More than 6,000 feet beneath the surface of the Atlantic Ocean, some 1,400 miles east of Puerto Rico, a remotely operated vehicle skimmed the seafloor, filming a rocky scene almost devoid of life. Perhaps the trail has run cold, thought Julie Huber, an oceanographer at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, as she watched a video feed from land. Her colleagues did the same from a research vessel named Falkor (Too), floating above the ROV.

Then the vehicle’s controllers steered it up a slope. A few squat lobsters scuttled past, seemingly in a hurry to get somewhere. Patches of pale anemones drifted by—another hopeful sign. “And then, bam! We could see this smoke off in the distance,” Huber says. As the ROV inched closer to the crest, a cluster of colossal chimneys rose into view, releasing torrents of black, smoky water. The oceanographers, geologists, and biologists aboard Falkor (Too) cheered: This marked the first discovery in 40 years of an active hydrothermal vent field on this vast section of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

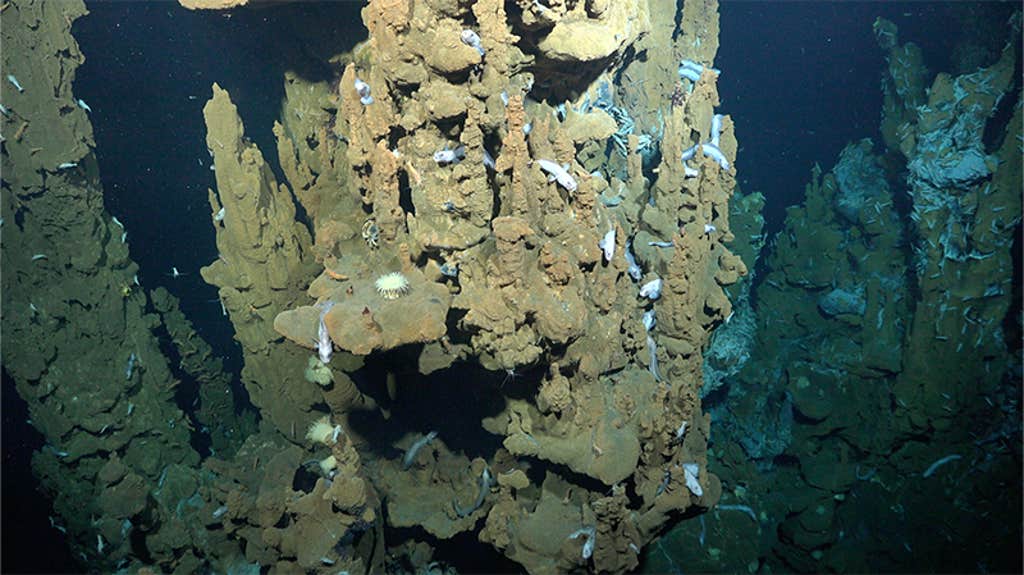

A deep-sea mountain range created by the collision of two tectonic plates, the Mid-Atlantic Ridge owes its existence to the primal energies in Earth’s core, and here they bubble to the surface. Before the ROV’s camera stretched a vibrant metropolis: A vast network of turrets and towers, decorated in strange acid-yellow carpets, was home to ghostly white vent fishes who peered out like suspicious castle-guards. Around them, masses of delicate, lacy sea stars trailed over dense mussel beds, while crabs clothed in shaggy coats reached up to snatch scarlet and white shrimp. These swarmed in the tens of thousands around the chimneys’ volcanic emissions, gorging on something mysterious.

These ingredients provide a banquet for trillions of deep-sea microbes.

Hydrothermal vents are “very spectacular by themselves, but even more when put in the context of the deep sea,” says Joan Alfaro-Lucas, a marine biologist at the University of Victoria in Canada, who joined the expedition. In this otherwise bleak seascape, near-freezing and devoid of sunlight, vents form around hotspots of tectonic activity in the ocean crust, attracting rich communities of marine life that occur nowhere else in the sea.

The discovery came at the start of a 44-day research expedition earlier this year to locate new vents and study their biodiversity on a little-investigated 434-mile long section of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. So remote and uncharted is the landscape that it’s “a bit like going into outer space,” says David Butterfield, a senior research scientist at NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environment Laboratory and expedition lead.

To choose their first exploration site, the team took a cue from decades-old research that had uncovered a large seamount, called Puy des Folles, in the North Atlantic. Those investigations had recorded anomalous temperature and chemistry signals near Puy de Folles, but no sign of active hydrothermal vents; the team on Falkor (Too) wanted to see if they could hunt down the source. Using sonar to map the seafloor, and autonomous vehicles equipped with sensors that could detect telltale heat and chemical cues, they homed in on a spot to release their searching ROV. It followed the trail until they found the spectacular vent field.

Some of the chimneys discovered there reached over 30 feet high. They form when seawater drains into open fissures at active zones in the Earth’s crust; boiling magma cooks the water into a stew with chemicals, metals, and gasses like methane, hydrogen, sulfur, and iron that seep from the molten rock. When this water boils back up and meets the icy ocean, it is released as velvety plumes of smoke—at temperatures reaching 750 degrees Fahrenheit—or precipitates into towering chimneys that carry the unique signatures of Earth’s chemistry below.

Meanwhile these ingredients provide a banquet for trillions of deep-sea microbes. The organisms harvest chemicals and minerals from vent fluids, producing sugar as a byproduct that animals feast on, which they do typically by catching free-floating bacteria in the water column, or by grazing on dense microbial mats that form on the vents’ surfaces. These creatures in turn provide nourishment for others higher up the food chain. “It’s this totally unique ecosystem, driven by volcanic energy,” says Huber.

They discovered deep canyons studded with thousands upon thousands of white anemones.

The abundant swarming shrimp have worked this to their advantage with another feeding approach: They tuck sugar-producing microbes directly into their gills—convenience, with a caveat. To keep their microbial companions fed, they have to get dangerously close to the atomically hot vent plumes. “You could spend hundreds of hours just watching a single shrimp kind of dance the line: close enough so their microbes can get it, but far enough that they don’t get barbecued,” Huber says. “We saw scorched shrimp in lots of places.”

After their first vent field discovery, the Falkor (Too) team ventured onward to new abyssal realms, this time a region called the Kane Fracture Zone that lies about 250 miles north of the Puy des Folles. Between dive sites, the depths provided more marvels: a rare sighting of a Bigfin squid trailing 15-foot-long tentacles; comb jellies who seemed to radiate rainbows; round jellyfish resembling fireworks frozen in time.

The team picked the second site in search of a rare type of hydrothermal vent called a white smoker. This variety has unique chemistry and has been discovered in only a handful of other places, occurring on beds of uplifted mantle rock: Similar geography drew the team to the new location. When they reached it, they sank their equipment to almost 13,000 feet to start the survey—but spent several days exploring an apparently deserted seafloor. “After almost a week, I started to think, ‘Okay, looks like we’re probably not going to find what we’re looking for here,’” says Butterfield.

But then, in a remote corner of the 40-square-mile field they were investigating, a large heat signal bleeped up on the survey equipment. It guided them to a vast field of chimneys; not the white smokers they had been hoping for, but an unexpected array of black smoking vents, staked out by a mosaic of fish, crabs, bright microbial carpets—and the usual crowds of moshing shrimp.

Most surprising to Alfaro-Lucas was the scene at the rocky periphery, where they discovered deep canyons studded with thousands upon thousands of white anemones, like luminous stars. “That was something spectacular, very beautiful to see,” he says. Why some species dominate particular vent sites is, to him, a fascinating question that may point to how the chemistry at each site gives rise to such distinct distributions of life on the seafloor.

After three weeks at sea, the expedition traveled to a site called “Grappe Deux” on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge’s east side. Also almost 13,000 feet deep, in terrain that Huber says “looked like a big landslide had occurred there,” they discovered vent fields besieged by snails, who seemed to guard rocky spires festooned with hundreds of eerie-looking egg capsules. The team also observed a different snail species clinging to the interior of the cauldron-like vents, apparently comfortable with the blistering conditions, as daredevil shrimp tossed themselves in and out of the scorching smoke above. Nearby, bristling pink centipede-like creatures nibbled at the vent surface—a type of deep-sea worm that Alfaro-Lucas suspects may be new to science. “But we really do not know yet,” he says.

Bristling pink centipede-like creatures nibbled at the vent surface.

Answering such questions will be a focus in the years of analysis that lie ahead, drawing on hundreds of chemical, microbial, and animal samples gathered during the expedition. Knowing the chemistry of individual sites could help decipher the precise mix of microbes that powers the endemic life at each one. “Each vent field could be unique,” Huber says. “When you think about biodiversity on our planet, they’re pretty remarkable that way.”

All known active deep-sea vents on Earth would fill an area of just 20 square miles—less space than the island of Manhattan, says Eva Ramirez-Llodra, a marine ecologist and science coordinator at the ocean research non-profit Rev Ocean, who was not involved in the expedition. This puts the recent revelations into context. “Every single discovery is significant,” she says.

The expedition’s data may also help illuminate how hydrothermal vents connect to each other—even the fascinating possibility that they form connected habitats along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge that animals move between. This invites larger questions about the vulnerability of individual sites and the potential ripple effects of destroying one, a possibility that looms large with the specter of deep-sea mining.

That prospect only increases the urgency for the researchers, who estimate that the expedition laid the foundation for at least 20 years more research at the new sites, with an ocean of discoveries yet to be made. In the deep sea, says Butterfield, “you never run out of questions.” ![]()

Lead Image courtesy of The Schmidt Ocean Institute