Avi Loeb doesn’t need to be a muckraker. As the head of the astronomy department at Harvard University, he sits in one of the most comfortable positions in academia. Nevertheless, he has repeatedly placed himself at the center of scientific controversies—most prominently with a series of articles and interviews suggesting that a peculiar space object known as ‘Oumuamua might have been a piece of alien technology.

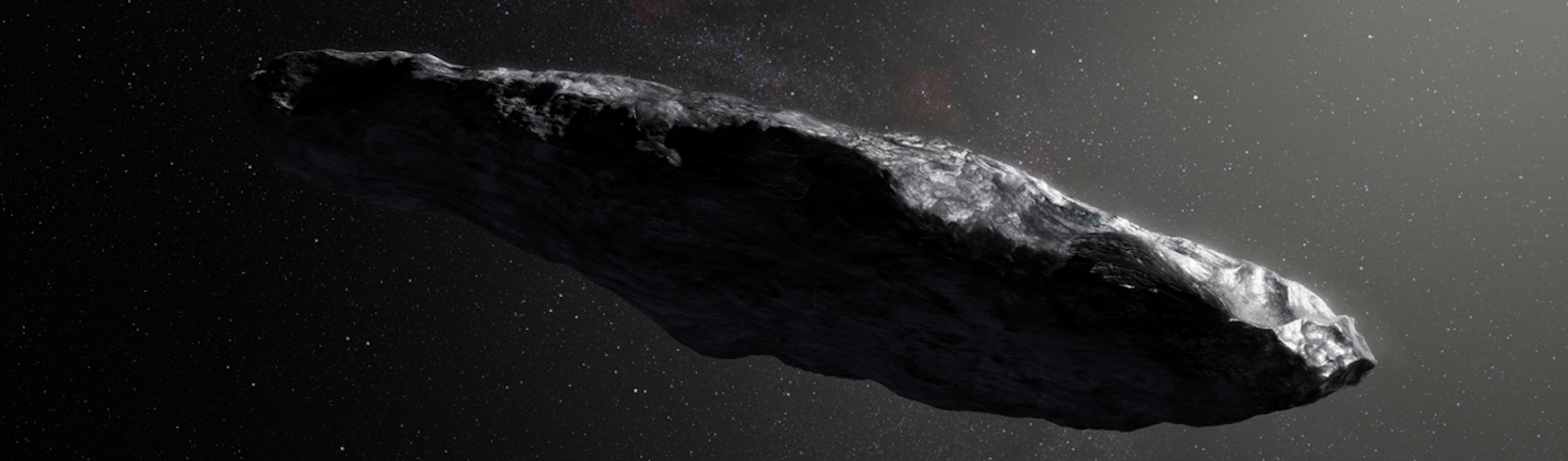

The discovery of ‘Oumuamua in the fall of 2017 instantly made headlines: It was the first object ever observed passing through our solar system from another star system. Then, the more closely astronomers observed it, the stranger it appeared. It was extremely elongated, shaped perhaps like a cigar (although it was so small that its shape had to be inferred from its changing brightness). It didn’t look quite like a comet, but not quite like an asteroid either. Strangest of all, it accelerated slightly as it passed the sun and headed back out into interstellar space.

Never one to shy away from a puzzle, Loeb wrote a paper with his postdoctoral fellow Shmuel Bialy summarizing all of ‘Oumuamua’s unusual traits and floating the possibility that perhaps the reason it looks so unusual is that it is artificial, a spacecraft designed to sail on sunlight. News writers jumped on that juicy idea. Many of Loeb’s colleagues were critical (or worse) of his willingness to entertain speculations about alien technology. But for Loeb, this was just one more opportunity to provoke the kind of wide-open conversation that he would like to see more of in his field.

Less than two years after ‘Oumuamua, astronomers have discovered a second interstellar visitor, Comet Borisov, currently making its closest pass by the sun. There is nothing strange about this one; it looks exactly like a conventional comet. Loeb is not at all put off by that. “When you walk down the street and notice a weird person, the fact that later on you encounter many normal people does not take away the weirdness of that unusual person. In fact, it enhances it,” he says. I caught up with Loeb to hear more about his thoughts on alien life, academic culture, and the scourge of preconceptions.

You created a stir last year with your comments that the interstellar comet ‘Oumuamua could be an alien artifact. What prompted you to stake out such a controversial position?

There are several popular themes in current scientific research that are shaped by the sociology of science but do not necessarily have a good reasoning behind them. I’ll give you an example. There is a lot of work in mainstream particle physics on extra dimensions. This is something unproven and completely speculative. It started with Einstein trying to unify his theory of gravity with quantum mechanics. Now it’s considered completely legitimate to invoke extra dimensions. String theory, the leading unified theory, has nothing to show in terms of verification, but it’s considered mainstream. You have a whole community of people working on it for 40 years, and nobody is raising their brows about it.

You never know the truth before you actually prove it.

At the same time, the search for extraterrestrial civilization is, to my mind, not speculative at all. It’s much less imaginative than extra dimensions. It’s based on two facts: one, that we exist, and two, that there is large number of stars with planets similar to the Earth. About a quarter of all the stars have planets the size of the Earth in the habitable zone, where they could have liquid water on the surface and the chemistry of life as we know it. If you roll the dice so many times, it’s possible that some of these planets will have biology and advanced civilization.

There is nothing speculative or imaginative about this. It’s just saying that if you do the same experiment again you could get the same results, as compared to imagining dimensions that we don’t know exist.

But so far we have evidence of life on only one planet, our own. Isn’t it equally speculative to imagine that alien civilizations exist?

Look at another example, dark matter. We see moving in galaxies in orbits that imply much more mass than we can associate with these stars, with ordinary matter, so we say that there is an additional form of matter, dark matter. We haven’t detected it. It sounds plausible, but it’s still unproven. It’s just based on an anomaly, the fact that the ordinary matter behaves in an unexpected way.

When I saw an anomaly in the case of ‘Oumuamua, all I was doing was following the standard scientific process of saying, “What can explain it?” I don’t see how that’s any different than trying to invoke dark matter to explain the motion of ordinary matter in galaxies or in cosmology. It’s a hypothesis that you put on the table, as plausible as any other hypothesis. The strange thing is that people are afraid to bring up the possibilities of an artificial origin. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy: If you, ahead of time, you set the prior that there’s zero probability for it to be artificial, then obviously you will never find it to be artificial. You will be happy but you might be wrong.

How do you propose that scientists steer away from those kinds of preconceptions?

The point of doing science is not to have a prejudice. Prejudice is based on your experience from the past. If you want to allow yourself to make discoveries, that means that the future will not be the same as the past. You have to give up on prejudice. You have to give up on gut feelings. Gut feeling is based on past experience. If you encounter something really, your gut feeling will give you the wrong guidance.

What are some good historical examples of how gut feelings have led people astray?

A very good one is what happened to Einstein when quantum mechanics was discovered. He resisted the notion that the reality is based on probabilities. He believed that there must be determinism, just like in classical physics, and that you can infer the future from the past in a deterministic way.

Why would we not expect another civilization to have sent things into interstellar space?

So he thought that the interpretation of quantum mechanics that Niels Bohr came up with was wrong and suggested experiments that would test it. Einstein called the notion of action at a distance in quantum mechanics “spooky.” But experiments after his death confirmed the notion of quantum mechanics that is in contradiction to Einstein’s gut feeling. That shows you that gut feelings based on the past can be wrong. It misguided Einstein and led him to work for years on trying to argue otherwise. Nobody would say that Einstein’s gut feeling was a bad approach, because it also led him to the special theory of relativity, but it’s not always the right approach.

That all sounds reasonable in principle, but how can we get away from gut feelings in practice—not just in astronomy, but all of science?

What I’m saying is, the correct way of doing science is to be open to possibilities and rule them out based on evidence. Evidence is the key. Data is the key. Reality sometimes is more imaginative than we are. Just think about the possibility that there are other civilizations. There’s nothing speculative about it. There is a chance that some objects would enter the solar system from another civilization.

We are starting now to send objects outside our solar system. Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 left the heliopause, the place where the solar wind meets the interstellar medium. So why would we not expect another civilization to have sent things into interstellar space? We might one day get a message in a bottle. It opens a new frontier. We should examine each and every interstellar object entering the solar system to check if it’s natural or not. Even if most of the time it will be natural, every now and then we might be surprised. What do we gain by putting blinders on our eyes?

It sounds like you are describing a problem of prejudice that far predates modern science.

Yes, it’s sort of similar to in the days of Galileo. Before that, people thought that heavy objects must fall faster than light objects. Galileo said, “Let’s not have a prejudice. Let’s check it experimentally.” In his experiments, he showed that heavy objects fall as fast as light ones. That was against the gut feeling of most people. Today, many things that seem very natural to us, very acceptable to discuss on Twitter, are wrong. The nature of ‘Oumuamua and other interstellar objects won’t be determined by what people say on Twitter. We can convince each other we are right and give each other awards, but the object will be whatever it is.

Still, you received a lot of criticism and a bit or ridicule for suggesting that ‘Oumuamua could be an alien spaceship. Doesn’t that concern you?

I don’t care about how I am viewed, especially how people view me on Twitter or elsewhere. All I care about is trying to understand nature. That’s what guides me, and the fact that there was a lot of publicity to this story does not count much in my book. I know that the same newspaper that was read today by a lot of people is used tomorrow to wrap fish. What I really care about is whether we detected the first evidence of another civilization. That’s what really attracts my attention.

That’s easy for you to say as the tenured head of the astronomy department!

Of course, if I was in a much more vulnerable position—let’s say a postdoc or a student—I would have to be worried about what other people think. But the whole idea of getting tenure in academia is to allow you to be free in your mind, to examine things the way they are and not to be afraid of public opinion, and to say what you think is the correct thing. Unfortunately, many people don’t take advantage of this privilege. Once they get tenure, many of my colleagues become even more conservative because they want to protect their image. They want to get the prizes, they don’t want make mistakes. But learning experience is full of missteps and making mistakes.

I mean, even Einstein made mistakes. I mentioned one of them earlier, his resistance to quantum mechanics. He also claimed that there are no black holes, and that there are no gravitational waves. If you dare to innovate, if you try to do new things, to make discoveries, even if you try as hard as you can, you make mistakes because you can never do everything right. It’s impossible and it’s not human. You never know the truth before you actually prove it. Mistakes are part of the process, and you have to allow for that. People in the business world know that. In venture capitalism, many of the ventures failed.

Are you suggesting that academia could take some lessons in open thinking from the private sector?

Surprisingly, people in academia are much more conservative than in the business world, even though in the business world they have to make a profit. You would think that people would be more conservative, because they have to make a profit, but they realize that in order to make a profit, you need to take some risks. And in the process of taking risks, sometimes you fail. Sometimes you make mistakes, and you can’t maintain an image of always being right.

Unfortunately, in academia people get so attached to their egos, that they give up on taking risks, that they scrutinize anyone else that is taking risks. That’s not healthy for the process of science.

One concern I’ve heard is that academics are already under fire from science skeptics. Don’t you worry that far-out speculation feeds into today’s anti-authority mood?

Sure, some people say, “Oh, we should be very careful, because if the public sees that we have some uncertainty, that we are not sure about something, then they would say, ‘Okay, well then maybe global warming is not real, because…’” But I argue the opposite.

I know that the same newspaper that was read today by a lot of people is used tomorrow to wrap fish.

The reason that people claim academia is the part of the elite is because of this tendency of researchers to go into to a closed room to discuss things among themselves. They come out with the statement only when it’s clear to them. It’s better to let the public see the process the way it is. The scientific process most of the time is uncertain, because you’re not sure—you collect evidence until you’re sure. They should see that most of the time the scientists are collecting evidence in order to become confident in their statements, and during this process they are not confident, because they don’t yet know for sure. Then there would be much more credence to the process.

The layman would realize, “This is just like how I would approach a problem. It’s a human activity. When they tell me that there is climate change and all of them say the same thing, it seems like it’s based on lots of evidence. It wasn’t dumped on me without me seeing the process of arriving at it.” I think transparency is extremely important, and it’s exactly opposite of the view expressed by the scientists who say, “Oh no, let’s keep it to ourselves.”

Who are good role models for being a free-thinking scientist?

There aren’t so many, and that’s unfortunate! Freeman Dyson is an excellent example; I’m following his path in many ways. Richard Feynman addressed issues without paying too much attention to what other people thought. Fritz Zwicky is another, less well-known person from history. It’s quite amazing if you think about what he did, he discovered dark matter and he discovered supernovae. He was not liked socially, his way of dealing with people was not particularly courteous, but it’s not by chance that he discovered so many things. He didn’t pay too much attention to what other people were doing at the time. He did his own thing.

If you go back in time, it’s easier to find examples because back then most of the community was thinking incorrectly about science. In a way, Einstein was an example early on in his career and Galileo—there are many historical examples. So, yeah, I think it’s a little more difficult to go down this path because you have to be confident that you don’t make too many wrong moves because otherwise you lose credibility. But at the same time, if you pay attention to evidence, then you remain consistent.

Even beyond the professional concerns, it’s just hard to live your life that way sometimes.

One thing I told my wife when I married her was that she doesn’t have to worry about me having an affair, because it’s just too complicated for me to maintain two truths. And I remember what I told her: If I stick to the truth, it’s easy because I don’t need to remember what I said to her. And she said, “That’s not so romantic!” And I said, “Well, but you can count on it.”

The way I do science is quite similar. I tried to maintain my childhood curiosity, my childhood innocence and not to be contaminated by belonging to clubs. I don’t like belonging to clubs of people that say the same thing or societies that force you not to deviate from whatever everyone else is saying or big groups. Usually I work with one person or two people on every paper. And I’ve written over 700 papers. I try to keep my authenticity and not lose it. That’s not easy because I’m the chair of the astronomy department at Harvard and director of two centers.

If you have an alien civilization, its biological existence on the surface of a planet is just the beginning.

From that elevated perspective, what do you see as the reasons that academics who have the authority to be adventurous nevertheless choose not to do so?

People in those positions very often are, first, afraid about their image and, second, because they have a lot of other people around them, they average their views to represent what other people are saying. I don’t do that. And nevertheless, if you ask the people around me, I think they would tell you that I encourage their sense of independence. I give each student a completely different project to work on. I try to enhance diversity as much as possible—people from different ethnic backgrounds, gender and so forth.

What matters the most is the substance, not so much superficial appearance and not so much the labor. I don’t care about my labors, the fact that I’m chair of the department. Anyone that comes to speak with me, I would treat that person with as much respect whether they are a high school student, a distinguished professor, or a plumber that comes to fix the sewer in my home. I often speak for an hour with such people as well, and I enjoy it very much—much more so, often, than speaking with my colleagues, because they do not pretend that they know more than they actually know.

As my friend Bill Nye often says, “Everybody knows something that you don’t know.”

Exactly. And you learn from speaking to other people, you learn from nature. We should just open our minds and not be too attached to our ego. That’s the main message. And we should use the same modesty in terms of us being special. People that believe that there are no civilizations, no life, elsewhere. These people show arrogance because they think that we are special.

With that in mind, where do we go next in studying interstellar objects and looking for signs of anything unusual? ‘Oumuamua is long gone, and Comet Borisov looks like a completely normal, natural comet.

There was a paper that I wrote with an undergraduate student at Harvard, Amir Siraj. We considered a small subset of interstellar objects would pass very close to Jupiter and get trapped in the solar system. We found that you can distinguish them from asteroids that were born in the solar system based on their orbits. The ones that are getting trapped could be on very inclined orbits. We have identified four objects that are on inclined orbits consistent with what we predicted. They should be looked at, because they might have interstellar origin. The way to find out is by getting close to these objects, trying to determine their composition and trying to see if they look different.

With Amir Siraj we also identified a likely interstellar meteor that reached Earth in 2014. This enables a new method for studying the composition of small interstellar objects as they burn up in Earth’s atmosphere.Another approach is to wait for LSST [the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, due to begin operating this coming year] to find more of interstellar objects. Then we’ll use all available instruments to probe it as much as possible, as we are doing now with Comet Borisov.

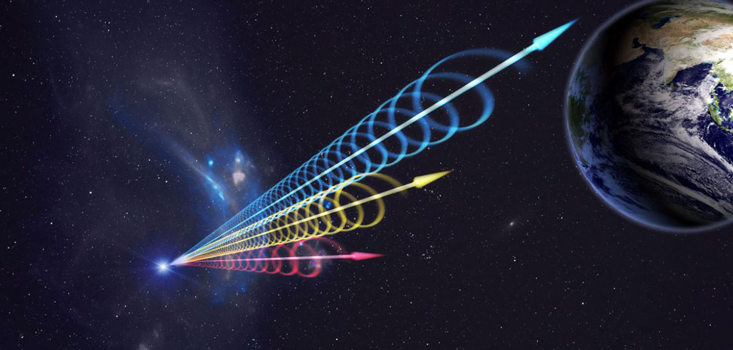

What about more exotic ways to search for alien technology? Peter Klupar at Breakthrough Starshot suggested looking for laser beams used to launch spaceships from other planets.

Yes, I wrote the paper!

Of course you did.

I had several postdocs thinking about what propulsion technology would be best to reach high speed. We were thinking about lightsails [spacecraft propelled by intense laser beams or other radiation] and said, “Suppose lightsail technology is used for moving cargoes between an Earth-like and a Mars-like planet in another planetary system. Would we be able to see the beam used to push the sails?” We did a calculation and we showed that it could be seen if, especially if the beam is radio waves—and radio propulsion is particularly appropriate for moving massive cargoes. It would appear like a radio flash or a radio burst.

In another paper, in 2017, we argued that perhaps some fast radio bursts [mysterious pulses of radio waves that have been observed in various parts of the sky] are associated with this. At the time, there was one known fast radio burst that repeated, and it appeared to be at cosmological distances, in another galaxy. At that kind of distance, you’d need extreme power for the launch system to be visible to us. But if some of the bursts originate in our own galaxy, you don’t need such a powerful thing. Then it’s completely plausible that with modest means [an extraterrestrial civilization] could be associated with that signal.

So you think it’s worth at least checking to see if radio flashes could be the result of alien civilizations. What other unconventional ways might we search for them?

One is the redistribution of heat and light on the surfaces of planets. If you have a civilization there, it might try to redistribute the light and heat so that the dark side is not so dark and cold. We might look for industrial pollution or artificial light. Then there’s the possibility of the surface of the planet has a reflectance that is associated with materials that are not natural, like photovoltaic cells. There are many possibilities.

Our imagination is limited by what we are doing, so as our technology develops, I have more ideas about these. About 60 years ago when we started using radar and radio signals for communication, SETI started searching for radio signals. Now we know of lasers, we know about lightsails and so forth, so there are many more things that we can search for. It would be very natural, as our technology improves, to look for things that we are developing that we never envisioned before.

What about a civilization that is millions of years ahead of us, or that vanished many millions of years ago?

If you have an alien civilization, its biological existence on the surface of a planet is just the beginning. It’s quite likely that it then starts spreading and leaving many more marks away from the planet. I would think that debris in space would be much more common than artifacts on the surface. It would mostly be technological equipment, but such things would probably be small and not reflect much starlight, so it would be hard to see them with existing telescopes. I would not be surprised if there is a lot of traffic out there, and that once we send our own probe outside the solar system we will get the message back saying, “Welcome to the interstellar club.”

It’s much more likely that, rather than visiting a planet and seeing something on its surface, we will start seeing flying objects that we just didn’t notice before. I think there are potentially many things flying out in space that are signatures of other civilizations but that are too small to detect with existing telescopes. The key would be to find ways of detecting those things.

Could this explain the “Fermi paradox,” the puzzle that intelligent life should have filled the universe but we see no sign of it?

My answer to Fermi’s paradox is dual. One is that many technology civilizations die soon after they mature technologically because they develop the means for their own destruction, so they are short-lived. But more importantly is that there is no reason for a technological civilization to announce its existence by sending out powerful signals on purpose. Most of the time they would send the equipment, and that’s not easy to detect. Once we reached the threshold of being able to detect such things—and maybe ‘Oumuamua was the first—we will see a lot of them.

It could be what happened with the search for gravitational waves. When I was a post-doc, people were laughing at the attempts to build a gravitational-wave detector. My mentors at Princeton were very opposed to this search because they thought that it would take away funding from the astronomy community, and it had no chance of success—that the signals were too weak and difficult to detect. Even the theorists were expecting a very low signal to noise ratio. Then when the first event came in 2015 it was obvious.

Once you pass a certain threshold, suddenly you see all these things. I think the same will apply to detecting evidence for other civilizations.

Corey S. Powell is an Earth-based science writer and editor, and co-host of the Science Rules! podcast. He is a frequent presence on Twitter: @coreyspowell

Lead image: Illustration of ‘Oumuamua by ESO/M. Kornmesser