Earth is most fortunate to have vast webs of magnetic fields surrounding it. Without them, much of our atmosphere would have been gradually torn away by powerful solar winds long ago, making it unlikely that anything like us would be here.

Scientists know that Mars once supported prominent magnetic fields as well, most likely in the early period of its history when the planet was consequently warmer and much wetter. Very little of them is left, and the planet is frigid and desiccated. These understandings lead to an interesting question: If Mars had a functioning magnetosphere to protect it from those solar winds, could it once again develop a thicker atmosphere, warmer climate, and liquid surface water?

James Green, director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division, thinks it could. And perhaps with our help, such changes could occur within a human, rather than an astronomical, time frame.

In a talk at the NASA Planetary Science Vision 2050 Workshop at the agency’s headquarters, Green presented simulations, models, and early thinking about how a Martian magnetic field might be re-constituted and how the climate on Mars could then become more friendly for human exploration and, perhaps, communities.

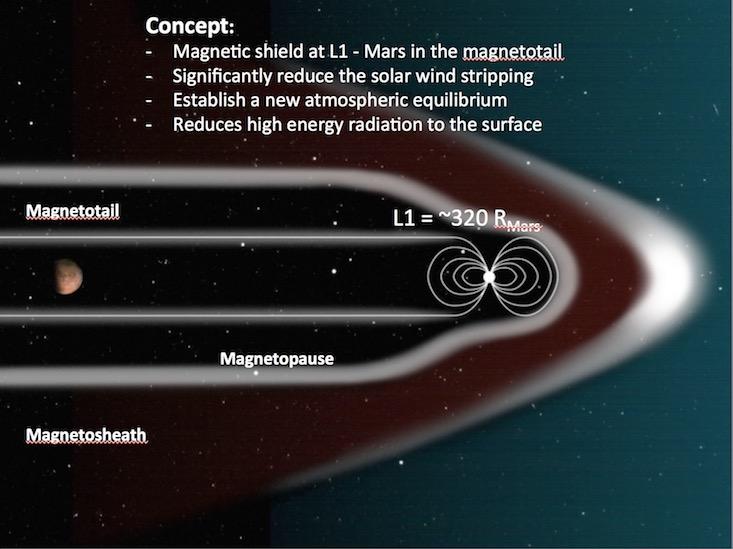

It consisted of creating a “magnetic shield” to protect the planet from those high-energy solar particles. The shield structure would consist of a large dipole—a closed electric circuit powerful enough to generate an artificial magnetic field. Simulations showed that a shield of this sort would leave Mars in the relatively protected magnetotail of the magnetic field created by the object. A potential result: an end to large-scale stripping of the Martian atmosphere by the solar wind, and a significant change in climate.

“The solar system is ours, let’s take it,” Green told the workshop. “And that, of course, includes Mars. But for humans to be able to explore Mars, together with us doing science, we need a better environment.”

Is this “terraforming,” the process by which humans make Mars more suitable for human habitation? That’s an intriguing but controversial idea that has been around for decades, and Green was wary of embracing it fully.

“My understanding of terraforming is the deliberate addition, by humans, of directly adding gases to the atmosphere on a planetary scale,” he wrote in an email. “I may be splitting hairs here, but nothing is introduced to the atmosphere in my simulations that Mars doesn’t create itself. In effect, this concept simply accelerates a natural process that would most likely occur over a much longer period of time.”

What he is referring to here is that many experts believe Mars will be a lot warmer in the future, and will have a much thicker atmosphere, whatever humans do. On its own, however, the process will take a very long time.

A relatively small change in atmospheric pressure can stop an astronaut’s blood from boiling.

To explain further, first a little Mars history.

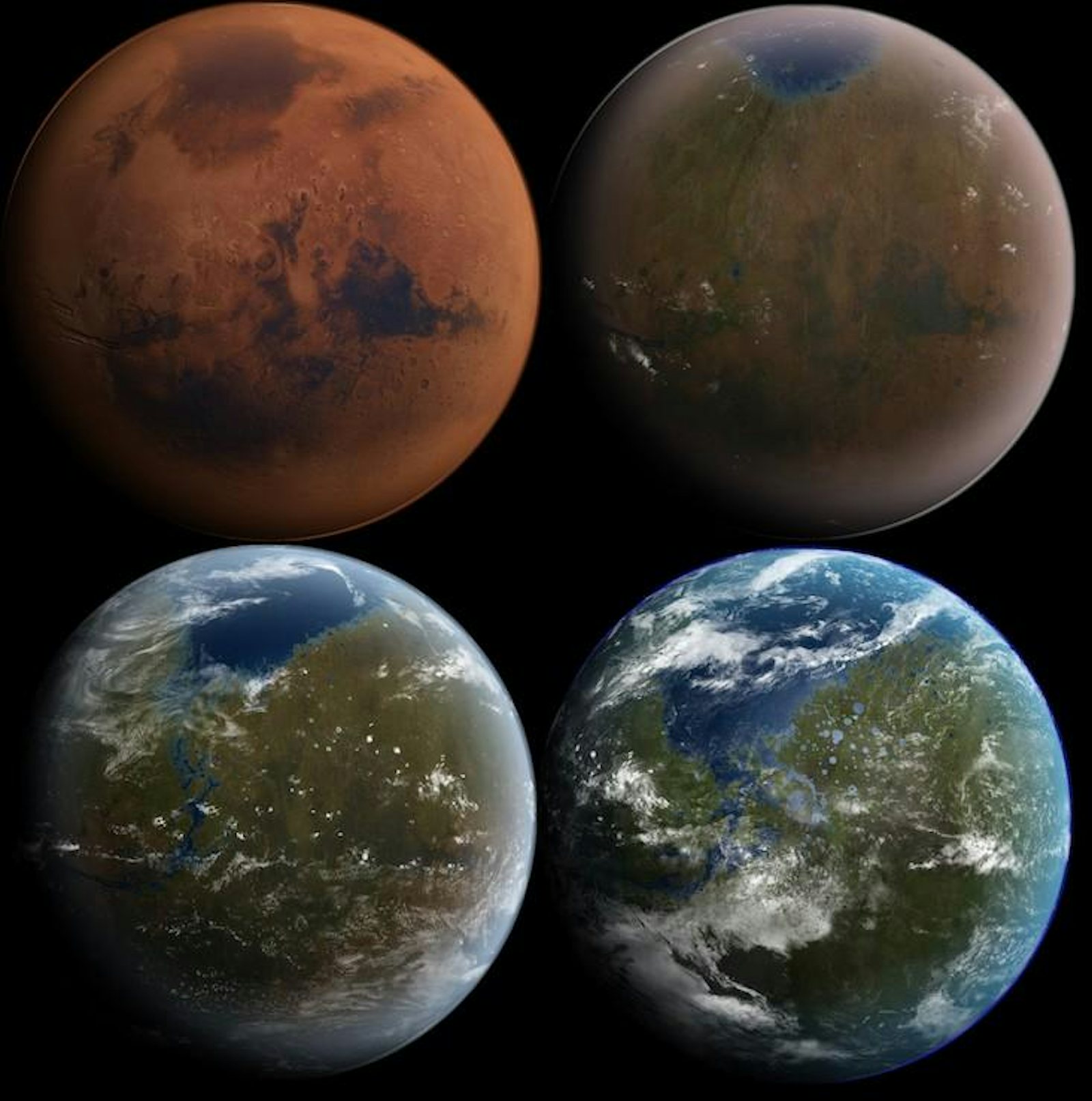

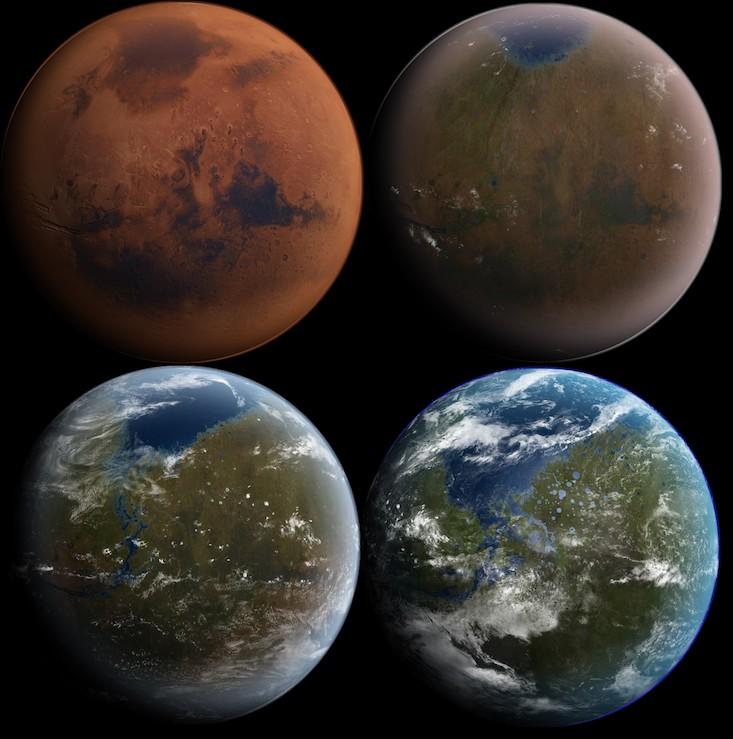

More than 3.5 billion years ago, Mars had a much thicker atmosphere that kept the surface temperatures moderate enough to allow for substantial amounts of surface water to flow, pool, and perhaps even form an ocean. (And who knows, maybe even for life to begin.) But since the magnetic field of Mars fell apart after its iron inner core was somehow undone, about 90 percent of the Martian atmosphere was stripped away by charged particles in that solar wind, which can reach speeds of 250 to 750 kilometers per second.

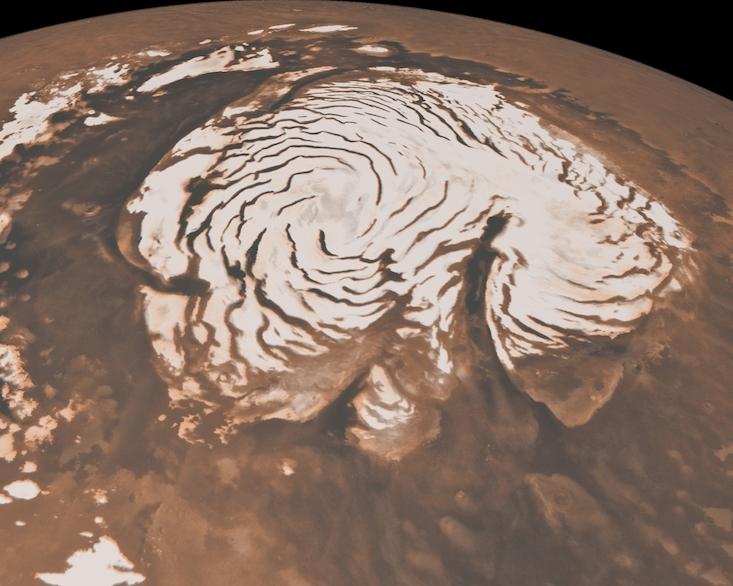

Mars, of course, is frigid and dry now, but Green said the dynamics of the solar system point to a time when the planet will warm up again. He said that scientists expect the gradually increasing heat of the sun will warm the planet sufficiently to release the covering of frozen carbon dioxide at the north pole, will start water ice to flow, and will in time create something of a greenhouse atmosphere. But the process is expected to take some 700 million years.

“The key to my idea is that we now know that Mars lost its magnetic field long ago, the solar wind has been stripping off the atmosphere (in particular the oxygen) ever since, and the solar wind is in some kind of equilibrium with the outgassing at Mars,” Green said. (Outgassing is the release of gaseous compounds from beneath the planet’s surface.) “If we significantly reduce the stripping, a new, higher pressure atmosphere will evolve over time. The increase in pressure causes an increase in temperature. We have not calculated exactly what the new equilibrium will be and how long it will take.”

The reason why is that Green and his colleagues found that they needed to add some additional physics to the atmospheric model, dynamics that will become more important and clear over time. But he is confident those physics will be developed. He also said that the European Space Agency’s Trace Gas Orbiter now circling Mars should be able to identify molecules and compounds that could play a significant role in a changing Mars atmosphere.

So based on those new magnetic field models and projections about the future climate of Mars, when might it be sufficiently changed to become significantly more human friendly?

In the simulation, the magnetic field is about 1.6 times strong than that of Earth.

Well, a relatively small change in atmospheric pressure can stop an astronaut’s blood from boiling, and so protective suits and clothes would be simpler to design. But the average daily range in temperature on Mars now is 170 degrees Fahrenheit, and it will take some substantial atmospheric modification to make that more congenial.

Green’s workshop focused on what might be possible in the mid-21st century, so he hopes for some progress in this arena by then.

One of many intriguing aspects of the paper is its part in an NASA effort to link fundamental models together for everything from predicting global climate to space weather on Mars. The modeling of a potential artificial magnetosphere for Mars relied, for instance, on work done by NASA heliophysics—the quite advanced study of our own sun.

Chuanfei Dong, an expert on space weather at Mars, is a co-author on the paper and did much of the modeling work. He is now a postdoc at Princeton University, where he is supported by NASA. He used the Block-Adaptive-Tree Solar-Wind Roe-Type Upwind Scheme (BATS-R-US) model to test the potential shielding effect of an artificial magnetosphere, and found that it was substantial when the magnetic field created was sufficiently strong. Substantial enough, in fact, to greatly limit the loss of Martian atmosphere due to the solar wind. As he explained, the artificial dipole magnetic field has to rotate to prevent the dayside reconnection, which in turn prevents the nightside reconnection as well.

If the artificial magnetic field does not block the solar winds properly, Mars could lose more of its atmosphere. That’s why the planet needs to be safely within the magnetotail of the artificial magnetosphere.

In their paper, the authors acknowledge that the plan for an artificial Martian magnetosphere may sound “fanciful,” but they say that emerging research is starting to show that a miniature magnetsphere can be used to protect humans and spacecraft. In the future, they say, it is quite possible that an inflatable structure can generate a magnetic dipole field at a level of perhaps 1 or 2 Tesla (a unit that measures the strength of a magnetic field) as an active shield against the solar wind. In the simulation, the magnetic field is about 1.6 times strong than that of Earth.

As a summary of what Green and others are thinking, here is the “results” section of the short paper:

“It has been determined that an average change in the temperature of Mars of about 4 degrees C will provide enough temperature to melt the CO2 veneer over the northern polar cap.

“The resulting enhancement in the atmosphere of this CO2, a greenhouse gas, will begin the process of melting the water that is trapped in the northern polar cap of Mars. It has been estimated that nearly 1/7th of the ancient ocean of Mars is trapped in the frozen polar cap. Mars may once again become a more Earth-like habitable environment.

The results of these simulations will be reviewed (with) a projection of how long it may take for Mars to become an exciting new planet to study and to live on.”

Marc Kaufman is the author of two books about space: Mars Up Close: Inside the Curiosity Mission and First Contact: Scientific Breakthroughs in the Search for Life Beyond Earth. He is also an experienced journalist, having spent three decades at The Washington Post and The Philadelphia Inquirer. While the “Many Worlds” column, from which this post has been reprinted with permission, is supported and informed by NASA’s Astrobiology Program, any opinions expressed are the author’s alone.

WATCH: Here’s what drives solar wind.