Here’s a riddle. We’ve never seen any, and we don’t know if they exist, but we think about them, debate them, and shout at each other about them. What are they?

Aliens, of course.

A while ago I wrote a piece for Nautilus on what might happen to us after learning about the existence of extraterrestrial life—whether microbes on Mars or technological civilizations around other stars—and asked if there might be inherent, unexpected, dangers in acquiring this information. Could infectious alien memes run riot, disrupting societies? Might intelligent life decide to shield itself from such knowledge? It was a whimsical, quizzical thought experiment, exploring the real science of our hunt for life in the cosmos, and the possibility—even if remote—that there could be unexpected perils for intelligently curious life anywhere.

Simple enough. But as comments to the piece began to pile up—many in my inbox—I found myself on the receiving end of a barrage of opinion. There was outrage at the suggestion that there might ever be circumstances to drive us (or any intelligent species) to close our astronomical and scientific eyes to avoid picking up dangerous alien data. At the other extreme, and I do mean extreme, there was outrage that we were already being kept in the dark about aliens by our governments. And across the board was a world-weary sense of our seemingly boundless capacity to screw things up, big universe or not.

Phew.

The possibility of life somewhere else in the cosmos isn’t just scientifically fascinating, it’s a unique mental playground for our hopes, fears, and fantasies. It can also be, as I’ve learned, an inkblot test; a reflection of our inner thoughts, emotions, and—to be honest—hang-ups.

Science is littered with the corpses of phenomena we’d thought we’d observed in their entirety.

For some of us, the prospect of joining a universe that we fantasize is populated by intelligent aliens à la Star Wars is irresistible. It’s an escape hatch from the ever-diminishing circles of an Earth with 7 billion hungry, polluting humans. We have to stretch our interstellar wings. For others, a sinister extraterrestrial presence already exists here on Earth, a scapegoat for explaining humanity’s ills—so there’s no point seeking aliens out there when they’re already down here, locked behind a firewall of deceit and cat videos.

One can feel a modicum of sympathy for these views. But what bothered me the most were statements of defeat; “There’s no point worrying. We know there’s nothing out there.” These stem from the fact that we currently have no answer to the “Where is everybody?” question, also known as the Fermi Paradox: If life is reasonably likely, and the universe is vast and old, why are extraterrestrials not already on our doorstep? Many people construe this as evidence that intelligent, technological life must be thinly spread through cosmic space and time, out of sight, out of the equation. True? No, not necessarily.

Despite our best efforts, science is littered with the corpses of phenomena we’d thought we’d observed in their entirety. Consider the planet Mercury. Since the 1880s scientists generally assumed that Mercury was tidally locked to the sun, with a day length equal to its orbital period of 88 Earth days. Astronomers’ hand-drawn maps nicely corroborated this, always showing the same surface features on a permanently sunlit side.

Except that’s wrong. Data in the mid 1960s revealed that Mercury spins once every 59 days—despite what had been charted across the decades. In fact, the maps were consistent with our view of Mercury every second orbit, when it was easier to observe the surface from the Earth’s northern latitudes—we simply didn’t appreciate how blinded we were.

Time and again we grossly overestimate our ability to sense what’s happening in the universe around us. Unlike many Hollywood movies, there is no global “command center” that magically monitors and charts our interplanetary turf, alerting presidents, prime ministers, and plucky school kids that it’s time to welcome our alien overlords.

For example, until the 1990s we hadn’t discovered any of the substantial trans-Neptunian objects that share Pluto’s heritage in the distant Kuiper Belt. It’s true that we’ve now detected over 1,500 of these bodies, the largest of which are over a thousand kilometers across. But there should be another 100,000 of these objects—we just haven’t found them yet because they’re so faint.

Consider too that the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope—a sky charting behemoth currently under construction—will take 10 years to detect 90 percent of all potentially hazardous (to us) asteroid and comet bodies larger than about 140 meters. It’ll be a remarkable accomplishment, yet the missing 10 percent likely totals 2,000 objects. That’s a lot of critical stuff that we simply can’t find in our own solar system. This doesn’t mean that there are alien spacecraft or artifacts floating around our neighborhood, but if there were, there’s no guarantee we’d have spotted them.

We’ve similarly only scraped the surface when it comes to trying to detect artificial radio signals or modulated flashes of light traversing the cosmos. Despite the noble and sophisticated efforts of a cadre of scientists working on SETI—the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence—over the past several decades, the window of opportunity has been microscopic in cosmic terms.

Many forms of SETI could be a bargain.

NASA’s Curiosity rover recently sniffed a burst of methane on Mars, which may prove to be a breakthrough—a sign of extraterrestrial biology right under our nose. But that’s a handful of data points from a mission that’ll traverse a tiny fraction of a 56 million square mile planetary surface. This is not yet anything more than a tentative assay.

We should, as I argued in Nautilus in September, be cautious in the face of this ignorance. As speculative as it is to consider infectious extraterrestrial memes, we simply don’t know what we’ll find. The cost of being prudent, to at least consider the implications, is small, and needn’t stop the search.

But, right now, the cost of that search is steep. The Curiosity rover has a $2.5 billion price tag. NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, due to launch in 2018, has a shot at sensing atmospheric molecules like carbon dioxide, methane, and water in a few Earth-analog planets orbiting nearby stars—molecules that can participate in biogeochemical cycles. It costs $9 billion. Huge, 30-meter aperture earthbound telescopes are being built that will have a similar capability, perhaps even sniffing out molecular oxygen in atmospheres 100 trillion miles away. These come in at around $1 billion a pop.

The successful detection of these bio-signatures would be extraordinary, and would bolster our hopes that life can be studied remotely in a future filled with astronomical sensors. Except it’s going to be awfully hard work, very expensive, and the first measurements will be rudimentary at best.

Many forms of SETI, by contrast, could be a bargain. Early expectations of stray radio signals leaking from technological civilizations were overly optimistic—we ourselves have gone radio faint with digitization. But the recent surge of exoplanet discoveries has provided very specific targets. The problem is that observatories able to pursue these targets, like the Allen Telescope Array in northern California, have struggled with on-again, off-again funding. For this project, a couple of million dollars is all that stands between action and inaction for a year.

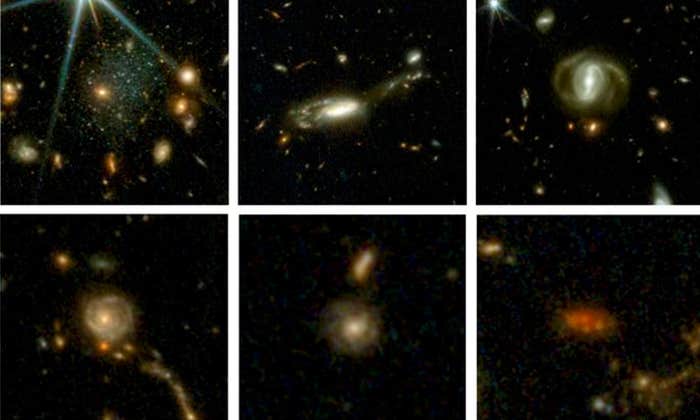

New efforts to hunt for extraterrestrial techno-signatures are also bubbling up from the scientific community: From seeking peculiar stellar eclipses, to optical surveys of transient events, or sensing the infrared glow of waste heat that might emanate from alien structures.

One can be skeptical, but the simple fact remains that only SETI has the potential to answer all of our questions in one fell swoop: Is there other life? Is it intelligent? I think that this potential raises SETI’s reward/failure ratio to on par with billion-dollar projects and what their bio-signature measurements can, and can’t, confirm for us.

On balance, it’s time to make a bold new effort at SETI, to pick up the gauntlet thrown by pessimism and our continuing ignorance. That’s right, let’s stick our necks out and risk those alien memes anyway, I’m tired of prehensile thumb twiddling.

Caleb Scharf is an astrophysicist and the Director of Astrobiology at Columbia University in New York. His latest book is The Copernicus Complex: Our Cosmic Significance in a Universe of Planets and Probabilities.