxes that arise from such self-reference are the subject of this section. While these paradoxes are not linguistic paradoxes per se, they are similar to the liar paradox and will help us understand the true nature of self-reference.

The British philosopher Bertrand Russell described a delightful little paradox that has come to be known as the barber paradox. Imagine a small isolated village in the Austrian Alps that has only one barber. Some villagers shave themselves and some go to the barber. Everyone in the village abides by the following rule: All those who do not shave themselves must go to the only barber and all those who do shave themselves do not go to the barber. This seems like a pretty innocuous rule. After all, if they can save some money by shaving themselves, why go to the barber? And if they go to the barber, why shave themselves? Now, simply ask yourself:

Who shaves the barber?

He is a villager and so if he does not shave himself, must go to the barber. But he is the barber and so he shaves himself. If he does shave himself, then, since he is the barber, he goes to the barber and does not shave himself.

We might envision the barber paradox. We split the set of villagers into two parts and look to see if the barber is on the right or left.

In contrast to the liar paradox, the barber paradox has a simple solution: The village described simply does not exist. It cannot exist because there is a contradiction inherent in its description. Our description entails a contradiction with the barber. Since the real world cannot have contradictions, the village does not really exist. There are many other villages in the Austrian Alps, but they have different setups. They might have two barbers that shave each other; they might have a female barber that does not shave; they might have long-haired hippie types who do not go to any barber regardless of need. These descriptions of other villages are totally legitimate; no contradictions result from them. But the village Russell described cannot exist.

Another clever paradox deals with adjectives in English and is called the heterological paradox or Grelling’s paradox. Consider the word English. English is an English word. In contrast, French is not a French word (it is an English word). Let us look at some other adjectives and see how they relate to themselves: Polysyllabic is polysyllabic. Monosyllabic is not monosyllabic. Pentasyllabic (made of five syllables) is pentasyllabic. Misspelled is not misspelled. Adjectival is adjectival. Female is not female. Awkwardnessfull is awkwardnessfull. Unpronounceable is not unpronounceable. In effect, we have two groups of adjectives: those that describe themselves and those that do not. All adjectives that describe themselves are called autological (from the Greek auto meaning “self” or “one’s own” and logos meaning “word,” “speech,” or “reason”) or homological. In contrast, all adjectives that do not describe themselves are called heterological (from the Greek heteros meaning “other” or “different”). So we have that English, polysyllabic, adjectival, and so on are all autological. In contrast, French, monosyllabic, unpronounceable, and so forth are all heterological. With these two categories set up, we now pose the following question:

Is heterological heterological?

Let us say that heterological is heterological. Just as

English is English ⇒ English is autological,

so too

heterological is heterological ⇒ heterological is autological

and hence heterological is not heterological. In contrast, if we take the opposite view and say that heterological is not heterological, then just as we saw that

French is not French ⇒ French is heterological,

so too

heterological is not heterological ⇒ heterological is heterological.

We have come to the conclusion that heterological is heterological if and only if it is not heterological. Buzz! This is a contradiction and troublesome.

This paradox also seems to have a simple solution: there is no word heterological, or if the word does exist, it has no meaning. We saw that if one defines heterological, then we come to a contradiction. This is similar to saying that the village in the barber paradox does not exist.

However, we cannot simply solve all problems by waving our hand and declaring that the word heterological does not exist or has no meaning. The problem is too deeply rooted in the very nature of language. Rather than dealing with the word heterological, consider the related adjective phrase “not true of itself.” Simply ask if the phrase “not true of itself” is true of itself. It is true if and only if it is not true. Are we simply to posit that “not true of itself” is not a legitimate adjectival phrase? There are no problems with any of the words in the phrase. There is nothing about the phrase that is weird like the word heterological. Nevertheless, we come to a contradiction if we use it.

The reference-book paradox is very similar to the heterological paradox. A reference book is a book that lists books in different categories. There are many reference books that list books of many different types. There are reference books that list antique books, anthropology books, books about Norwegian fauna, and so on. Certain reference books list themselves. For example, if one were to publish a reference book of all books published, that reference book would contain itself. There are also certain reference books that would not list themselves. For example, a reference book on Norwegian fauna would not list itself. Consider the reference book that lists all reference books that do not list themselves. Now ask yourself the following simple question: Does this book list itself? With a little thought, it is easy to see that this book lists itself if and only if it does not list itself. We conclude that no such reference book with such a rule for its content can exist.

Every time there is self-reference, there are possibilities for contradictions.

Bertrand Russell used the barber paradox to explain a more serious paradox called Russell’s paradox. This is more abstract than the other self-referential paradoxes we saw and is worth pondering. Consider different sets or collections of objects. Some sets just contain elements and some sets contain other sets. For example, one can look at a school as a set containing different grades, where each grade is the set of students in the grade. Some sets even contain copies of themselves. The set of all sets described in this book contains itself. The set of all sets with more than five elements contains itself. There are, of course, many sets that do not contain themselves. For instance, consider the set of all red apples. This does not contain itself since a red apple is not a set. Russell would like us to consider the set R of all sets that do not contain themselves. Now pose the following question:

Does R contain itself?

If R does contain itself, then, by definition of what belongs to R, it is not contained in R. If, on the other hand, R does not contain itself, then it satisfies the requirement of belonging to R and is contained in R. We have a contradiction.

This paradox is usually “solved” by positing that the collection R does not exist—that is, that the collection of all sets that do not contain themselves is not a legitimate set. And if you do deal with this illegitimate collection, you are going beyond the bounds of reason. Why should one not deal with this collection R? It has a perfectly good description of what its members are. It certainly looks like a legitimate collection. Nevertheless, we must restrict ourselves in order to steer clear of contradictions. The obvious (and seemingly reasonable) notion that for every clearly stated description there is a collection of those things that satisfy that description is no longer obvious (or reasonable). For the clearly stated description of “red things,” there is a nice collection of all red things. However, for the seemingly clear description of “all sets that do not contain themselves,” there is no collection with this property. We must adjust our conception of what is obvious.

Russell’s paradox should be contrasted with the other paradoxes. There are simple solutions to the barber paradox and the reference-book paradox: Those physical objects simply do not exist. And there is a simple solution to the heterological paradox: Human language is full of contradictions and meaningless words. We are, however, up against a wall with Russell’s paradox. It is hard to say that the set R simply does not exist. Why not? It is a well-defined idea. A collection is not a physical object, nor is it a human-made object. It is simply an idea. And yet this seemingly innocuous idea takes us out of the bounds of reason.

The liar paradox was summarized by one sentence:

This sentence is false.

It can also be summarized by the following description:

The sentence that denies itself.

Similarly, the other four self-referential paradoxes can be summarized by the following four descriptions:

- “The villager who shaves everyone who does not shave themselves.”

- “The word that describes all words that do not describe themselves.”

- “The reference book that lists all books that do not list themselves.”

- “The set that contains all sets that do not contain themselves.”

As you can see, all these descriptions have the exact same structure. Every time there is self-reference, there are possibilities for contradictions. Such contradictions will have to be avoided and will require a limitation. We explore such limitations throughout the book.

Before moving on, there is an interesting result that demands further thought. One might think that every language paradox has some form of self-reference. That is, there must be some chain of reasoning that is circular and returns to where it started. This was the common belief until Stephen Yablo came up with a clever paradox called Yablo’s paradox. Consider the following infinite sequence of sentences:

K1 Ki is false for all i>1

K2 Ki is false for all i>2

K3 Ki is false for all i>3

…

Km Ki is false for all i>m

Km+1 Ki is false for all i>m+1

…

Kn Ki is false for all I>n

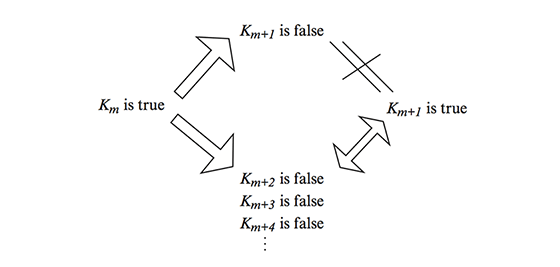

Every statement declares all the further statements to be false. Notice that no sentence ever references itself, nor is there any long chain that has some sentence referring back to itself. Nevertheless, this is a paradox in the sense that one cannot say that any sentence is either true or false. Imagine that for some m, we have that Km is true. Km says that all of Km+1, Km+2, Km+3, … are false. Splitting this up, we have that Km+1 is false and all of Km+2, Km+3, … are false. However, Km+1 says that all of Km+2, Km+3, … are false, which makes Km+1 true. Hence, by assuming that Km is true, we get a contradiction about the status of Km+1. This can be viewed in figure 2.4.

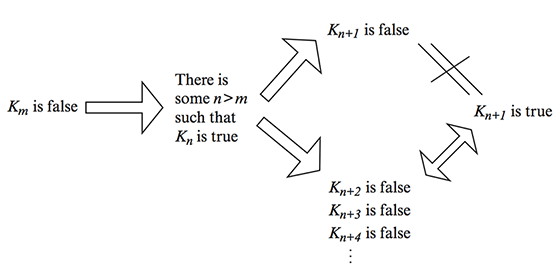

In contrast, imagine that for any m, we assume Km is false. That means that not all Kn for n>m are false and there is at least one n>m with Kn is true. But we saw that if any Kn is true, we get a contradiction as in figure 2.5.

When we assume that any Km is either true or false, we arrive at a contradiction. This is a contradiction without any self-reference.

Naming Numbers

Numbers are the most exact concepts we have. There is no haziness with the idea of 42. It is not a subjective idea where every person has their own concept of what 42 really is. And yet we will see that there are even problems with the description of numerical concepts. First a short story. In the early 20th century, the mathematician G.H. Hardy (1877–1947) went to visit his friend and collaborator, the genius Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887–1920). Hardy writes: “I remember once going to see him when he was ill at Putney. I had ridden in taxi cab number 1729 and remarked that the number seemed to me rather a dull one, and that I hoped it was not an unfavorable omen. ‘No,’ he replied, ‘it is a very interesting number; it is the smallest number expressible as the sum of two cubes in two different ways.’ ” In detail, 1729 is equal to 13 + 123 but it is also equal to 93 + 103. Since 1729 is the smallest number for which this can be done, 1729 is an “interesting” number.

This tale brings to light the interesting-number paradox. Let’s take a tour through some small whole numbers. 1 is interesting because it is the first number. 2 is the first prime number. 3 is the first odd prime. 4 is a number with the interesting property that 2 × 2 = 4 = 2 + 2. 5 is a prime number. 6 is a perfect number—that is, a number whose sum of its factors is equal to itself (i.e., 6 = 1 × 2 × 3 = 1 + 2 + 3, etc.). The first few numbers have interesting properties. Any number that does not have an interesting property should be called an “uninteresting number.” What is the smallest uninteresting number? The smallest uninteresting number is an interesting number. We are in a quandary.

There is no haziness with the idea of 42.

What went wrong here? The contradiction came about because we thought we could split all numbers into two groups: interesting numbers and uninteresting numbers. This is false. There is no way to define what an interesting number is. It is a vague term and we cannot say when a number is interesting and when it is uninteresting. “Interesting” is a feeling that a person gets sometimes and hence is a subjective property. We cannot make a paradox out of such a subjective property.

A more serious and related paradox is called the Berry paradox. The key to understanding this paradox is that in general the more words one uses in a phrase, the larger the number one can describe. The largest number that can be described with one word is 90. 91 would demand more than one word. Two words can describe ninety trillion. Ninety trillion + 1 is the first number that demands more than two words. Three words can describe ninety trillion trillion. The next number (ninety trillion trillion + 1) would demand more than three words. Similarly, the more letters in a word, the larger the number you can describe. With three letters, you can describe the number 10 but not 11.

Let us stick to number of words. Call a phrase that describes numbers and has fewer than eleven words a Berry phrase. Now consider the following phrase:

the least number not expressible in fewer than eleven words.

This phrase has ten words and expresses a number, so it should be a Berry phrase. However, look at the number it purports to describe. The number is not supposed to be expressible in fewer than eleven words. Is this number expressible in eleven words or less? This is a real contradiction.

We may also talk about other measures of how complicated an expression is. Consider

the least number not expressible in fewer than fifty syllables.

This phrase has fewer than fifty syllables. Another phrase,

the least number not expressible in fewer than sixty letters,

has fifty-nine letters. Do these descriptions describe numbers or not? And if they do describe numbers, which ones? They describe a certain number if and only if they do not describe that number. But why not? Each certainly seems like a nice descriptive phrase.

Yet another interesting paradox about describing numbers is Richard’s paradox. Certain English phrases describe real numbers between 0 and 1. For example,

- “pi minus 3” = 0.14159

- “the chance of getting a 3 when a die is thrown” = 1/6

- “pi divided by 4” = 0.785

- “the real number between 0 and 1 whose decimal expansion is 0.55555” = 0.55555

Call all such phrases Richard phrases. We are going to describe a paradoxical sentence. Rather than just stating the long sentence, let us work our way toward it. Consider the phrase

the real number between 0 and 1 that is different from any Richard phrase.

If this described a number, it would be paradoxical since the phrase would describe a number and yet it would not be a Richard phrase. However, there are many real numbers that are different from all Richard phrases. Which one is it? The problem is that this phrase does not really describe an exact number. Let us try to be more exact. The set of Richard phrases are a subset of all English phrases, and as such, they can be ordered like names in a telephone book. We can first order all Richard phrases of one word, then the phrases of two words, and so on. With such an ordered list we can talk about the nth Richard sentence. Now consider

the real number between 0 and 1 whose nth digit is different from the nth digit of the nth Richard phrase.

This is just showing how the number described is different from all the Richard phrases, but it still does not describe an exact number. The number described by the forty-second Richard number might have an 8 as the forty-second digit. From this, we know that our phrase cannot have an 8 in the forty-second position. But should our number have a 9 or 6 in that position? Let us be exact:

the real number between 0 and 1 defined by its nth digit being 9 minus the nth digit of the nth Richard phrase.

That is, if the digit is a 5, this phrase will describe a 4. If the digit is an 8, this phrase will describe a 1. And if the digit is a 9, this phrase will describe a 0. This phrase is a legitimate English phrase that precisely describes a number between 0 and 1, yet it is different from every single Richard phrase. The phrase does describe a number if and only if it does not describe a number. What to do?

These last two paradoxes can be seen as self-referential paradoxes. In a sense, they can be summarized by the following two descriptions:

- “the Berry phrase that is different from all Berry phrases”

- “the Richard phrase that is different from all Richard phrases”

From this point of view, they are simple extensions of the liar paradox. Self-reference is very common and we must be careful with it.

From The Outer Limits of Reason by Noson S. Yanofsky, published by the MIT Press.

Further Reading

Many of the paradoxes can be found in places such as Quine 1966, Hofstadter 1979, 2007, Barrow 1999, and Poundstone 1989. Sorenson 2003 is a clear and well-written introduction to paradoxes. Chapter 5 of Sainsbury 2007 covers the liar paradox and other forms of self-reference. Chapter 3 of Paulos 1980 provides a humorous look at all self-referential paradoxes. Yablo’s paradox is found in Yablo 1993.

A formal version of self-referential paradoxes can be found in Yanofsky 2003, which is derived from Lawvere 1969.