Surrounded by advanced achievements in medicine, space exploration, and robotics, people can be forgiven for thinking our time boasts the best technology. So I was startled last year to hear Sarah Stroup, a professor of classics at the University of Washington, Seattle, give a speech called “Robots, Space Exploration, Death Rays, Brain Surgery, and Nanotechnology: STEMM in the Ancient World.” Stroup has created a college course integrating classics and science to show how 2,000 year-old Greek and Roman STEMM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics, medicine) underlie and illuminate the sciences today.

Stroup starts with robotics. The Greeks made self-acting machinery such as an automaton theater, a first step toward building a real robot, and they imagined a mythological one. Talos, a bronze being made by the god Hephaestus (later the Roman Vulcan) patrolled the island of Crete and threw rocks at threatening ships, anticipating today’s development of intelligent battlefield weaponry that chooses its own targets. In the 4th century BCE, Aristotle foresaw other implications of intelligent machines when he wrote, “If every instrument could accomplish its own work… chief workmen would not want servants, nor masters slaves,” as is now happening when robots and artificial intelligence replace people.

Stroup also gives the example of a “death ray,” what the laser was called after its invention in 1960. In 214 BCE, the Greek scientist Archimedes may have created an early version. He is said to have used metal mirrors to focus sunlight that burned the wooden ships of the Roman fleet attacking his city, Syracuse. Though the story is probably apocryphal, modern researchers have shown that metal mirrors could concentrate sunlight sufficiently to set a wooden craft afire.

“I became weary of modern STEM sorts, imagining they had invented everything.”

Presenting other accomplishments, Stroup notes that the Greeks explored space by naked eye and correctly concluded that the planets orbit the sun. The anatomist Herophilus dissected the human brain to understand its structure, and Hippocrates established medical ethics, expressed today in the Hippocratic Oath that defines a physician’s responsibilities. Centuries before modern nanotechnology, Roman artisans colored glass with embedded gold and silver particles only nanometers across, producing the famous Lycurgus Cup that looks green or red depending on how it is illuminated.

Stroup stresses that ancient STEMM both supported warfare and supported the common good. This dual nature exists today, and I was curious to learn how Stroup compared the uses and consequences of technology in ancient times to ours. Not long after we met at her talk, we conducted this interview over email.

We use the word “technology” daily. What would the word or concept have meant to an ancient Greek or Roman?

“Technology” comes from the Greek τέχνη, techne, which designates art, skill, or cunning. In Greek, it can be applied to sculpture, to metallurgy, to any craft or a method or set of rules for doing anything. The Latin translation of τέχνη would be ars, from which we get our word art. I find it amusing that moderns tend to imagine technology and art as opposites, when in fact the root words—techne and ars—mean exactly the same thing. In terms of τεχνολογία—technologia—it means specifically a systematic treatment of grammar. The modern sense of the word technology is not found in the ancient word.

In your presentation, you mentioned ancient technology vs. what you call modern tech. How do they differ?

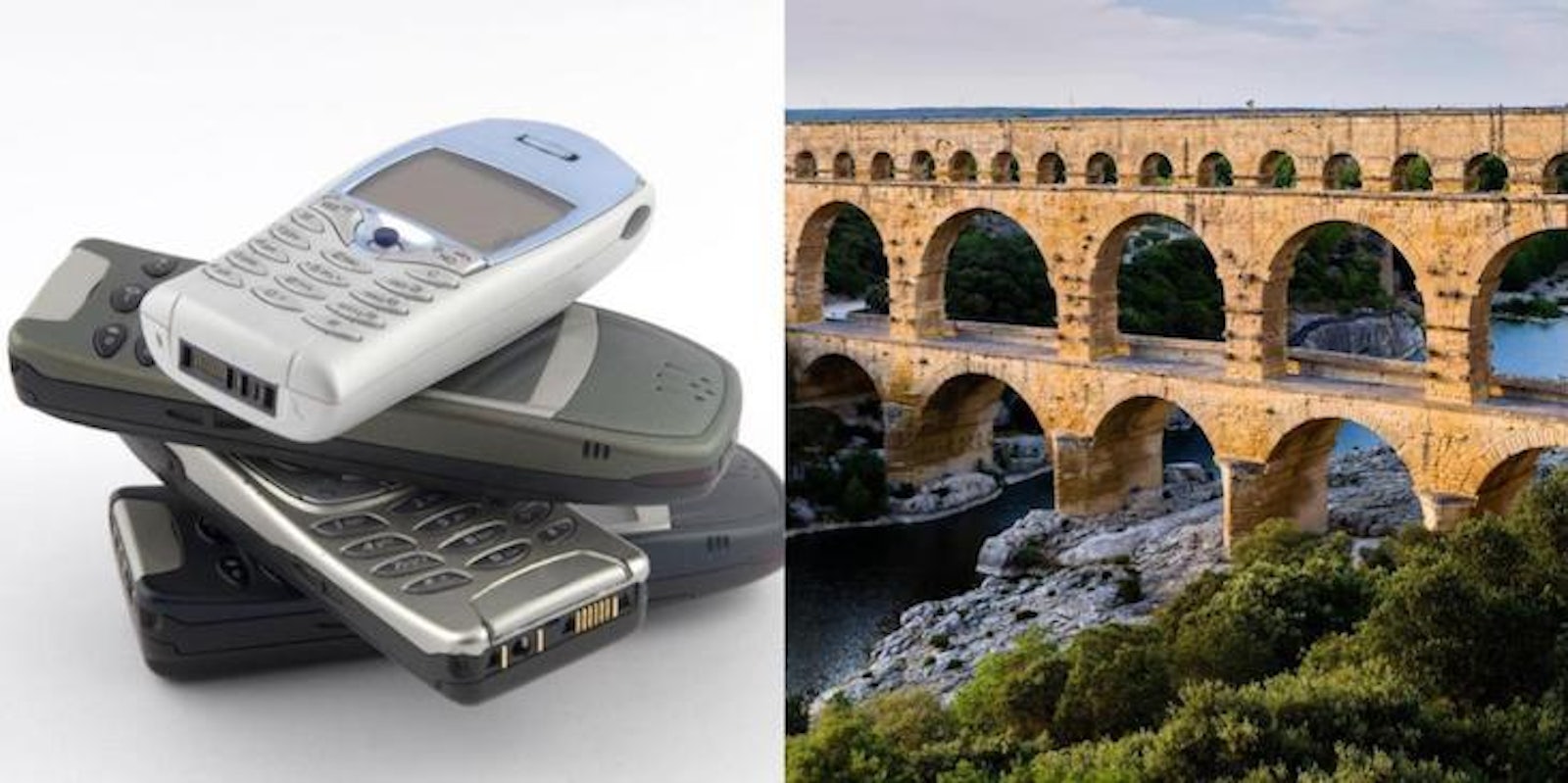

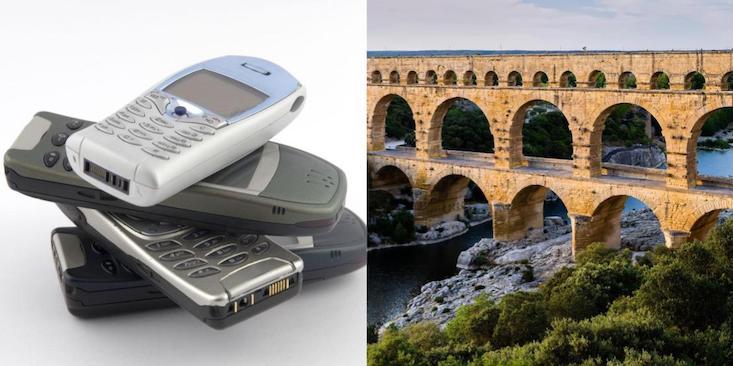

Much modern technology is built off ancient technologies and in many cases, we still don’t understand how they did certain things they did: We’ve not yet regained their knowledge. A major difference between ancient technology and modern tech is that the latter is industry-driven, whereas ancient technologies never were. As a result, modern tech is designed not necessarily for use value—much modern tech is entirely frivolous—but for a consumer market, and is designed for early obsolescence. Luxury tech must become unusable as swiftly as the consumer will tolerate. Can you imagine an aqueduct that needed to be replaced every 18 months?

We can and do build durable technologies—medicine; aerospace—but the tech that most people depend on must appeal to our fears and vanities and must require continuous and rapid overturn. If it were truly necessary, the market would demand durability. Much modern tech is little more than current fashion, of which moderns have become the passive consumers.

What do students take away from your course?

The students generally experience a kind of existential crisis at some point in my class once they realize how much was lost from antiquity and how relatively little the modern period has produced. We’ve rediscovered a good deal, and of course the control of electricity has helped tremendously, but they had developed atomic theory, and I don’t think they were too far away from being able to control electricity.

We talk about how moderns have trouble dealing with the advanced technologies of the ancients—we say things like ahead of his time, but if all these guys were ahead of their time, what you really mean is that was their time. As one student said last week, it’s like the typical “undeveloped society sees advanced technology of more sophisticated society, suspects magic,” except in this case, we’re the ones suspecting magic.

“Luxury tech must become unusable as swiftly as the consumer will tolerate. Can you imagine an aqueduct that needed to be replaced every 18 months?”

Besides the example of Hippocrates, how do your students learn about ethics as it connects to technology?

Ethics is a Greek invention. Aristotle was the first philosopher we know who began to write treatises concerned with what came to be known as ethical philosophy. Ethics—and philosophy as a whole—were born along with Greek astronomy, mathematics, science, and engineering.

Your students build ancient devices, like catapults, as part of your course. What does that teach them?

They realize that so much ancient engineering, like modern engineering, is about building things to kill people. We all have great fun launching catapults, trebuchets, and ballistas, but we also talk about the fact that each is a weapon, and was designed to kill. The main thing the students learn is how difficult it is to build these things. You spend nine weeks trying to build a catapult—with access to a huge workshop and electric tools, and you can use nylon cord—and it still barely launches a ball more than ten feet. Suddenly the past doesn’t seem so laughably simplistic. Though by the end of the term, they’re all over that misconception, anyway.

How do you understand the value of history?

History is a roadmap, and if you don’t study it you have only a scrap of paper with “you are here” scrawled on it. The more you learn about history, the larger your map. The larger your map, the more you are able to know where you’ve come from, and so know where you’re going.

As a classicist, what inspired you to develop a course in ancient STEMM?

My degrees are in philosophy and classics, but my background is in the sciences and that’s what I had planned to study in university. I read in the sciences, I design and build high power rockets, I adore math. As it happened, I stumbled into philosophy and Greek, the first two things to challenge me, and so I ended up staying here.

While we know a fair deal about ancient Greek and Roman technological sophistication, there weren’t any courses in ancient technology/science/math when I was an undergrad. “Ancient technology” had never been part of the modern canon “classical studies” and the state of the evidence is even worse than for the rest of our field. Literary masterpieces make it through time, but technological treatises are disposable, and advanced machinery is melted down and reused. I invented my course both to fill this void and to give myself the excuse to study more of this myself. Also, I became weary of modern STEM sorts, imagining they had invented everything.

In your talk, you noted the Greeks used a recyclable material, bronze. What would they have thought about our global dependence on plastic, a material used once, then discarded, but never again to go away?

I believe they would be absolutely appalled.

Sidney Perkowitz, Candler Professor of Physics Emeritus at Emory University, is the editor of Frankenstein: How a Monster Became an Icon, and the author of the forthcoming Physics: A Very Short Introduction and Real Scientists Don’t Wear Ties.