For an empirical science, physics can be remarkably dismissive of some of our most basic observations. We see objects existing in definite locations, but the wave nature of matter washes that away. We perceive time to flow, but how could it, really? We feel ourselves to be free agents, and that’s just quaint. Physicists like nothing better than to expose our view of the universe as parochial. Which is great. But when asked why our impressions are so off, they mumble some excuse and slip out the side door of the party.

Physicists, in other words, face the same hard problem of consciousness as neuroscientists do: the problem of bridging objective description and subjective experience. To relate fundamental theory to what we actually observe in the world, they must explain what it means “to observe”—to become conscious of. And they tend to be slapdash about it. They divide the world into “system” and “observer,” study the former intensely, and take the latter for granted—or, worse, for a fool.

A purely atomic explanation of behavior may be just that: an explanation of what atoms do. It would say nothing about brains, much less minds.

In their ambitions to create a full naturalistic explanation of the world, physicists have some clues, such as the paradoxes of black holes and the arbitrariness of the Standard Model of particles. These are our era’s version of the paradoxes of atoms and light that drove Einstein and others to develop quantum mechanics and relativity theory. The mysteries of the mind seldom come up. And they should. Understanding the mind is difficult and may be downright impossible in our current scientific framework. As philosopher David Chalmers told a Foundational Questions Institute conference last summer, “We won’t have a theory of everything without a theory of consciousness.” Having cracked open protons and scoured the skies for things that current theories can’t explain, physicists are humbled to learn the biggest exception of all may lie in our skulls.

Solving these deep problems will be a multigenerational project, but we are seeing the early stages of a convergence. It has become a thing for theoretical physicists to weigh in on consciousness and, returning the favor, for neuroscientists to weigh in on physics. Neuroscientists have been developing theories that are comprehensive in scope, built on basic principles, open to experimental testing, and mathematically meaty—in a word, physics-y.

Foremost among those theories is Integrated Information Theory, developed by neuroscientist Giulio Tononi at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. It models a conscious system, be it brain, bot, or Borg, as a network of neurons or equivalent components. The theory says the system is conscious to the extent that its parts act together in harmony. The underlying premise is that conscious experience is psychologically unified—we feel our selves to be indivisible, and our sensations form a seamless whole—so the brain function that generates it should be unified, too.

These components are on-off devices wired together and governed by a master clock. When the clock ticks, each device switches on or off depending on the status of the devices to which it is connected. The system could be as simple as two components and a rule for how each affects the other—a light switch and a light bulb, say. At any moment, that system could be in one of four states, and moment by moment, it will flit from one state to another. These transitions could be probabilistic: A state might give rise to one of several new states, each with some probability.

To quantify the cohesion of a system and its claim to being conscious, the theory lays out a procedure to calculate the amount of collective information in the system—information that is smeared out over the whole network rather than localized in any individual piece. Skeptics raise sundry objections, not least that consciousness could never be reduced to a single number, let alone the measure that Tononi proposes. But you don’t need to buy the theory as a full description of consciousness in order to find it a useful tool.

For starters, the theory could help with the puzzles of emergence that arise in physics. One of the most striking features of the world is its hierarchical structure, the way that ginormous numbers of molecules obey simple rules such as the ideal-gas law or the equations of fluid flow, or that a crazed hornet’s nest of quarks and gluons looks from the outside like a placid proton. Entire branches of physics, such as statistical mechanics and renormalization theory, are devoted to relating processes on different scales. But as useful as higher-level descriptions can be, physicists conventionally assume they are mere approximations. All the real action of the world occurs at the bottom level.

For many, though, that is perplexing. If only the microscopic scale is real, why does the world admit of a higher-level description? Why isn’t it just some undifferentiated goop of particles, as indeed it once was? And why do higher-level descriptions tend to be independent of lower-level details—doesn’t that suggest the higher levels aren’t just parasitic? The success of those descriptions would be a miracle if there were no real action at higher levels. And so the debate rages between those who think higher levels are just a repackaging of subatomic physics that we humans happen to find convenient, and those who think they represent something genuinely new.

Tononi and his colleagues had to wrestle with the very same issues in creating Integrated Information Theory. “Scale is an immediate rejoinder to IIT,” says Erik Hoel, Tononi’s former student and now a postdoc at Columbia University. “You’re saying the information is between interacting elements, but I’m composed of atoms, so shouldn’t the information be over those? … You can’t just arbitrarily say, ‘I choose neurons.’ ”

Any network is a hierarchy of subnetworks, sub-subnetworks, all the way down to the individual components. Which of these nested networks is conscious? Our nervous system stretches from head to toe, and its neurons and other components are complex little creatures in their own right. Yet our conscious experiences arise in specific areas of the cerebral cortex. Those are the places that light up in a brain scan when you’re performing tasks that you’re aware you’re performing. You could lose much of the rest of the brain, and although you might not be happy about it, at least you’d know you weren’t happy about it. Three years ago, a 24-year-old woman checked into a Chinese hospital complaining of dizziness and nausea. The doctors did a CAT scan and found a big hole in her brain where the cerebellum should have been. Though deprived of three-quarters of her neurons, she showed every sign of being as conscious as any of us are.

Physicists face the same hard problem as neuroscientists do: the problem of bridging objective description and subjective experience.

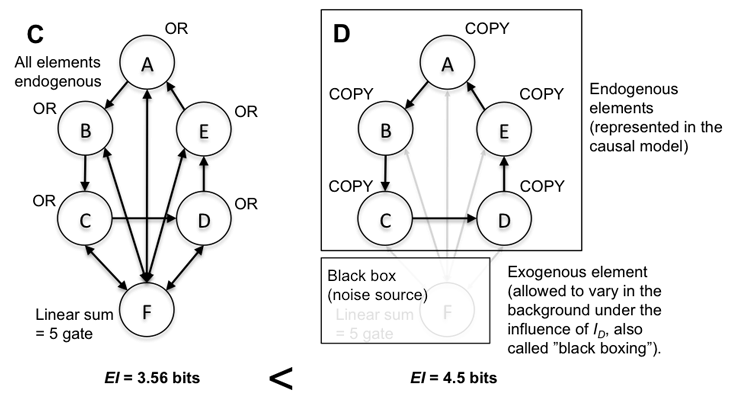

What’s so special about the cortex? Why isn’t your arm conscious, like an octopus’? Why aren’t we vast societies of willful neurons, or of enzymes within neurons, or of atoms and subatomic particles? To explain why consciousness resides where it does, Tononi, Hoel, and colleagues Larissa Albantakis and William Marshall had to come up with a way to analyze hierarchical systems: to look at activity on all scales, from the whole organism down to its smallest building blocks, and predict where the mind should reside. They ascribe consciousness to the scale where the collective information is maximized, on the assumption that the dynamics of this scale will preempt the others.

Though inspired by the nervous system, Integrated Information Theory is not limited to it. The network could be any of the multilayered systems that physicists study. You can leave aside the question of where consciousness resides and study how the hierarchy works more generally. Hoel has set out to develop a standalone theory of hierarchical causation, which he discussed recently in an entry for this year’s Foundational Questions Institute essay contest and a paper last week in the journal Entropy.

An approach based on Integrated Information Theory allows for the possibility that causation occurs on more than one level. Using a quantitative measure of causation, researchers can calculate how much each level contributes to the functioning of a system, rather than presume an answer at the outset. “If you don’t have a good measure or concept of causation,” Hoel says, “then how are you sure about your claims that the microscale is necessarily doing all the causal work?”

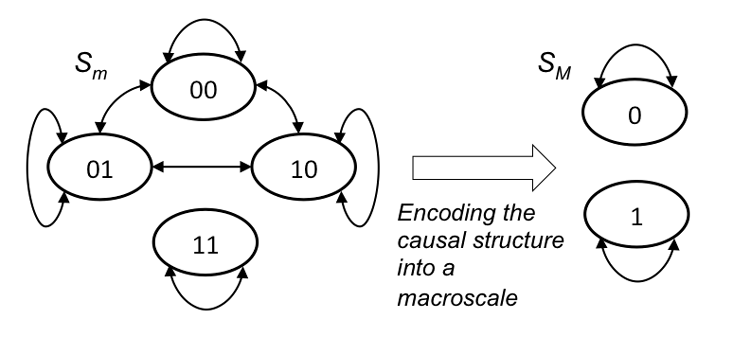

As a physicist, your goal is to create the maximally informative description of whatever you are studying, and the original specification of the system isn’t always optimal. If it contains latent structure, you’ll do better by lumping the building blocks together and tweaking their linkages to create a higher-level description. For example, if the components in the two-component system always change in lockstep, you might as well treat them as a single unit. You gain nothing by tracking them independently and, worse, will fail to capture something important about the system.

Hoel focuses on three ways that the higher level can improve on the lower level. First, it can hide randomness. Air molecules endlessly reshuffle to no lasting effect; their myriad arrangements are all basically the same—a difference that doesn’t make a difference. Second, the higher level can eliminate spoilers. Sometimes the only role of a component is to gum up the other linkages in the system, and it might as well be removed. Its effect can be captured more simply by introducing some randomness into the behavior of the remaining components. Third, the higher level can prune out redundancy. Over time, the system might settle into only one of a few states; the others are irrelevant, and higher levels gain in explanatory value by dropping them. This kind of attractor dynamics is common in physical systems. “The higher scale is not just a compressed description,” Hoel says. “Rather, it’s that by getting rid of noise, either in the case of increasing determinism or by reducing redundancy, you get a more informative description.” Given the new description, you can repeat the process, looking for additional structure and moving to an even higher scale.

How to look for structure—well, that’s something of an art. The connection between levels can be extremely non-obvious. Physicists commonly construct a higher level by taking an average, but Integrated Information Theory encourages them to approach it more like a biologist or software engineer: by chunking components into groups that perform some specific function, like an organ of the body or a computer subroutine. Such functional relations can be lost if all you do is take the average. “Molecules inside the neurons have their particular functions and just averaging over them will not generally increase cause-effect power, but rather make a mess,” Albantakis says.

If the base level is deterministic and free of redundancy, it already provides an optimal description by the standards that Hoel sets out, and there is no emergence. Then physicists’ usual intuition—that any higher level is good only as an approximation—holds. Arguably, the very concept of causation breaks down for such a system, because the system is fully reversible; there is no way to say that this causes that, because that could well cause this. Conversely, the base level could be totally uninformative while higher levels show strong regularities. This recalls speculations in fundamental physics, which go back to mathematician Henri Poincaré and physicist John Wheeler, that the root level of nature is completely lawless and all the laws of nature emerge only in the aggregate.

The higher level does lose something; by definition, it doesn’t capture the system in every detail. But the tradeoff is usually worth it. The proof, Hoel says, lies in theorems from communication theory. You can think of the current state of the system as a transmitter, the subsequent state as a receiver, and the relationship between the two as a wire. “Each state is a message that causal structure is sending into the future,” he says. Randomness and redundancy are like noise on the line: They corrupt the message.

When a communications line is noisy, you can often shove data down it faster by using an error-correcting code. For instance, you might transmit in triplicate, dispersing the copies to make them likelier to get through. On the face of it, that cuts the data rate to a third, but if it lets you fix errors, you can come out ahead. In a precise mathematical sense, a higher-level description is equivalent to such a code. It squelches noise that drowns out the essential dynamics of the system. Even if you lose detail, you have a net gain in explanatory traction. “Higher scales offer error correction by acting in a similar manner to codes, which means there is room for the higher scales to do extra work and be more informative,” Hoel says.

For instance, in the two-component, four-state system, suppose that one of the states always gives rise to itself, while the other three cycle among one another at random. Knowing what state the system is in gives you, on average, 0.8 bit of information of what comes next. But suppose you lump those three states together and use them to store one state in triplicate. The system is now smaller, just two states, but fully deterministic. Knowing its present state gives you 1 bit of information about the successor. The extra 0.2 bit reflects structure that the original description concealed. You could say that 80 percent of the causal oomph of the system lies at its base level and 20 percent at the higher level.

Joseph Halpern, a computer scientist at Cornell who studies causation, thinks Hoel is on to something. “The work has some interesting observations on how looking at things at the macro level can give more information than looking at them at the micro level,” he says. But he worries that Hoel’s measure of information doesn’t distinguish between causation and correlation; as any statistician will tell you, one is not the other. In recent years, computer scientist Judea Pearl of the University of California, Los Angeles, has developed an entire mathematical framework to capture causation. Hoel incorporates some of this work, but Halpern says it would be interesting to apply Pearl’s ideas more thoroughly.

What’s especially interesting about the communications analogy is that a similar analogy comes up in quantum-gravity theories for the origins of space. Error-correcting codes provide some lateral thinking on an idea known as the holographic principle. In a simple example, our three-dimensional space might be generated by a 2-D system (the “film” of the hologram). The contents of 3-D space are smeared over the 2-D system much as a bit of data might be stored in triplicate and dispersed. By looking for the patterns in the 2-D system, you can construct a third dimension of space. Put simply, you could start from the fundamental description of a system, look for structure, and derive a notion of scale and distance, without presuming it at the outset.

The line of thinking based on Integrated Information Theory might also loop back on the mind-body problems that inspired it. Physics and psychology have been at odds since the days of the ancient Greek Atomists. In a world governed by physical law, there seems to be little room for human agency. If you wrestle with whether to eat a cookie, torn between its yumminess and your latest cholesterol report, psychology speaks of conflicting desires, whereas physics accounts for your decision as a chain of atomic motions and collisions. Hoel argues that the real action occurs at the psychological level. Although you could trace the atomic antecedents of all your behavior, a purely atomic explanation would be just that: an explanation of what atoms do. It would say nothing about brains, much less minds. The atomic description has the brain within it, in some highly scrambled form, but to find it, you must strip away the extraneous activity, and that requires some additional understanding that the atomic description lacks. Atoms may flow in and out of your brain cells, their causal relations forming and breaking, yet the mind endures. Its causal relations drive the system.

Emergence is not the only knotty physics subject that Integrated Information Theory might help to untangle. Another is quantum measurement. Quantum theory says an object can exist in a superposition of possibilities. A particle can be both here and there at the same time. Yet we only ever see particles either here or there. If you didn’t know better, you might think the theory had been falsified. What turns the word “and” into “or”? The textbook explanation, or Copenhagen Interpretation, is that the superposition “collapses” when we go to observe the particle. The interpretation draws a line—the so-called Heisenberg cut—between systems that obey quantum laws and observers that follow classical physics. The latter are immune to superposition. In gazing upon a particle that is both here and there, an observer forces it to choose between here or there.

The greatest mystery of quantum mechanics is why anyone ever took Copenhagen seriously. Its proponents never explained what exactly an observation is or how the act of making one would cause a particle to choose among the multiple options open to it. These failings led other physicists and philosophers to seek alternative interpretations that do away with collapse, such as the quantum multiverse. But for the sake of leaving no stone unturned, suppose that Copenhagen is basically right and just needs to be fixed up. Over the years, people have tried to be more explicit about the Heisenberg cut.

Perhaps size defines the cut. Systems that are big enough, contain enough particles, or have enough gravitational energy may cease to be quantum. Because a piece of measuring apparatus satisfies all these criteria, it will collapse any superposition you point it at. How that would happen is still rather mysterious, but at least the idea is specific enough to be tested. Experimenters have been looking for such a threshold and found none so far, but have not completely ruled it out.

Emergence is not the only knotty physics subject that Integrated Information Theory might help to untangle.

But a more direct reading of Copenhagen is that consciousness is the deciding factor, an idea taken up by physicists Fritz London and Edmond Bauer in the 1930s and Eugene Wigner in the ’60s. Because conscious experience, by its very nature, is internally coherent—you always perceive yourself to be in some definite state—the mind doesn’t seem capable of entering into a superposition. It will therefore collapse whatever it apprehends. This conjecture didn’t get very far because no one knew how to quantify the mind, but Integrated Information Theory now provides a way. In 2015 Kobi Kremnizer, a mathematician at Oxford, and André Ranchin, who was a grad student at Imperial College London and has since left academia, explored this possibility in a short paper. Chalmers, at New York University, and Kelvin McQueen, a philosopher of physics at Chapman University, have also taken it up.

In turning to consciousness theory to understand the quantum, these scholars invert the approach taken by physicists such as Roger Penrose who look to quantum theory to understand consciousness. Their proposition is that a brain or brain-like network can enter into a superposition—a state of doublethink in which you perceive the same particle both here and there—but only temporarily. The more interconnected the network is, the faster it will collapse. Experimenters could test this idea by adapting their existing searches for a size threshold. For instance, they might compare two objects of the same size and mass but different degrees of internal interconnectedness—say, a dust mote and a bacterium. If information integration is the key factor, the former can be put into a superposition, but the latter will resist. “Ideally, it would be nice to experiment on nanocomputers which we could program with very large amounts” of integrated information, McQueen says. A bacterium or its cyborg counterpart may not have much of a mind, but it may have enough to qualify as an observer that stands outside the quantum realm.

Integrated Information Theory might also fix another nagging problem with the concept of collapse. It’s one thing to tell you a superposition will collapse, quite another to say what it collapses to. What is the menu of options that a particle will choose from? Is it “here” and “there,” “slow” and “fast,” “mostly here but a little bit there” and “mostly there but a little bit here,” or what? Quantum theory doesn’t say. It treats all possible categories on an equal basis.

The Copenhagen Interpretation holds that the menu is set by your choice of measuring apparatus. If you measure position, the particle will collapse to some position: here or there. If you measure momentum, it will collapse to some momentum: slow or fast. If you measure some quantity too weird to have a name, the particle will oblige. Collapse theories seek to explain how this might work. All measuring instruments are made of the same types of particles, differing only in how they are assembled. So, at the particle level, the collapse process must be the same for all—the menu is fixed at that level. The theories usually assume this fundamental menu is one of positions. Measurements of momentum and other quantities ultimately translate into a measurement of a position, such as where a needle points on a dial. There is no deep reason that position plays this privileged role. The theories assume it just to ensure that they reproduce our observations of a world that consists of spatially localized objects.

The greatest mystery of quantum mechanics is why anyone ever took Copenhagen seriously.

But perhaps some process actively sets the menu. For instance, if collapse is driven by the gravitational field, then it will depend on the positions of masses, which would tend to single out position as the relevant variable. Likewise, if collapse is driven by consciousness, the nature of the mind might dictate the menu. Cosmologist Max Tegmark of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has speculated that the categories might be determined by the structure of thought. The world may be built of separate but interacting parts because our minds, according to Integrated Information Theory, are made in the same way.

Collapse is not just a major unsolved problem in its own right, but a possible window into a level of reality underlying quantum theory. Physicists have suggested that a size threshold could arise from fluctuations of the primitive ingredients out of which space and time emerge. Likewise, if information integration is the culprit, that would presumably reveal something deep. It might connect collapse to the same missing principles that scientists need to understand consciousness. “The immediate goal is self-consistent description,” McQueen says. “But the process of reaching such a goal can often lead unexpectedly to new kinds of explanation.”

The physicists and philosophers I asked to comment on collapse driven by information integration are broadly sympathetic, if only because the other options for explaining (or explaining away) collapse have their own failings. But they worry that Integrated Information Theory is poorly suited to the task. Angelo Bassi, a physicist at the University of Trieste who studies the foundations of quantum mechanics, says that information integration is too abstract a concept. Quantum mechanics deals in the gritty details of where particles are and how fast they’re moving. Relating the two is harder than you might think. Bassi says that Ranchin and Kremnizer use a formula that predicts absurdities such as the instantaneous propagation of signals. “I find it feasible to link the collapse … to consciousness, but in order to do it in a convincing way, I think one needs a definition of consciousness which boils down to configurations of particles in the brain,” he says. In that case, the collapse would be triggered not by consciousness or information integration per se, but by more primitive dynamics that integrated systems are somehow more sensitive to.

Which brings us back to emergence and the biggest emergence problem of all: how the quantity of particles makes the quality of mind. Integrated Information Theory may not solve it—the scientific study of consciousness is young, and it would be surprising if neuroscientists had hit on the right answer so soon. Consciousness is such a deep and pervasive problem that it makes an odd couple of neuroscience and physics. Even if the answer does not lie in the interconnectedness of networks, it surely demands the interconnectedness of disciplines.

George Musser is a writer on physics and cosmology and the author of Spooky Action at a Distance and The Complete Idiot’s Guide to String Theory. He is a contributing editor at Nautilus, and was previously a senior editor at Scientific American for 14 years. He has won the American Institute of Physics Science Writing Award, among others.

This article first appeared online in our “Consciousness” issue in May, 2017.