At the height of his powers in 15th century Florence, Lorenzo de Medici managed to secure a magnificent giraffe for his menagerie. The animal was such a marvel that several works of art depicted its arrival. (Just how grueling and gruesome the transit must have been to the giraffe is lost to history.) For ages, private menageries were the way that people in cities—the upper classes, that is—could see wild animals. Eventually, though, as empires fell, private menageries evolved into municipal zoos, allowing the public, notably children, to marvel at monkeys, creepy crawlies, and lions.

Today, though, zoos are imagined somewhat less positively. Some think that to hold animals captive, for spectacle, can be dangerous and cruel. Which raises the question—can the love of zoos be balanced with the needs of animals? This was the conundrum facing world-renowned architect Bernard Tschumi when, right after working on Athens’ New Acropolis Museum, he accepted a contract to redesign the crumbling Paris Zoological Park in 2003. Built in 1934, the Park “was different” from its contemporaries, said Tschumi. “It was an artificial landscape for the animals to live within, but without theater, which was quite novel for the time. It was not a circus.”

A zoo is simultaneously a hospital, a gigantic restaurant, a spectacle, and a high security precinct.

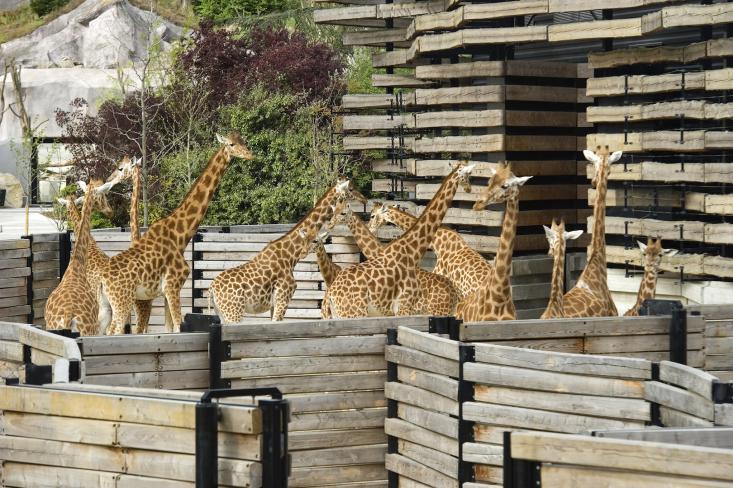

Tschumi and his team spent five years reconstructing the zoo, which reopened to the public in 2014. Working around the resident herd of giraffes (they were too hard to move), he sought to incorporate the zoo’s history, the changing ethical considerations of animal conservation, and his style—a minimalistic, almost industrial aesthetic—in his structural revision. “It was to be as simple as possible, as truthful as possible,” he said. Nautilus sat down with Tschumi at his Manhattan studio, surrounded by boxed models bound for a new showing of his recent retrospective at the Centre Pompidou, to talk about the zoo and how it reflects the changing narrative of conservation science.

What was your initial strategy for the zoo’s redesign?

We decided to develop an entirely new strategy for the zoo, which was not about display of species, but the recreation of a series of so-called “biozones,” which correspond to geographic and climate conditions, whether it is the Sahara Desert or the ice of the Patagonia landscape. Most of this is achieved through the routes. The zoo is relatively small, but because the routes are meandering, you have the feeling the zoo is much larger. The meandering paths allow you to define animal habitats as well. So you have the defined place of spectacle that is also a place of movement. In other words, architecture was there to be a background to the landscape, as opposed to the landscape being a background to architecture.

How did the requirements of the zoo inform your design?

There are some artifacts that you cannot avoid when you are designing a zoo. I would divide these into three categories. First, aviaries. Second, tropical greenhouse. And the third is related to the fact that a zoo is actually a very technical building. It is simultaneously a hospital, a gigantic restaurant, a spectacle, and in a way, a high security precinct. I use the word “precinct,” rather than prison, because that high security goes both ways; you have to protect the zookeepers, public, and the animals—a complex give and take. We worked with biologists and animal specialists on site. This was not something that we could invent or guess. Animals have to feel relatively protected. They have times they want to be out of view. For some, we used some tricks, like the lion had a big rock that was heated and so it would rest on the heated rock in full view of the public.

Was there a design challenge that fascinated you the most?

Probably the most interesting part, for these technical spaces alongside the animals, is something that I have used in other projects, called the Double Envelope Principle. This means that, from the outside, the building seems to be very integrated in the landscape itself, but in reality behind this facade is something that you hardly see. For example, look behind the wooden boards of the giraffe house, you see it is really a metal building under there. The outer envelope is really playing with the sensibility of nature. It is really beautiful how the wood was first this burnished orange color, but then when it ages it becomes this neutral color, which works well with the artificial rocks from the early days. The relationship of the animal to the wood seemed to me more, dare I say, “natural.”

“You realize these giraffes have been in the zoo for five or six generations? You can’t send them back.”

Did you attempt to mimic nature in your design?

You don’t find aviaries in the jungle. They are functional requirements, but turned into poetic environments. At no moment did we want to impose the architecture as architecture. I tried very much to avoid this, and use fairly simple devices like the protection of the wood beams as something that keeps the sympathetic character of the environment while performing a function.

Did you have reservations about preserving something that keeps animals out of their natural habitat?

In some ways, this is a very difficult thing to say, because you think about these 19th century explorers who were taking artifacts from Mesopotamia, from Egypt, or from Greece. They said it was for preservation and protection, too. So I had, at first, a sort of instinctive reaction to feel the same about these animals. But then when I mentioned it to the zookeepers, they said, “You realize these giraffes have been in the zoo for five or six generations? You can’t send them back.” So, in a number of cases this is not at all about taking them away from their environment. It is about protecting certain species where, in their own environment, they would not survive. It is a very different perspective.

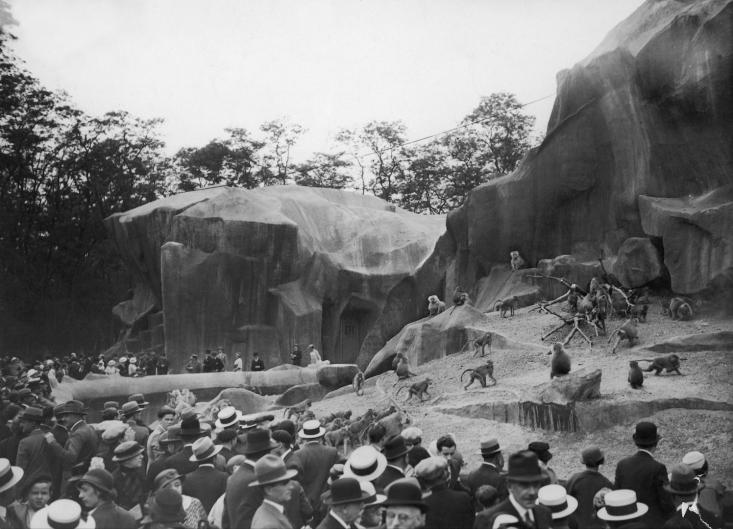

How was it to revisit the zoo as the designer so many years after having gone there as a child?

Actually it was one of my regrets: the old zoo had a very huge rock, which they called the Rock of Monkeys. It was in such bad condition that we had to take it down. So now the monkeys are in a slightly different environment. But then, I am not a zoo specialist. As the architect, it is about being creative, not being clichéd. Not being caught into the received ideas of what a zoo should look like or a factory should look like. That I find very stimulating.

Claire Cameron is Nautilus’ social media & news editor. Follow her on Twitter @clarabell8.