I got one for you: It’s 1990, and there’s this group of 27 people who go to a six-week law enforcement leadership course in Ottawa. The first day, the newly elected class president announces that at the start of class each day, he wants someone to tell a joke. The president is from Newfoundland, and so he leads by example—basically, a Newfoundlander finds a genie in a bottle and is granted two wishes. His first wish is to be on a beach on Tahiti, which the genie grants immediately. For his second wish, he says, “I don’t want to work no more.” Instantly, he finds himself on the streets of Sydney, Nova Scotia, a town known among Canadians for its high rate of unemployment. Everybody laughs. This is a pretty funny joke.

This is also a good move by the Newfie class president. These people come from different cultures and different economic backgrounds. They have different religions, most but not all of them are cops, most but not all of them are Canadian, and most but not all of them are male. The Newfie joke does a couple things. First, it shows who he is. He’s a guy who can laugh at himself. He’s not a prick. Second, it gives all these people from all these different backgrounds at least one thing they can all laugh about. They’re all employed. The class starts to figure out who it is one joke at a time.

“The judgment of whether something is funny or not is spontaneous, automatic, almost a reflex,” writes Dutch sociologist Giselinde Kuipers. “Sense of humor thus lies very close to self-image.” Humor also takes on the shape of the teller’s surroundings: age, gender, class, and clan. Shared humor implies shared identity, shared ways of confronting reality. When we don’t get a joke, we feel left out; when we get a joke, or better yet, tell the joke that everyone roars at, we belong. “If you’re both laughing, it means you see the world in the same way,” says Peter McGraw, psychologist and co-author of The Humor Code: A Global Search for What Makes Things Funny.

Recited to a solitary outsider, they lose context, even becoming embarrassing; it is painful to tell a joke knowing that it won’t be funny.

In the gamut of humor, from the offensive to the simply dull, we find the boundaries of our own group. We’re bounded by things we don’t find funny. McGraw calls the meat in this unfunny sandwich “benign violation,” or “things that are wrong yet okay, things that make sense yet don’t make sense.” On the one side is humor that doesn’t go far enough. Consider the purported “world’s funniest joke”: Two hunters are out in the woods when one of them collapses. He doesn’t seem to be breathing and his eyes are rolled back into his head. The other guy whips out his phone and calls 911. He gasps, “My friend is dead! What can I do?” The operator says “Calm down. I can help. First, let’s make sure that he’s dead.” There is a silence, then a shot is heard. Back on the phone, the guy says, “OK, now what?”

British scientist Richard Wiseman discovered this funniest joke by soliciting jokes online, and then asking which ones were funniest. In one year, people gave almost 2 million reviews, and submitted more than 40,000 jokes of their own. You’d think in a pool that big there would be something funnier. But cognitive neuroscientist Scott Weems points out that Wiseman’s study was pinched in a couple ways. The main problem was that Wiseman rejected a lot of jokes that he deemed too dirty, sexist, or racist to distribute under his name. In the end, Weems writes in his book Ha: The Science of When We Laugh and Why, the 911 joke got the most votes because it was well shy of what he calls the “provocation threshold”—social and moral boundaries. It offends nobody, but it also doesn’t particularly impress most people. It wouldn’t have done much good in the law enforcement course.

On the other side of McGraw’s benign violation are the things that violate and fail at being harmless. At the end of the second week of class, an instructor in the course gets up and tells this joke: someone calls a lawyer’s office, and he gets the secretary. The secretary tells him that the lawyer’s dead. They hang up. A second later, this person calls again, asking for the lawyer. Again, the secretary tells him that the lawyer is dead. Then he calls again. Finally, the secretary asks the caller why he keeps calling when he already knows the lawyer’s dead. The caller says, “I just like to hear you say it!” Only two people laugh, and then there is a silent moment.

The guy’s delivery isn’t good, notes Jenepher Lennox-Terrion, a doctoral candidate in communications sitting at the back of the class. That’s the first problem. Second, the joke relies on an assumed common hatred of lawyers that may or may not exist. Third, one of the members of class, along with being a cop, is a lawyer. The real problem here is the relative standing of the lawyer-cop and the joke-teller: The lawyer-cop is well known in class, and is well liked, while the instructor is new, and is not. “Insiders, who share a common social identity, can often take liberties that others cannot,” Lennox Terrion explains. “When someone from outside puts down a high status, well-liked member, that won’t be well-received.” You have to know your audience. The instructor, in thinking himself part of the group, has misjudged his own identity.

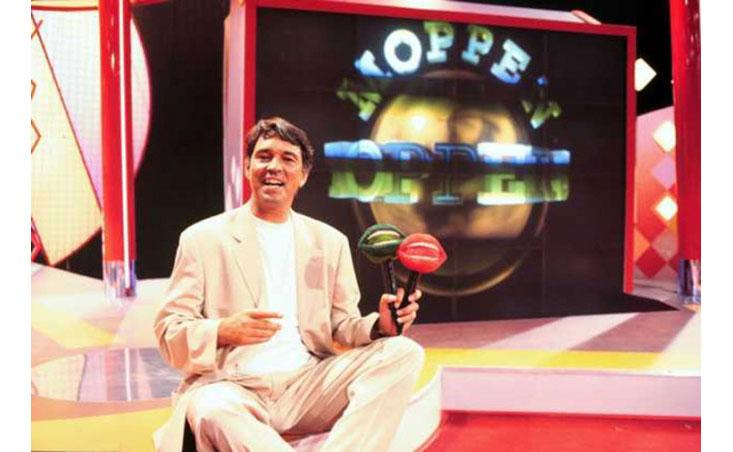

In her book Good Humor, Bad Taste: Sociology of a Joke, Kuipers investigates a specific kind of humor, of the type also favored by the Canadian cops: the short humorous anecdote leading to a punchline. This type of joke is popular in the Netherlands. There’s even a special word in Dutch for the genre—mop—and there was a popular TV show, Moppentoppers, where contestants competed to tell the best joke. It’s also a type of humor specific to a certain type of person; if you know somebody likes moppen, you could make some specific inferences about them (and their friends). Kuipers’ research supported the anecdotal evidence, which was that men like the moppen more than women, and that among these men, the less educated they were, the more they liked them. Although the Dutch tend to believe they live in a classless society, Kuipers writes that her interviews with dozens of self-identified moppentoppers made clear to her the depth of the cultural divide, as well as her place on one side of it.

“If I told the interviewees that the educated, like my university colleagues, didn’t tell many [moppen], they were quite surprised,” Kuipers writes. “They derived from this that university employees didn’t like humor or that they were boring and serious.” As one 49-year-old janitor told her, “Maybe laughing a bit more would do them good.” Her highly educated colleagues were equally bewildered by the moppentoppers. “If I run into someone at a party who’s really into jokes, then I try to escape,” a 40-year-old marketing researcher told her. “There’s no way you can have a conversation with somebody like that.”

Insiders, who share a common social identity, can often take liberties that others cannot.

Kuipers isn’t exempt from these boundaries. She struggles to talk to the moppentoppers; they, in turn, don’t want to share their jokes with her. “I had to go to great lengths to convince people that I was hard enough to hear certain jokes,” she writes. The jokes reflect an identity that Kuipers doesn’t share, both as an academic and as a woman. The moppen are usually told in a like-minded group. Recited to a solitary outsider, they lose context, even becoming embarrassing to the moppentoppers; it is painful to tell a joke knowing that it won’t be funny. “The interviews had a very specific tinge: older men telling dirty jokes to a much younger woman,” she says. “Sometimes that was awkward for both parties.”

Jokes throw the boundaries of perceived gender identities, in particular, into sharp relief. In his well-known 2007 column, “Why Women Aren’t Funny,” late Vanity Fair columnist and provocateur Christopher Hitchens asks, “Why are men, taken on average and as a whole, funnier than women?” The explanation, he posits, is basically that men are attracted to women’s bodies, and therefore, evolutionarily, women didn’t need to develop as good a sense of humor as men, who have to rely on their wit alone to get laid. In the following months, many women wrote in to point out the false assumption behind Hitchens’ argument—that his sense of humor was somehow broadly representative of both men and women in general. As Robin Schiff of Los Angeles explained in a letter to the editor, “We are funny—but only behind your backs! […]” Hitchens, she’s saying, isn’t in the club.

In other words, humor isn’t just about the joke. There’s an audience, too. The supposed un-funniness of women should be seen as a symptom of a male-centric society, writes Rebecca Krefting, which is why many publicly funny women employ what she calls “charged humor.” This humor carries a message, meant to change perceptions by knowingly pushing the boundaries of one or more dominant groups. “Despite collective desire to imagine we have achieved gender parity, charged humor and our consumption of it (or not) give us away,” Krefting writes in her book All Joking Aside: American Humor and Its Discontents. But you have to make it with the audience before you tell them off. Amy Schumer, Sarah Silverman, and Aziz Ansari all use charged humor, but also hit themes that are broad enough to catch many people in the benign-violation sweet spot. “It’s a careful dance that comics have to do,” Krefting says, “where they’ve already earned the respect of their audience, that they’re not going to lose them along the way.”

The gender role narrative as told by jokes is eminently adaptable to specific audiences. In one study, Limor Shifman, an Israeli professor of communication, followed a certain type of English-language joke in which men and women are like computers. They have names like “girlfriend 3.4” and “boyfriend 5.0,” and then they get upgraded to “husband 1.0” and “wife 1.0.” The set-up is that someone is trying to troubleshoot all the bad stuff that came with the upgrade—“the new program began unexpected child processing,” “wife 1.0 installed itself onto all other programs and now monitors all other system activity,” and “husband 1.0 uninstalled romance 9.5.” Sometimes the jokes are from the man’s point of view, sometimes from the woman’s but they basically riff on the simplest stereotypes—men like sports and don’t like feelings and women like shopping and do like feelings.

Shifman gathered as many instances of these types of jokes as she could find on the Internet. She then picked several hundred of these at random and sorted them into a list of the basic variations on the form. She translated the key bits of these jokes into the nine most popular languages on the Internet, after English: Chinese, Spanish, Japanese, French, German, Portuguese, Arabic, Korean, and Italian. Using these translations, she searched again, and came up with hundreds or thousands of URLs containing jokes of this type. As these jokes spread across the Internet and are translated, she found, they are transformed. In Japan, the jokes are overwhelmingly on the wives, while in Korea they’re largely on the husbands. In Portuguese, the jokes become more sexually explicit. In Chinese, a mother-in-law is often thrown into the mix. “People need to localize the joke,” Shifman says. “They don’t only translate it, they add those local spices to make it their own.”

When jokes can’t be un-localized, they fail. In a second study, when Shifman started with 100 popular English-language (mostly American) jokes, she found far more of them on websites with languages spoken in Europe or the Americas. She found few of them on Chinese and Arabic websites, and even fewer on Japanese and Korean websites—the greater the geographical, cultural, and linguistic distance from the United States, the more the jokes seem to defy translation. Jokes about American politics and American regional differences—jokes about a specific identity—don’t do well abroad.

Jokes that are popular globally, by contrast, hewed to broad themes, namely money and gender stereotypes; wife 1.0 goes shopping, it seems, is something everyone can laugh at. But there’s also something stale about that kind of joke. To reach the lowest common denominator, it needs to distance itself from specific identities, and loses much of its humor. Like Wisemans’ “world’s funniest,” or the kind of gag you often find in Garfield, Guinness World Record holder for the world’s most widely syndicated comic strip. There was a classic Garfield in the newspaper this weekend: Jon and Garfield are at the counter, and there’s a buzzing noise coming from Jon’s pocket. “That’s just my phone,” he says. “I have it set on ‘vibrate.’ ” But wait! “Isn’t that your phone?” says Garfield. The angle widens, and indeed, there is Jon’s phone on the counter beside Garfield. Jon’s eyes get big, and he runs screaming off-panel. “Aren’t you going to answer your bee?” Garfield says.

Ha.

It’s the beginning of the third week at officer training class and everyone’s really good buddies by now. They’re taking courses on how to talk to the media, on project management, on presentation skills and leadership techniques, as well as things like social etiquette and table manners. It’s the start of class, and a member of class gets up, and he tells a joke about a dream he had—“I was speaking to St. Peter at the Pearly Gates, and he told me that if I wanted to come in there’s some things I’d have to do. He said, ‘To pay your penance, you’re going to have to spend your life in heaven with this woman,’ and out of this cave came the worst looking hag you’ve ever seen. St. Peter pointed to her and said, ‘Latch onto her son, she’s yours.’ Then I saw [another member of the class] walking along with the most beautiful woman on his arm, so I went over to St. Peter and said, ‘Hey, what’s the score? I know [said member of class] is a lady’s man [aside to the class: ‘He is you know’], but how come he got her and I got this hag?’ And St. Peter responded, ‘Hey, she’s got to pay her penance too, you know.” The class starts laughing, really laughing, and then it breaks into applause.

This is the best reception any joke has gotten so far. It’s also the first time the person telling the pre-class joke has actually named another member of the class and made them the butt of the joke. As Kuipers writes in a collection of essays about the 2006 riots over Dutch cartoons depicting the Muslim prophet Muhammad, “Humor and laughter are directly connected with the drawing of social boundaries: laughing at someone is among the strongest markers of social exclusion in human connection.” But ridicule can actually reinforce a group when the target is confident in their in-group status. In laughing along, the target of the joke shows that he’s a good sport, thereby completing the ritual. By laughing together at each other and at themselves, the students show their membership. “Well-liked leaders tend to be most picked on,” Lennox Terrion says. “If someone considered weaker status was picked on, that wouldn’t have been funny. It didn’t really happen.”

The buddy-buddy put-downs started in the first minutes of class, even before the class president’s Newfie joke, when the course director, by way of welcoming the female officer, called the two male officers she was sitting next to ugly. All of them laughed. On the third day, someone not from Newfoundland made a Newfie joke, both reaffirming the class president’s ability to laugh at himself and legitimizing Newfoundland jokes as a consistent hit. Things developed from there. “The second week appeared to mark the beginning of more ‘uninvited’ direct putdowns,” notes Lennox-Terrion. These putdowns focus “on the backgrounds and imputed traits and motives of individuals.” The cops begin to banter, and from banter grows friendship. Bit by bit, the boundaries are pushed farther out, and as they do, a common identity forms.

In the fourth week, one of the pre-class jokes, about a blind lumberyard assistant, is dirty and seems to violate the group norm of not making fun of potentially stigmatizing attributes (which, in the context of the male-dominated class, included being female). The joke is sexist and inappropriate for the classroom, as several of the class members later tell Terrion in private interviews. But the class bursts out laughing, shouting, howling, slapping the table. The guy who told the joke knows he doesn’t have to worry. It’s four weeks in and the class members know each other well by now. The joke is a small violation, deeper into offensive territory than previous jokes, but is treated as harmless. Students request it be retold twice more over the course of the class.

The group’s sense of humor became its defining feature, says Lennox Terrion, a feature cultivated right to the end. A few days before the class members graduated, they had a fancy dinner together. They showed up looking nice, ready to put their new skills at the dining room to the test. Later that night, she says, many of them would get screaming drunk. The next morning they’d each give presentations on one aspect of what they’d learned. Soon after that, they’d all go their separate ways. There was a lot of hugging, Lennox Terrion says, a feeling of euphoria that reminds her of picking her kids from summer camp—“ ‘You’re my best friend forever!’ Even though you don’t necessarily follow up after that.” At their request, she gave a speech during the dinner, although she says she can’t remember what it was about. It was well received, but was overshadowed when, right after, somebody stood up to tell a joke.

Zach St. George is a freelance reporter based in California, writing about science and the environment. Follow him on Twitter @ZachStGeorge.