Latest

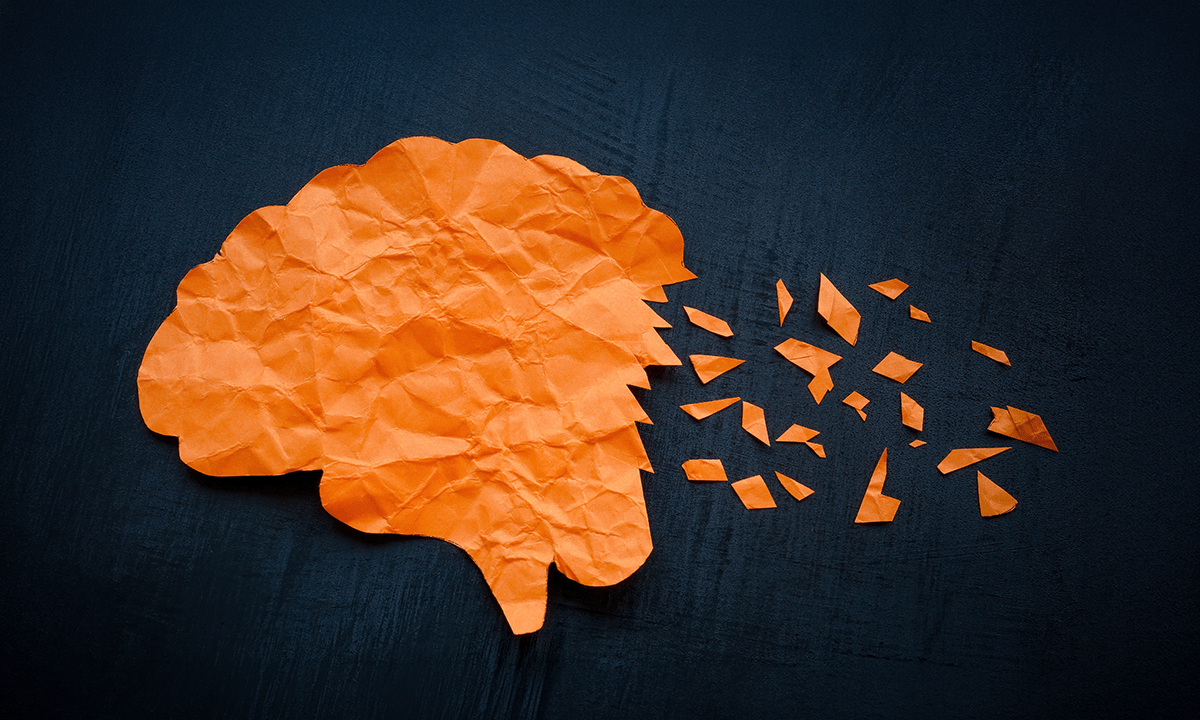

Some Memories Live in the Brain Even If We Can’t Recall Them

It’s all coming back to me now

Latest Stories

Restoring Panama to When Prehistoric Beasts Roamed the Jungle

The Central American nation never fully recovered from the loss of its megafauna

Physicists Uncover How Long It Takes to Get the Last Drop of Syrup

How to tackle a common kitchen problem with fluid dynamics

Psychology

See more PsychologyLaughing Off Your Mistakes Makes You Seem More Competent

“People often overestimate how harshly others judge their minor social mistakes”

Why You’re More Likely to Develop AI-Psychosis than to Join a Cult

Philosopher Lucy Osler on the insidious appeal of AI Chatbots

Blame Your Parents for Your Extreme Aversion to Snakes

But recognize that it’s a useful survival trait

Environment

See more EnvironmentThe Ancient Cold Snaps That May Have Shaped Human Evolution

Here’s when Earth’s climate became chaotic

Is a Strictly Enforced Fishing Ban Saving the Yangtze?

Ecologists detect promising, early signs of river recovery

The Long, Dirty History of Our Capitol’s Waters

The recent Potomac River disaster follows centuries of pollution—but things are looking up

Get unlimited, ad-free Nautilus. Become a member today.

History

See more HistoryHow Three Students Designed an Atomic Bomb

A top-secret 1960s project tasked physics postdocs with building The Bomb

The Thrill of Science in 2042

A science historian explains how science got its groove back. A fictional dispatch from the future.

How Energy Politics Played Out on the White House Roof

The quick removal of Jimmy Carter’s futuristic solar panels echoes more recent feuds over renewables

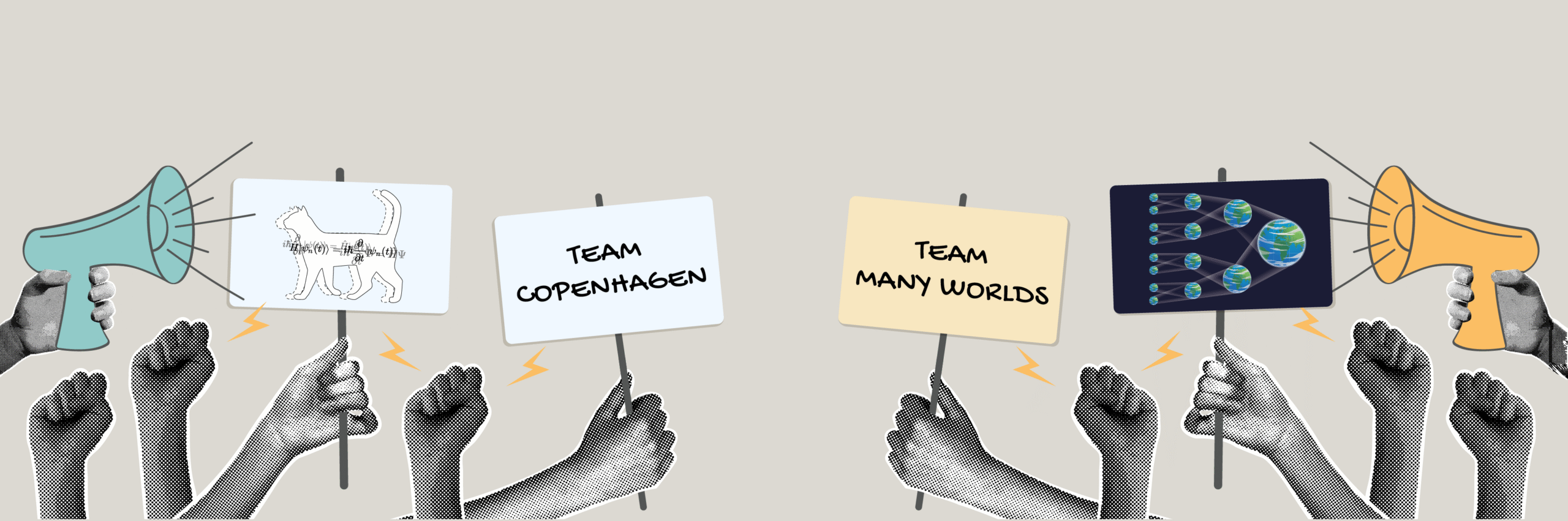

Physics

See more PhysicsNo More Tears? Scientists Take a Keen Eye to Onion Slicing

New research sheds light on a familiar problem, with important implications for food safety

Communication

See more CommunicationWhat Would Richard Feynman Make of AI Today?

The scientific sage was always suspicious of grand promises delivered before details were understood

Get the Nautilus newsletter

Cutting-edge science, unraveled by the brightest living thinkers.

Sociology

See more SociologyThe Vibes Have Been Off in the US for Decades

New survey analysis reveals a sense of national deterioration

Does Belief in God, not Political Party, Drive Conservatism?

Religious “nones” may be less socially liberal than they used to be

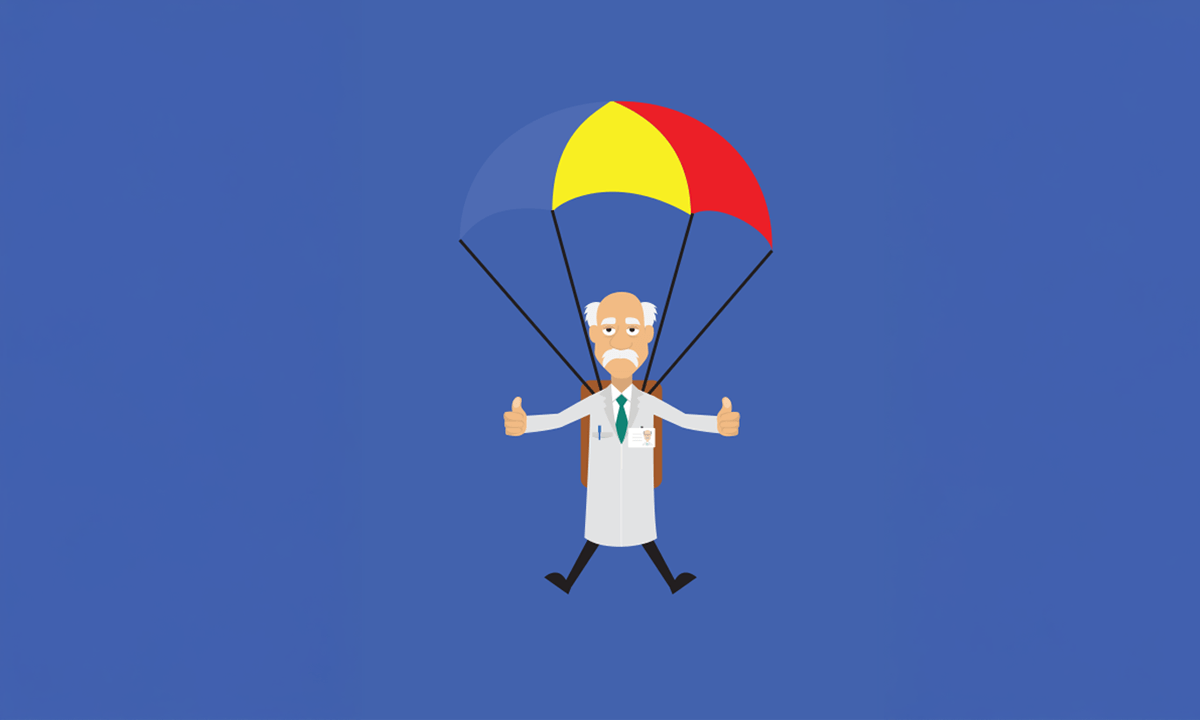

Parachute Science Continues to Prevail in Global South Biodiversity Studies

The privilege of describing new species is skewed to Global Northerners

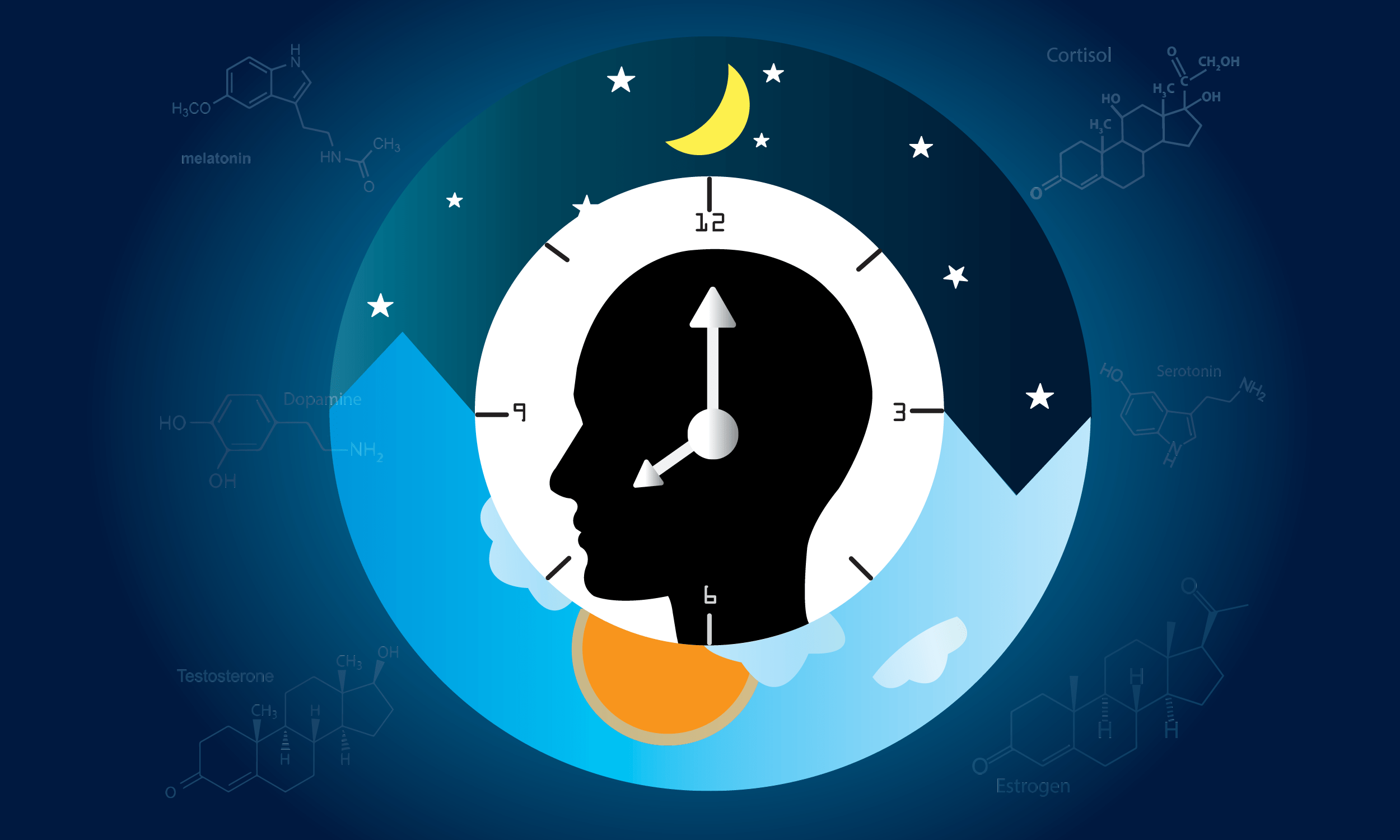

Your Biological Clock is More Complex Than You Think

Prepare for Daylight Saving Time by taking a tour of your internal timekeeping machinery

More recent posts

See all postsThe Dainty Dinosaur That’s Rewriting Evolutionary History

New alvarezsaur fossil offers a Cretaceous missing link

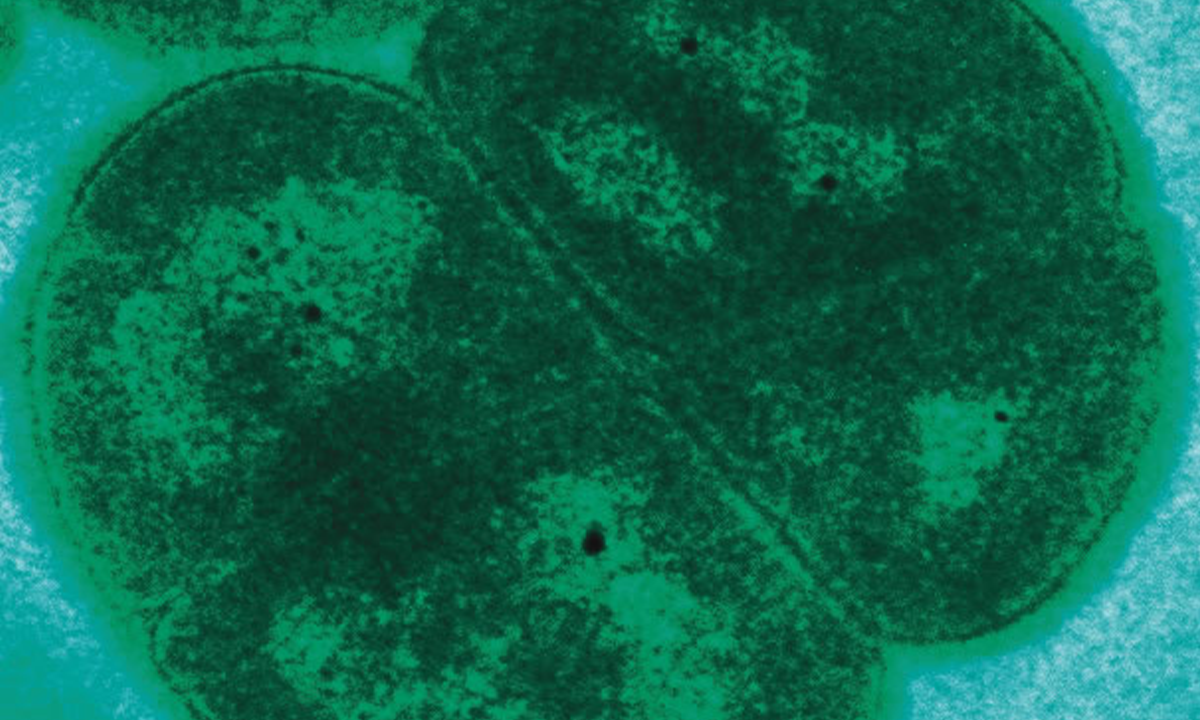

These Bacteria Beat Cancer By Eating Cancer

They’re being engineered to devour tumors from the inside out

Koalas Recover Genetic Diversity as Populations Expand

Their rebound shows resilience after a severe genetic bottleneck

Watch How Planet-Hopping Microbes Can Survive Asteroid Strikes

This polyextremophile bacterium could survive an interplanetary trip

When Scientists Are Dinosaurs

At the paleontology conference, her new theory was shouted down

Paleontologists Solve the Mystery of a Twisted Jawbone With Sideways Teeth

The Tanyka was a little like a platypus

World’s Largest Acid Geyser Erupts, Right in Our Backyard

Yellowstone National Park is home to the world’s most impressive geysers

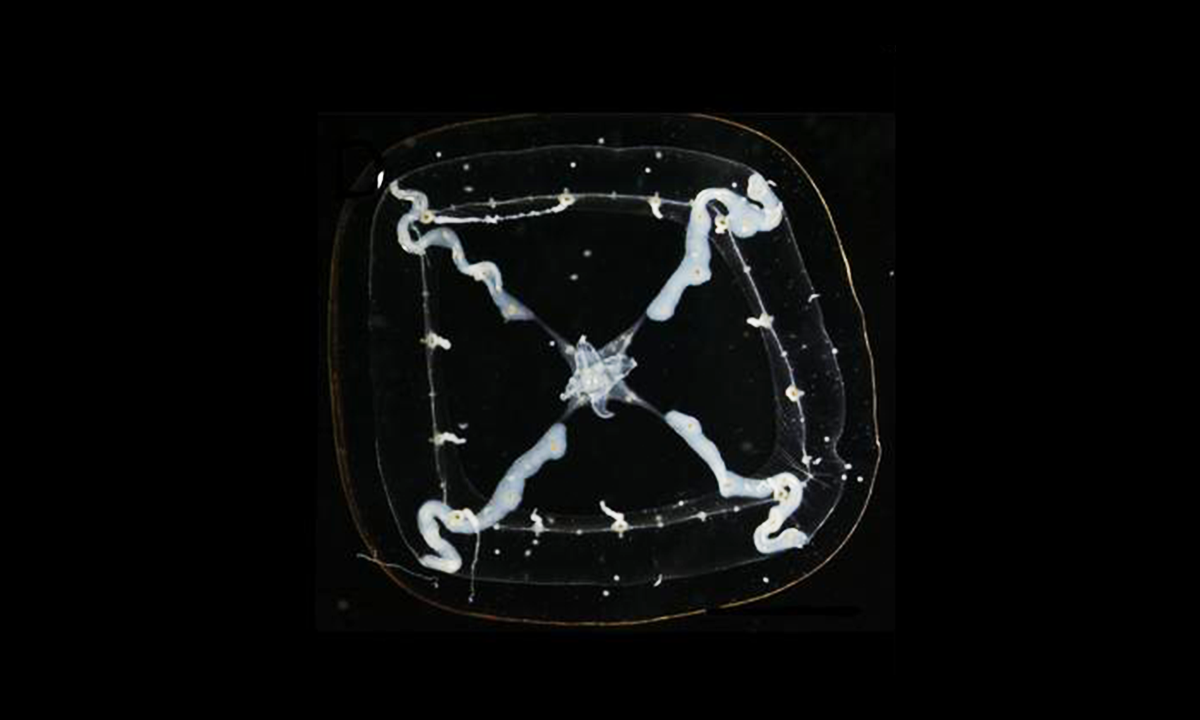

Watch How Water Bears Can Survive in Martian Dirt

There’s a way for the tiny resilient creatures to thrive even on the red planet