After a cat loses its last aesthetic and behavioral traits characteristic of a kitten, it also loses much of its appeal as a companion to some people. At the same time, this cat may begin going into heat, agitating itself in a way that is both embarrassing and unsettling. With the human’s affection wearing thin, the cat might gaze longingly out the window. Sensing an opportunity for everyone to get what he or she desires, this frustrated pet owner might then crack the window open. If the cat is not spayed or neutered it will be tempted to jump out the window in search of reproductive opportunities.

It happens more than you might think. The neighborhoods surrounding college campuses, for example, are notorious for the explosion in the population of one- year-old, unfixed cats that start to scavenge from Dumpsters just after the last exams in the spring. As the warmer months tend to be the most prolific for mating, this population quickly skyrockets. While these cats suffer, they also successfully hunt a huge number of other creatures. As a result, these events precipitate an attending debate over the role of feral cats within the natural and cultural landscape.

This debate takes place between those who are concerned with the welfare of individual animals and those who prioritize the protection of biological diversity. Each group agrees that the natural world is out of alignment, and that this disharmony is eroding the richness of the natural world. The debate over what should be done pivots around different views regarding which lives are important (and, conversely, which deaths tragic), where humans’ obligations lay, and what sort of future is desirable.

For some, feral cats are a result of human neglect, deserving of specific rights. In this estimation, the cats’ potential to live satisfying lives has been wasted by humans. In order to ameliorate this wrong, thoughtful action must be taken. In the United States, those sympathetic to the welfare of feral cats support a program that aims to humanely trap them, surgically sterilize them, and return them to the place they originally inhabited. Those who support this program believe that populations will slowly but steadily decline due to these limits on the reproductive capacities of feral cats. These animals live sorrowful lives, often starved and sick, they say, and it will be ethically productive for their population to be reduced, if done humanely.

To others, feral cats are unnatural predators that upend local ecologies. As an introduced species in North America, they have an unfair advantage over their prey. Indeed, a recent study suggests that in the United States, outdoor cats kill as many as 3.7 billion other creatures annually. Many of these prey animals are not eaten by their killers—they’re wasted, left to rot on lawns, streets, and doormats. The fact that many cats’ diets are subsidized by people only further tips the scales in their favor, disrupting the balance established by the glacial force of evolutionary history. With few natural predators, say cat critics, it is up to humans to limit the population of feral cats by any means necessary, including widespread euthanization. Future actions must counter past wrongs, and that means negating the impacts of feral cats on the local ecosystem—a problem we caused in the first place.

Despite the passion on both sides of this debate, the issue is most likely intractable. There are as many as 50 million feral cats spread across the United States. Because their geographic range is so vast, it would be nearly impossible for all of them to be sterilized or euthanized. The more realistic governments and conservation biologists addressing the threat posed by feral cats choose to concentrate their efforts on critical and isolated sites.

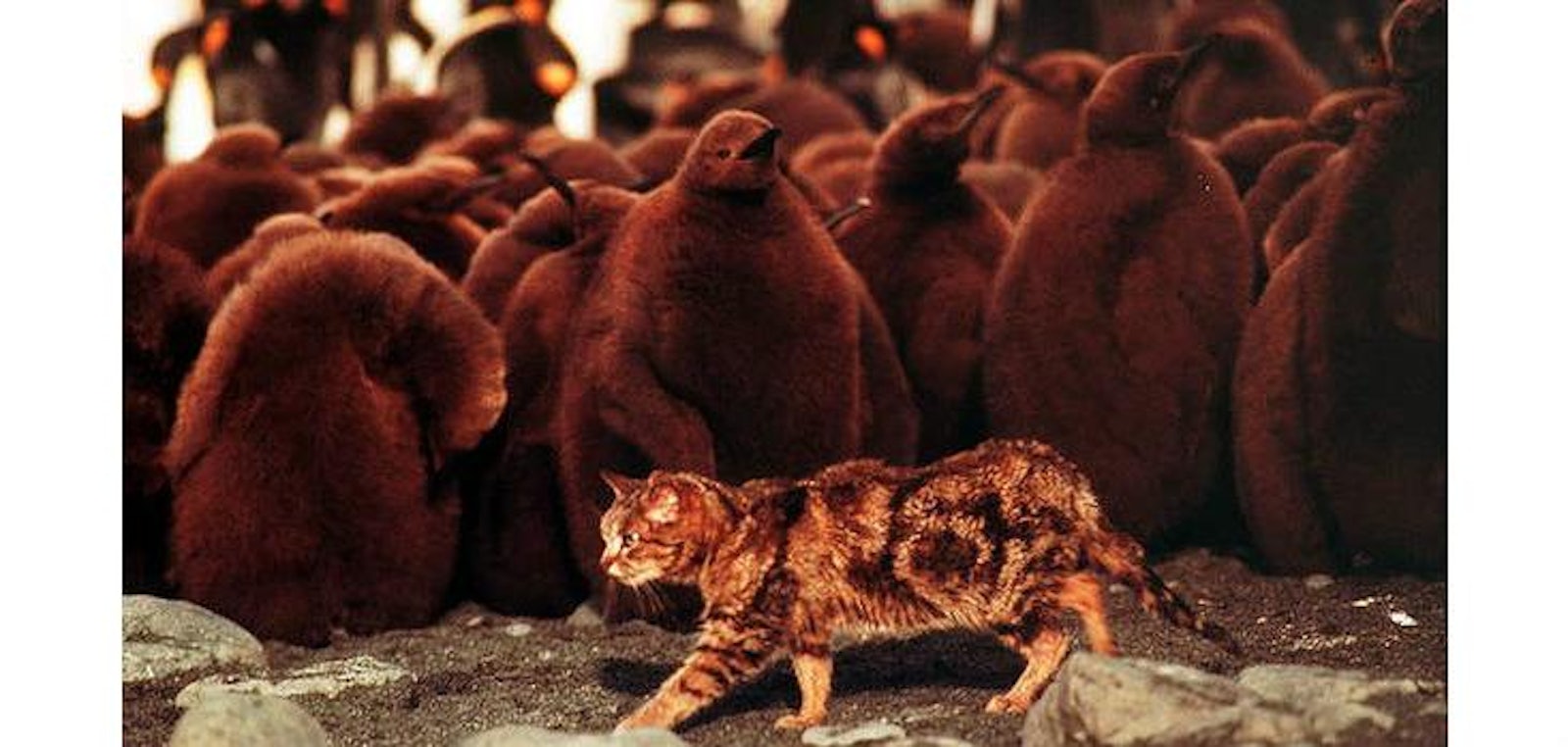

On Macquarie Island, a UNESCO Ecological World Heritage site and a vital habitat for avian migrations in the Southern Hemisphere, the Australian government sought to eradicate the feral cats that were imperiling the seasonal bird population. Because it was a small island, this was an achievable goal, accomplished with targeted poisons, traps, and dog-led hunts in the last years of the 20th century. After that, however, rabbit populations ballooned, leading to unintended consequences. The growing rabbit population devastated local vegetation, increasing erosion, causing problems for the penguins that roost there. A second eradication, this time aimed at rabbits, has been thus far successful, thanks again to a significant government investment and the confined nature of the problem.

Nature has many stories, and these are only a few. Still, the challenging lesson to take from these events is that the living world is devilishly complicated, and very difficult to predict or control. We look out at the world and have high hopes for preserving what we think has value, but it is hubris to expect we will usually be successful.

Charlie Nichols studied studio arts before turning his attention to cultural anthropology. As a graduate student, he studies the politics of wildlife management and the social impacts of extinction.