If you treasure the recipe for your aunt’s special pasta salad, you might have something in common with Neanderthals. Our ancient ancestors may have passed down family cooking traditions, according to recently reported findings from two caves in Israel.

Between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago, two groups of Neanderthals spent their winters in caves around 40 miles apart at sites called Kebara and Amud. While the two communities used comparable flint tools and had access to similar prey, such as deer and gazelles, scientists have recovered evidence that the human ancestors seem to have prepared their food in unique ways. This suggests the influence of distinct cultural practices potentially passed down among generations of Neanderthals, the team of archeologists reported in the journal Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology.

At the Kebara and Amud caves, researchers closely inspected Neanderthal meal leftovers from throughout their millennia-long stay, and noticed some key differences. For one, the Kebara Neanderthals seemed to prefer hunting large animals more than those at Amud, cooking more aurochs—an extinct type of bovine—along with animals in the horse family.

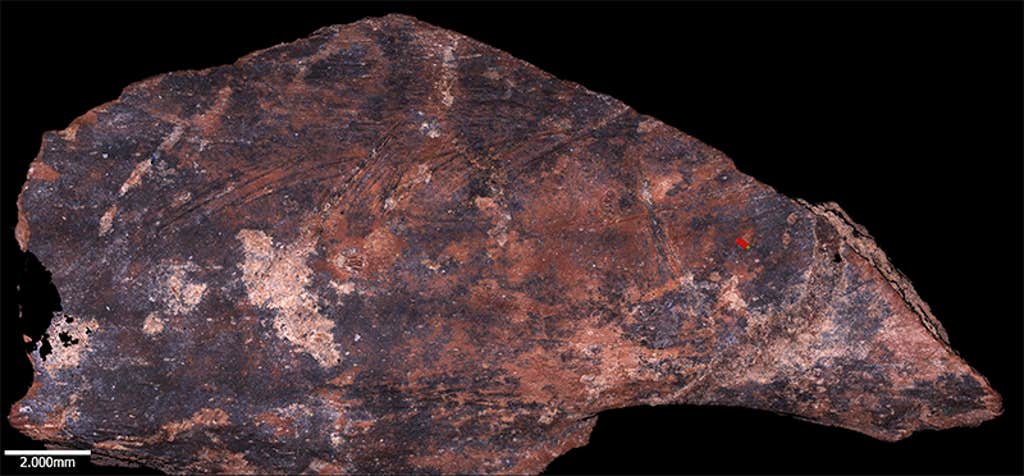

There were also differences in cut marks on the bones of hunted and cooked animals. At Amud, the cut marks tended to be more clustered and curved compared with those observed at Kebara. This could stem from butchering preferences: The Neanderthals at the Amud cave perhaps tended to bring carcasses home, rather than cutting them up on-site after a hunt. They might have left the meat out to dry, like today’s butchers often do to enhance tenderness and flavor. Carving decaying carcasses could result in “haphazard, deep, and sinuous cut-marks,” the authors write.

These cut marks could also be affected by the number of people involved in butchering, and the specific cutting techniques employed. But more research is needed to grasp the specifics of these ancient hominins’ culinary practices—and maybe even unearth some Neanderthal family recipes. ![]()

Lead image: Lucky clover / Shutterstock