Back in the day, before the speed of light was considered the slow lane, “extreme” sports—bungee jumping from bridges, hang gliding over volcanoes—were barely deadly and almost quaint. But with the advent of hyperflight, adventure sports are undergoing a revolution. Thrill seekers are now testing boundaries far beyond Earth’s atmosphere: scaling mountains on Mars, surfing powerful stellar gas jets, and playing chicken with black holes.

Profiting handsomely from all this action is Jimmy Doogle, founder of the Extraterrestial Sports and Programming Network (ETSPN). “Thank God for the spacetime continuum,” he says with a laugh, during which he earned another trillion dollars. Nautilus recently caught up with Doogle to find out what today’s adrenaline junkies do for a fix.

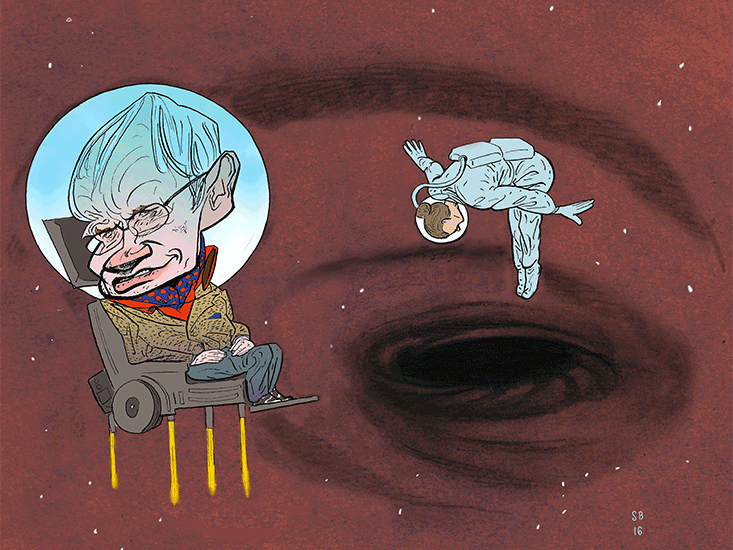

Black-Hole Diving

According to Einstein’s theory of relativity, nothing escapes a black hole. So a diver’s goal is to get as close as possible to the point just before the point of no return. It’s a calculated risk. It’s not yet clear, for instance, how this invisible boundary, which may be in constant flux, should be marked. So there’s no way to know you’ve crossed it until it’s too late.

To date, 27 daredevils have taken the leap. But because no one has yet returned, no record has been established. Nevertheless, there’s plenty of optimism back at the Bungee Hole Space Center near black hole A0620-00, in the constellation Monoceros, where support teams are camped out. On the wall over the bar, where robotic arms serve cocktail capsules, 27 stopwatches tick away. The longest-running clock, timing presumed leader Buck “Rogers” Ruttle, reads 61 Earth years.

However, diehard fans remain hopeful. Even if black holes swallow every last diver, they point out, a centuries-old assertion by immortality pioneer Stephen Hawking, if true, may assure their heroes still receive their due fame. According to Hawking’s calculations, black holes “leak” matter in the form of radiation and particles, and eventually explode, spewing everything they consumed. That’s why divers can always find sponsors. Even a smidgen of DNA rocketing back into ordinary spacetime would trigger thousands of branding deals.

Flaming Ice Hockey

Modern athletes pride themselves in their ability to withstand boiling temperatures and frozen terrain. But it wasn’t until explorers mapped the planet Gliese 436b that competitors got the chance to tackle both extremes at once. Roughly the size of Neptune, Gliese orbits far closer to its sun than Mercury does to ours, making its surface a balmy 820 degrees Fahrenheit. At that temperature, you’d think the planet would be all gas. In fact, immense pressure in Gliese’s interior compresses water into an exotic phase of ice known as Ice X, in much the way pressure in Earth’s interior turns carbon into diamond.

The result is a world cloaked in “hot ice” and bathed in steam. A decade ago, 10 tenacious hockey teams flew the 30 light-years to Gliese for the first of what has become an annual tournament. The flaming puck makes the action easy to follow. Traditionalists grumble that players hop instead of glide, but there’s not much to be done about that: Unlike ice on Earth, Ice X isn’t slippery. The molecules at its surface are under such great pressure that friction from a skate won’t soften the top layer of ice enough to allow the skate to slide smoothly across it.

Recently, Gliese’s hard-core conditions have begun attracting other athletes looking for an edge. Nordic explorers, deeply discouraged by the last piece of ice melting at the North Pole, are some of the newest arrivals. And when you tune into a hot ice hockey game on ETSPN, Doogle says, keep an eye on the arena between periods: You might just catch a figure skater emerging from the mist, skintight asbestos costume aflame.

Nebula Gas Surfing

The coolest natural spot known is the Boomerang Nebula, where the temperature is just 1 degree above absolute zero (–459 degrees Fahrenheit). The nebula was born when a star in the constellation Centaurus began dying, a process that causes it to expel gas from its core. The gas gushes so fast—10 times faster than in a typical nebula—that it expands. And as it expands, it gets extremely cold, much like when air spews out of a tire nozzle. Even empty space, bathed in radiation from the Big Bang, is warmer.

But Boomerang’s gelid climate doesn’t seem to bother the wind surfers who travel 5,000 light-years to ride its “rad” 100-mile-per-second gas stream. “Any paddlepuss can surf on bonded hydrogen and oxygen,” one veteran scoffs. The only downside of this “chill ride,” she says, is when the gnarly nebular winds peter out and you find yourself 100,000 miles away from the launch site, disoriented and alone, floating aimlessly in the darkness until you can get enough bars on your hologram phone to call an Uber.

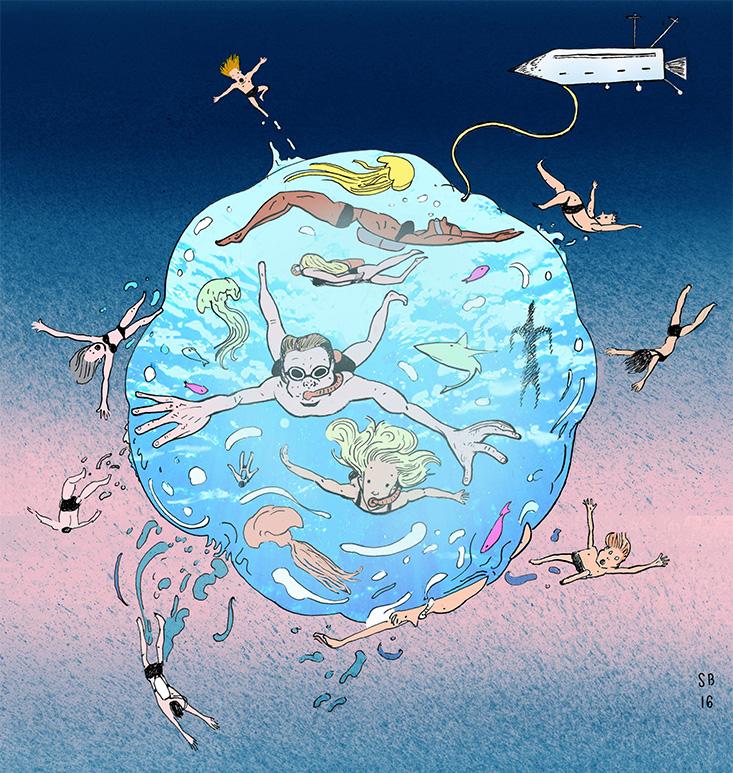

Zero-G Swimming

In a 1994 paper in Proceedings of Space, Japanese scientists rightly predicted that a major obstacle to space pools would be rocketing hundreds of tons of water into the void. After countless hauls, and several rounds of fundraising, the space hotel industry finally opened the first Zero-G water park—only to be sued by the survivors of the first eager swimmers: Without gravity, there was no obvious way to find the “surface” of the 85,000-gallon floating blob. But engineers quickly found a fix. By spinning the blob, they could induce just enough gravity to create “up” and “down.”

Guests were happy enough. But the development made endurance swimmers, who were running out of new Earthbound challenges, drool. Much to their embarrassment, however, the pioneer of intergalactic water sports turned out to be a stoned teenager named Greco Roman, who, while vacationing with his family at a space casino, broke into its pool to swim in the endlessly rotating lap lane. Still at it two days later, he inadvertently set the first Guinness World Record for space swimming. Professional swimmers flocked to space pools to beat it. It wasn’t long before they were clandestinely importing sharks and jellyfish “to make things more interesting.”

The Draco 1000

After ticket sales among billennials, the first generation to grow up with intergalactic travel, plummeted at the annual Baja 1000 off-road race in Baja California, Mexico organizers announced a new location: the planet TrES-2b. About 750 light-years east of Mexico in the Draco constellation, the gas giant is billed as “the darkest place in the universe.” Reflecting only 1 percent of the light that strikes its surface, it is, in fact, blacker than coal.

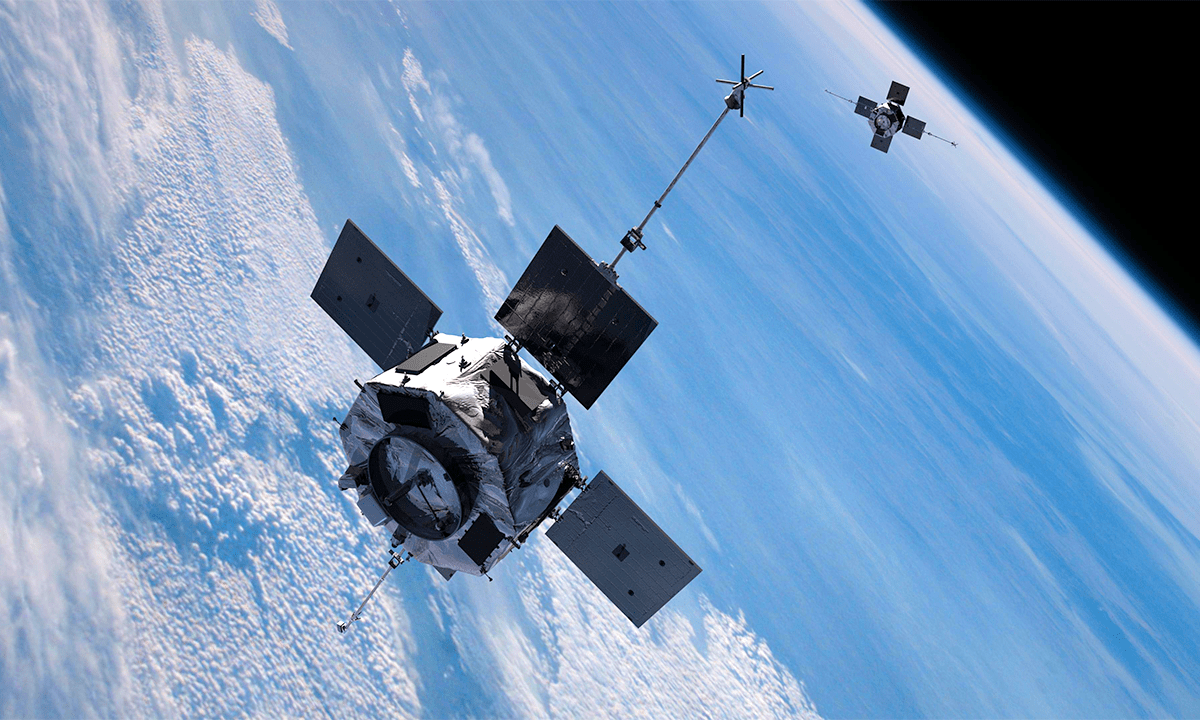

Like hamsters in plastic balls, Draco 1000 racers propel insulated space orbs, many of them made by welding together decommissioned NASA parts. To navigate the course, pilots rely on instrument panels, Google Galaxy, and whatever they can make out in the red glow of the planet’s 1,800-degree surface. Like barefoot devotees walking over glowing embers, they are advised to keep moving.

Due to TrES-2b’s low reflectivity, the race is impossible to broadcast from overhead, Doogle says. But ETSPN has created a hit show with dash cams, satellite trackers, and open communication channels between the grizzled contestants, most of whom have been banned from driving elsewhere. The seat-of-the-pants navigation adds to the drama. In one infamous incident, a pilot bought what he thought was a rare terrain map on eBay Mars only to discover mid race that he was looking at downtown Pittsburgh.

The Next Seven Summits

It used to be a big deal, back when your great-great-great-grandparents’ heads were still attached to their original bodies, to scale the highest peak on each of Earth’s seven continents. But after the feat had been accomplished more than 1,000 times, including by an infant who learned to walk on the way down, dopamine-addicted climbers turned to the “next seven,” a circuit of some of the highest and most treacherous peaks in the Solar System.

The protective suits needed to bag peaks 8 through 14 may be cumbersome. But what you lose in mobility, you gain in lightness. After summiting Mons Huygens on Earth’s moon, which most climbers dismiss as a training run (and which is currently closed to clear the litter), mountaineers head to Mars for Olympus Mons, whose peak towers nearly 17 miles above its base. (By comparison, Everest’s base-to-peak length is about 2.3 miles.) Other mountains on the tour include Venus’s 4-mile-high Skadi Mons, whose slopes are covered in lead sulfide “snow”; Rheasilvia, which rises 14 miles from the center of an impact crater on the asteroid Vesta; and Norgay Montes, an ice peak looming 2 miles over the surface of Pluto.

Chip Rowe is a writer based in New York who rode a skateboard once in the fourth grade.