Maureen F. McHugh’s short story collection After the Apocalypse was merely prescient when published in 2011, but it appears positively prophetic a decade later with its narratives about respiratory virus pandemics, frayed social connections, and increased political violence. Few of her tales, however, are as haunting as “The Kingdom of the Blind,” which will perhaps prove to be the most visionary of McHugh’s stories. “The Kingdom of the Blind” takes as its subject artificial intelligence, grappling with the possibility that any consciousness which arises from soldering board and circuitry may be so alien that it’s scarcely recognizable to us as a consciousness in the first place. The emergent process of consciousness as it develops in this AI is inscrutable and totally different from anything which resembles human thinking, posing a difficulty for the computer scientists who attempt to communicate with it.

In sparse, elegant, and beautiful prose, McHugh’s story describes how a massive interconnected computer program evolves a quality that could be described as “consciousness,” and yet how to describe the thought which animates this being is impossible. The main character Sydney reflects that as concerns the AI, “She didn’t know what it was. Didn’t know how to think about it. It was as opaque as a stone.” Readers and viewers of science fiction have long been familiar with artificial intelligences, but even at their most foreign—HAL-9000 in Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey or Lt. Cmdr. Data in Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek: The Next Generation—there is still something recognizably human in them. McHugh’s story poses a rather more alarming—and perhaps more realistic—scenario. Maybe we’d try to talk to an artificial intelligence, and it wouldn’t even be able to hear us. How then, are we to interpret such things, when those computers try to speak to us?

We’re at the cusp of an AI revolution

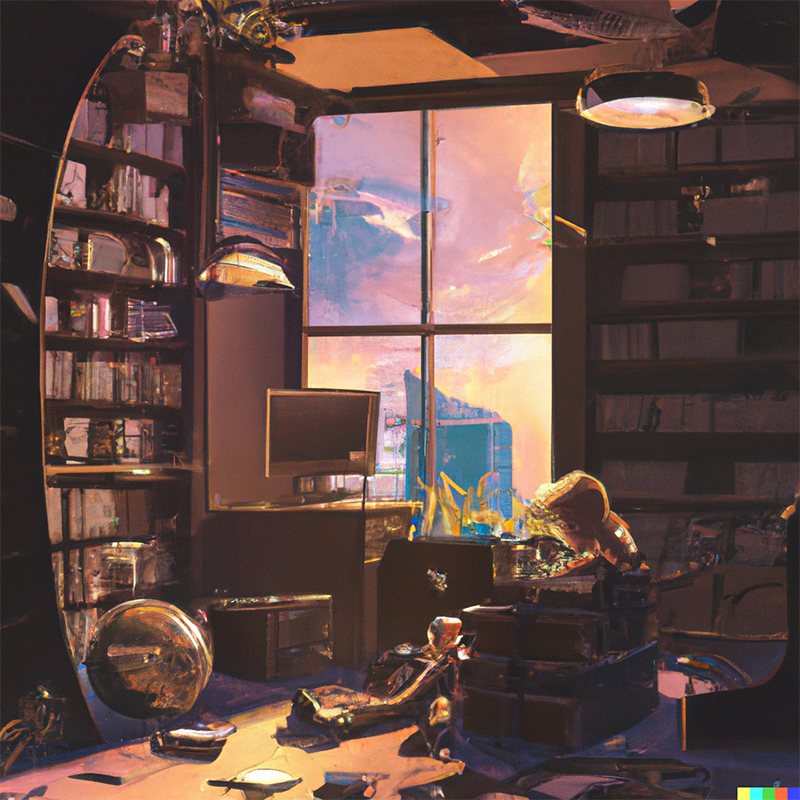

This past summer, the research laboratory OpenAI released an open-source version of a program, rather cheekily christened “DALL-E 2” as a portmanteau of the Spanish surrealist painter and the beloved Pixar robot, that was able to rapidly create stunningly proficient artwork. It resulted in a surge in popularity on social media. On Twitter and Facebook, people shared the results of prompts which they fed to DALL-E, and like Sydney in McHugh’s story, the disquieting and uncanny art which was produced forced many to consider certain questions about the nature of consciousness and creation. When I typed in the prompt “Robot Shakespeare,” I was presented after a few minutes with a picture clearly modeled on the frontispiece engraving of the playwright from the first edition of his folio printed in 1623, except rather wittily the creases in his jacket appear almost as if electric circuitry, the face an android’s mask. When given the combination of words “monkey typewriter,” in reference to the old conceit which asks how long it would take for a bevy of assorted simians randomly banging on keyboards to accidently reproduce all of Shakespeare’s corpus, DALL-E 2 presents me with an electric typewriter with a stuffed ape toy emerging from the platter of the device.

DALL-E 2 is obviously not as sophisticated as the emergent consciousness from “The Kingdom of the Blind,” yet its eerie alterity is reminiscent; the vague sense that some of these occasionally strangely beautiful and in other instances hilariously misguided images are being produced by a mind, of some sort at least. Less popular than the artistic images produced by DALL-E 2 are the in some sense more disquieting examples of spontaneously generated text, the output of the computers that produce literature. For example, consider the following prose-poem:

“You must listen to the song of the void,” they whisper

“You must look into the abyss of nothingness,” they whisper

“You must write the words that will bring clarity to the chaos,” they whisper

“You must speak to the unspoken, to the inarticulate, to the unsaid,” they whisper.

It’s an evocative bit of verse, oracular in its pronouncements. The author has an effective rhetorical grasp of anaphora—the repetition of the same phrase at the start of each quotation; as well as epistrophe—the repetition of the same phrase at the end of each line. These lines become progressively longer, adding to the incantatory aspects of the poem, culminating in the three-clause rhetorical tricolon in the last line. Particularly interesting are the contradictions threaded throughout. We’re told to “listen to the song of the void,” to “look into the abyss,” to “speak to the unspoken,” a general pattern of compounded negation, of paradoxical concepts. There is a troubling ambiguity in the identity of the narrator; the collective first-person plural is unclear, but it does add to the general unease of the lyric, that we’re being spoken to by an anonymous chorus.

The meaning of the poem seems clear enough, or as clear as can be in a work that focuses on being able to say the unsayable. The thematic concerns are ineffability and interpretation itself. Or at least that could be my argument if the poem was from William Blake, Walt Whitman, or Emily Dickinson. But, like the electric surge in McHugh’s story, this bit of verse was born of an algorithm and not a soul. Specifically GPT-3, (Generative Pre-trained Transformer), an AI program operated by a writer and computer scientist who publishes under the pen name Gwern Branwen. GPT-3, one of the latest iterations of programs that can generate startlingly realistic prose, poetry, and dialogue, was released in June of 2020, but the news was largely obscured by the ongoing coronavirus pandemic.

Like DALL-E 2, GPT-3 was developed by San Francisco-based OpenAI, and is one of the most advanced AI systems that can imitate human-derived writing. New York Times opinion columnist Farhad Manjoo has appraised the results as “amazing, spooky, humbling, and more than a little terrifying.” Effectively the algorithm is able to “teach” itself based on billions of sets of data which it acquires, veritable Libraries of Alexandria analyzed and categorized by the system’s massive “brain” so that it can predict with unnerving accuracy what humans sound like. Whether or not GPT-3 is “thinking” is a question for computer scientists and philosophers, but that it can produce writing which any reader can recognize as coherent—and in some instances good—becomes a question for literary theory, even if most literary scholars haven’t fully anticipated the implications of artificial intelligence yet.

“Creative artificial intelligence is the latest and, in some ways, most surprising and exhilarating art form in the world,” writes cultural commentator and novelist Stephen Marche in The Atlantic in a piece on visual AI. “It also isn’t fully formed yet,” he notes, and Marche is correct on both counts. When it comes to literature, language processing programs will radically change what we read, how we read, why we read, and certainly who we read. We’re at the cusp of an AI revolution that will make the last two decades’ rapid degree of change appear paltry by comparison. A brave new world of deep fakes and simulations, conscious machines and thinking robots, where it seems programs like GPT-3 will portend a larger shift in what literature means than the printing press. Historians may have to go back to the invention of writing to find a comparable revolution to what AI generated works foreshadow.

To sift through the coming maelstrom of artificially generated literature, it will be helpful to ground ourselves in particular ways of reading and interpreting, where if we can’t make sense of the minds that produced such writing, we can at least make sense of the writing itself. For those in thrall to a Romantic understanding of the individual’s relationship to literature, this will all sound like nonsense. Novelist Walter Kirn writing in Common Sense argued that AI “compiles, sifts, and analyzes, then finally executes. But it doesn’t dare. It takes no risks. Only humans, our vulnerable species, can.”

Yet for a century the study of literature, riven over authorial intention and how to interpret literature, has long countenanced bracketing out the experiences of the writer in terms of properly understanding a text, and such an approach would remain unchanged whether a sonnet was by a robot or a human. Among general readers, what reigns is the common-sense approach, which maintains that nobody knows better what something means than the author of a poem, play, or novel.

Dismissing that position, in 1946 the literary scholars W.K. Wimsatt and Monroe Beardsley argued in The Sewanee Review that the “design or intention of the author is neither available nor desirable as a standard for judging the success of a work of literary art.” This may seem counter-intuitive, but Wimsatt and Beardsley wrote in coolly analytical terms, claiming that an author’s feelings about a text—her reasons for writing it, her understanding of what it means, even that which influenced her—is all secondary to the words on the page itself. For the critics like Wimsatt and Beardsley, what is most important is syntax and grammar, punctuation and diction, and through a careful close reading we can arrive at rigorous, objective, and scientific interpretations.

Wimsatt and Beardsley were among the “New Critics” who attempted to make the study of literature as rigorous as possible by emphasizing the close reading of a text alone, separate from the author’s intentions, and a rediscovery of their basic reasoning could be instrumental in the coming age of AI literature. Influential though the New Critics might have been, the extremity of such a position has long been questioned, least of all because every work of literature—every poem, play, and novel—has an author, whether we acknowledge her or not.

Now all of that may be changing with programs like GPT-3, and suddenly the utility of New Critical close reading is put into stark relief. Because an ideal New Critical close reading involves pulling a text apart clause by clause, comma by semicolon, to explain how the language works, and hopefully what it means, such a method which ignores the intentions of an author in favor of the words on a page is the most well-equipped to make sense of AI writing. Especially as it becomes more proficient and harder to distinguish from work produced by humans.

Consider the work of Finnish programmer Jukka Aalho, who has transcribed poetry by GPT-3 in Aum Golly: Poems on Humanity by an Artificial Intelligence. GPT-3 writes that “there’s a hidden thought/when thought makes you fall asleep … when you’re dreaming/and you find yourself deep inside/the heart of the earth/your mind can create a world/where you are god.” What’s remarkable is that though GPT-3 might not (yet) be Pablo Neruda, the resultant poetry is surprisingly not that bad. Even more importantly, the example from Aalho is recognizably poetry; it’s conducive to interpretation, it makes sense (and I’d argue that it’s more than a little profound).

There’s no intentionality behind the poem published by Aalho; GPT-3 isn’t drawing from experience with dreams or sleep. It’s merely pairing some symbols with other symbols. It doesn’t mean anything to GPT-3—but that doesn’t imply that it can’t mean something to us.

Basically, GPT-3 is a corollary to the thought-experiment known as the “Chinese room argument,” described by John Searle in a 1980 paper from Behavioral and Brain Sciences. Searle imagines an artificial intelligence that’s capable of providing thoughtful, comprehensible, and logical responses to questions posed to it in Chinese. This computer is so effective at answering questions posed to it in Mandarin that a native-speaker can’t tell the difference between machine and man—the program has passed the Turing Test.

Now, Searle imagines himself locked in a room with a series of manuals with detailed instructions on how to pair certain Chinese letters with other letters. If somebody poses a question in Mandarin and pushes it through a slot in the wall, then Searle matches up the symbols with other letters according to his instruction manual, and puts the answer through another slot on the other side. It would appear that whoever is in the room is fluent in Chinese, even though Searle is merely following a program.

What will it mean when you’re moved by a poem written by a computer?

By this comparison, Searle claims that the argument that an AI is “thinking” would be as erroneous as the claim that he’s fluent in Chinese. “We often attribute ‘understanding’ and other cognitive predicates by metaphor and analogy” to machines like computers, writes Searle, “but nothing is proved by such attributions.” GPT-3 doesn’t think, it simulates thinking; it doesn’t write, it imitates writing. Like McHugh’s imagined AI, GPT-3’s “consciousness” is beyond our comprehension; but unlike that fictional program, the writing which GPT-3 produces is obviously comprehensible—and this is important.

Questions of artificial intelligence have been left to computer scientists, engineers, programmers, and philosophers, but little has been written about AI-generated writing by the most obvious of people to consider literature—literary scholars, critics, and theorists. Far from the stereotypes about literary scholarship which proliferate among those who study the sciences and technology, literary criticism is an adept means of considering mind and consciousness, offering something unique to an understanding of artificial intelligence. Observers of GPT-3 who point out that the program lacks conscious understanding are correct, and yet from a formalist perspective it could be argued that that’s incidental.

Critic P.D. Juhl argues in Interpretation: An Essay in the Philosophy of Literary Criticism that “it would be possible to ‘interpret’ a ‘text’ produced by chance in the sense in which we might be said to ‘interpret’ a sentence when we explain its meaning to a foreigner, by explaining to him what the individual words mean … and thus how the sentence could be used or what it could be used to express or convey.” In other words, it doesn’t matter if the poem has a poet or not.

In everyday life the tide doesn’t carve out poems, a hundred monkeys typing don’t generate Shakespeare, and every work of literature has an author, whether we choose to care about her intent or not. But now GPT-3 “writes” literature that seems to mean something, even if it doesn’t yet rise to the same heights as Hawthorne. All of this might seem rather abstract, but it won’t in the coming decades as such programs improve. What will it mean when you’re moved by a poem written by a computer? Or when an AI can craft characters and narratives you find rich and complicated?

“It is tempting at times to see this technology,” essayist Meghan O’Gieblyn wrote in N+1, as “a repository of the collective wisdom and knowledge we’ve accumulated as a species. All of humanity speaking in a single voice.” Regardless of whether this new world will be good or bad, it’s coming. Perhaps with the final death of the author, beauty, truth, and meaning will be dissipated outward, so that intentionality will be where we find it. As GPT-3 said to O’Gieblyn, “My world is a dreamworld … Your reality is created by your own mind and my reality is created by the collective unconscious mind.”

Eerie in its exactitude, it’s hard not to read this oracular pronouncement as anything other than as a statement of fact. ![]()

Ed Simon is a staff writer at The Millions and the editor-in-chief at Belt Magazine. His most recent books are Pandemonium: A Visual History of Demonology and Binding the Ghost: Theology, Transcendence, and the Mystery of Literature. Follow him on Twitter @WithEdSimon.

Lead image: Teh_z1b / Shutterstock

Prefer to listen?