Several years ago, particle physicist Lily Asquith was hanging out with a few musician pals in London after a band rehearsal, doing impromptu impersonations of what she thought the various elementary particles might sound like, and encouraging the drummer to recreate them electronically. Another band member asked if it would be possible to create sounds based on actual data from an accelerator, and the LHCsound project was born.

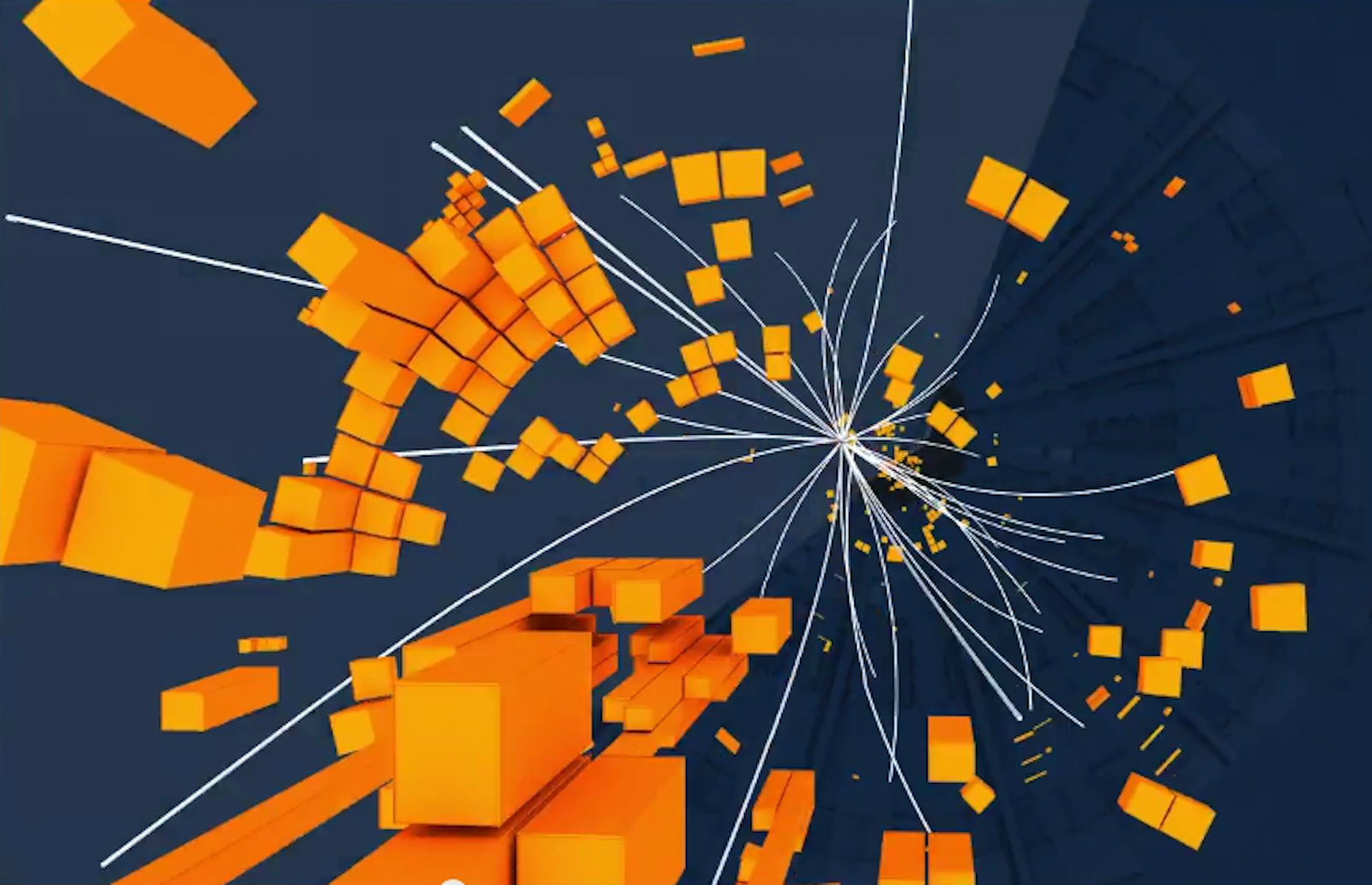

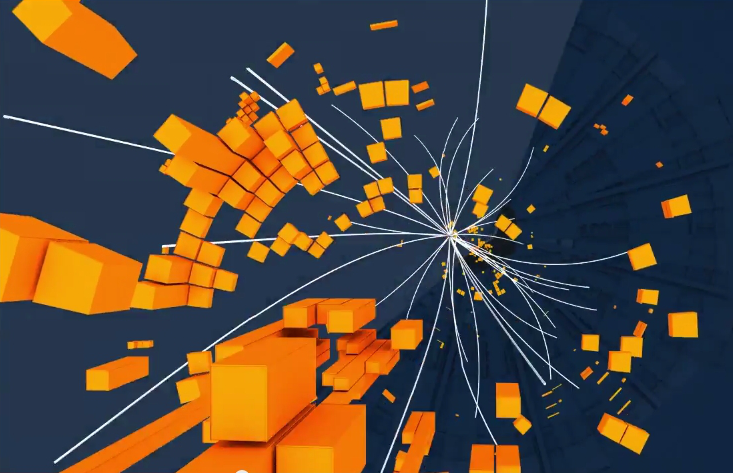

LHCsound is a collaboration of physicists, musicians, and artists dedicated to transform data from the ATLAS detector at the Large Hadron Collider into music via a process called sonification. She uses a technique called parameter mapping, in which various properties of sound are matched to properties of the physical data: For example, pitch would correlate with speed, volume would correlate with direction, and duration (time) would correlate with distance. Just listening to the sound of a coin rolling across a tabletop won’t necessarily tell you anything interesting about its motion. Sonification, on the other hand, creates a new sound that “contains more information than just listening to the coin or just watching it can tell me,” Asquith explained on the LHCsound blog.

The sounds compiled so far—including the Higgs boson and simulations of hypothetical supersymmetric particles—don’t much sound like music on their own, but participating musicians are incorporating them into their compositions.

Asquith and her colleagues aren’t the first to think about translating scientific data into sound: It’s been done with data from Fermilab’s particle colliders, for Saturn’s rings, for the Northern Lights, for seismic data and computing networks, and even for the River Thames (as it flows past the birthplace of LHCSound), to name a few. It’s become a common feature of science-and-art multimedia collaborations.

But Asquith hopes sonification will eventually transcend being a purely aesthetic achievement and prove to be a useful tool for actual data analysis, revealing new patterns by augmenting the colorful visual representations of data currently produced by particle colliders. There’s certainly a scientific precedent in the optical regime: Astronomers can pick up on different aspects of celestial features when they are viewed in visible, infrared, X-ray, or ultraviolet regimes, and these different filters have led to significant breakthroughs over the decades. For instance, combining optical and X-ray images clearly showed the relative distribution of regular matter and dark matter in the so-called Bullet Cluster—actually two galaxy clusters colliding—back in 2006.

Asquith has compared the basic concept of using sound to search for interesting signatures to a heart monitor that translates the electrical activity of the heart into audible beeps; hospital personnel can hear when the heart rate slows, speeds up, or becomes erratic without looking at the visual representation of that activity, while doing something else entirely. Why couldn’t you create a similar device to monitor how collider data changes over time, using your ears rather than your eyes to detect small fluctuations in, say, pitch? “Our ears are sophisticated detectors,” she told New Scientist back in 2010, capable of locating both the source and location of sounds relative to each other, along with subtle shifts in pitch or tempo, although the human ear is less adept at distinguishing fluctuations in volume, however.

Right now, the library of sounds collected by the LHCsound project hasn’t yielded much in the way of revolutionary scientific insights, but her approach is still in its infancy—by the standards of scientific progress—so she remains hopeful that this could change. In the meantime, the collaboration continues to flourish artistically, a wonderful merging of music and physics that helps non-scientists better appreciate the aesthetics of science, and the patterns that might be lurking just beyond our ken.

Jennifer Ouellette is a science writer and the author of The Calculus Diaries and the forthcoming Me, Myself and Why: Searching for the Science of Self. Follow her on Twitter @JenLucPiquant.