It was a profound moment of connection. Carlos Casas could feel the elephant probing him, touching him with sound. The grunts emanating from the large male were of a frequency too low to hear, but Casas felt an agitation on his skin and deep inside his chest. “I was being scanned,” he says.

At the time of the encounter, Casas was filming a project in Sri Lanka, and was holding a camera. But his interactions with the elephant gave the Catalonian filmmaker and installation artist an idea: What if instead of relying on images alone, he could use sound to create a physical connection between an audience of people and the subjects that fascinate him most, the animals with which we share life on this planet?

Sound is providing us with a lingua franca.

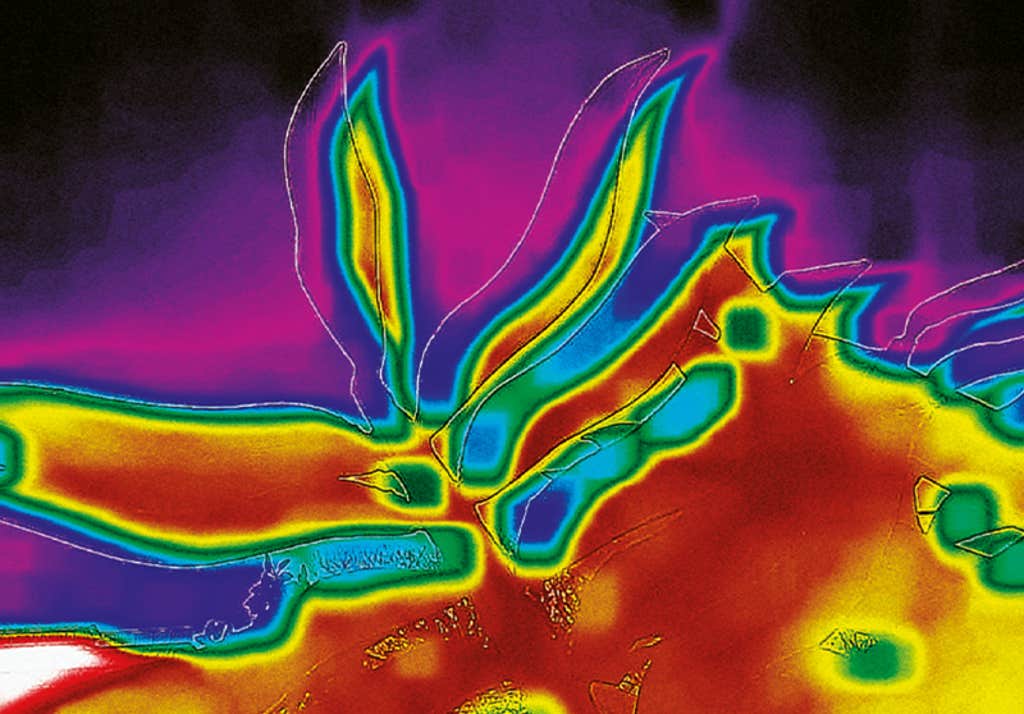

Bestiari, his audio-visual project, now on display inside a former shipping warehouse at the Venice Biennale, weaves an immersive landscape for visitors. Audio of the sounds the animals make is accompanied by video collected from remote camera traps set across national parks of Catalonia and Kenya, together with abstract film meant to capture the world as the animals see it, which is based on scientific research. A series of texts serve as field guides to each animal featured in the installation.

Entering the dark warehouse where Bestiari is housed, you are invited to lie on the floor, as if to fall asleep, before communing with seven different species: bees, donkeys, parakeets, snakes, bats, dolphins, and elephants. Each of the chosen species is represented by a speaker, customized to deliver the desired acoustics. Casas calls the speakers, “Trojan horses of meaning and communication.” The pitches and volumes were curated to be authentic to the original animal but perceptible by humans. For example, the echolocation chirps of bats have been slowed down to showcase the tonal progression of the sound. (You can explore some of the project, which was curated by Filipa Ramos, at the Instagram page for the installation.)

“I wanted to select species that are using the whole spectrum of sound,” Casas says, “and then allow these seven species to talk, to dialogue, to show their understanding of the world in a trial against the spectator.”

The idea of the “trial” comes from a medieval text: Disputa de l’ase, which translates as “The dispute of the donkey,” written in 1417 by Catalan writer Anselm Turmeda. In the story, a man enters an enchanted forest where he falls asleep and wakes up with the ability to understand the language of animals. The animals proceed to put him on trial for humans’ presumption of superiority over other beings, selecting a donkey as their spokesperson. In Bestiari, the visitor steps into the role of the protagonist and is invited to experience the world from the perspective of the animals, even when the sounds they make lie outside the range of human hearing.

Elephant rumbles can dip into infrasound, the frequencies of which fall below 20 hertz, the lower limit of the range of human hearing. But we can sense infrasound waves with our bodies. “It’s not so far from the sound that you hear when you’re a baby in the belly of your mother, or during an earthquake,” Casas says. “There is a kind of a reverberation that activates the body. It activates perception in new ways. The experience varies from person to person and can also change over time.”

Casas credits Roger Payne and Katy Payne for pioneering the use of technology to change the way we perceive the sounds different species of animals make. The researchers’ recordings of whales communicating to each other across the depths in the 1970s changed the way we think of these animals, he says. “Sound is providing us with a lingua franca,” Casas says. “In certain ways it may be our only chance to [usher] a new understanding of other species.” Casas is not interested in translation, however, but in a shared embodied experience, a “sensorial transformation.”

In the medieval text, the animals lose the trial. The human argues he was created in the image of God, therefore making him superior. “But it is what we call a Pyrrhic victory,” Casas says. “It would have protected the author from the Inquisition, against the blasphemy of accepting that we are all the same.” In Bestiari visitors are left to reach their own conclusions. “It was important to give that ending back to the spectator,” Casas says, “and decide who we are. Are we all together and equal in this dialogue between species?” ![]()

Lead image: Vladimir Turkenich / Shutterstock