It’s pretty obvious that dogs have sharper ears and cats a keener sense of smell than we do. But as powerful these senses are, they are merely keener versions of the ones we humans possess. The animal kingdom also boast some senses that are arguably more impressive—senses that are far more exotic than our pets’, and that seem unfathomable to the human brain. From electric fields to infrared radiation, here are some of the most bizarre ways animals perceive our world.

Elephants communicate seismically

With their great, big ears, it’s no surprise that elephants have an especially keen sense of hearing. What’s less expected is that some of their sonic communication goes not through the air but through the ground. Elephants can make very low-frequency vocalizations—too low for the human ear to catch—that vibrate through soil for miles. In one experiment, Stanford biologist Caitlin O’Connell-Rodwell transmitted recorded “danger” calls through the ground to a group of elephants, who immediately starting acting nervously. But they didn’t react to gibberish ground rumblings that she produced. The physical structure of an elephant’s foot, such as thick pads of fat inside, may help transmit those ground vibrations up to the ear.

Bumblebees sense the electric fields of flowers

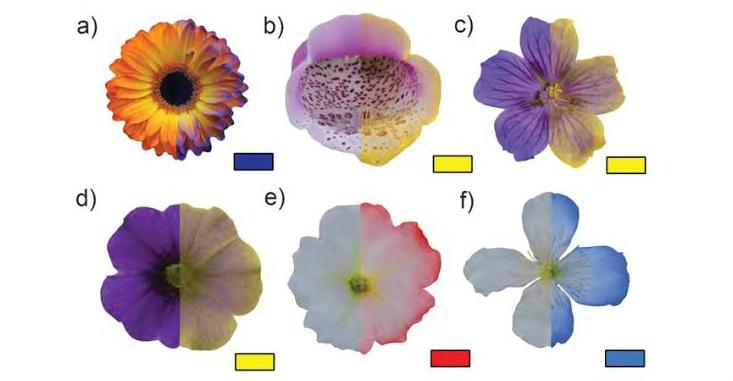

For years scientists have known that a handful of aquatic creatures—including electric eels, platypuses, and sharks—can sense electric fields generated by the twitching nerves and muscles of their prey. But then came a more surprising discovery: Bumblebees also can use electric fields to find food: The bees usually carry a positive charge, and they can pick up on the slightly negative natural charge of most flowers. (The opposite potentials also help pollen stick to the insects.) The bees even seem to distinguish between the differently shaped electric fields produced by various flowers. We humans can appreciate flowers for their beauty, but without a bee’s ultraviolet vision, keen smell, and electric sense, we can’t really experience flowers in their full glory.

Dung beetles orient themselves by the light of the Milky Way

Dung beetles do not have great vision. They cannot pick out individual stars or constellations in the night sky. But one particular species that lives in the South African grasslands can, even with its weak beetle eyes, see the bright stripe across the sky that is the Milky Way. According to an experiment replicating these conditions in a planetarium, this dung beetle seems to use the Milky Way as a reference so it can roll fresh dung in a straight line. (Moving in a straight line without any visual cues is, in fact, pretty hard for any creature.)

Animals senses are often remarkable because they exceed the boundaries of human perception, but sometimes, they just as remarkable for how limited they can be and still be perfectly suited to their purpose.

Birds navigate using magnetic fields

Birds routinely migrate over thousands of miles, maintaining their courses even on overcast days without the Sun or stars for guidance. Instead they rely on an internal magnetic compass. How exactly birds sense the earth’s magnetic field, however, is an enduring scientific mystery. Currently there are two main hypotheses. In the first, birds may use specialized cells in the ear or beak that contain a magnetic iron compound appropriately called magnetite. (The exact cells have, however, have never been identified in birds.)

The second and more complicated hypothesis involves quantum mechanics. When light hits a protein called cryptochrome in a bird’s eye, it creates unpaired electrons that are sensitive to magnetic fields. And according to quantum mechanics, “entangled” electrons can interact to provide information on the magnetic field. Whether birds see, hear, or feel the magnetic field is still up for debate, but it’s clear that they do somehow sense it.

Snakes find their prey by sensing heat

A mouse can hide or stay quiet, but it cannot stop heat from radiating out of its furry little body. And unfortunately for warm-blooded mice, snakes have specialized organs just for detecting heat. Pitvipers, pythons, and boas have all independently evolved pit organs on each side of their faces. These organs contain cells that are exquisitely sensitive to heat, sensitive enough to detect the warmth of a small rodent one meter away. That’s how snakes can hunt so effectively at night. Even a blind snake without working eyes but with pit organs intact is about as good as a normal snake. (Visit “How Animals See the World” to get a great demonstration of snakes’ infrared vision.)

Sarah Zhang is a staff writer at Gizmodo.