In 2002, when the Oakland A’s replaced their MVP first baseman Jason Giambi with 32-year-old Scott Hatteberg, a washed-up catcher with a bum arm, longtime baseball scouts figured the unpredictable A’s had finally gone completely around the bend. As journalist Michael Lewis recounted in his book, Moneyball, even “Hatteberg hadn’t the slightest idea why the Oakland A’s were so interested in him.”

As everybody who read Lewis’ celebrated 2003 book knows, the A’s signed Hatteberg with the encouragement of the team’s bright young assistant general manager, Paul DePodesta. Schooled in economics at Harvard, DePodesta was developing a new way to interpret player statistics, finding value where nobody else was looking. With players like Hatteberg, the A’s, led by general manager Billy Beane, took an operating budget that was a fraction of that of the Yankees or Red Sox, and assembled teams that didn’t cost a fortune but won games like baseball royalty.

As we were planning this chapter of Nautilus, about new ways to interpret unlikely events and situations, we knew we had to talk to DePodesta, who was with the A’s from 1999 to 2003. (Also, we are baseball fans.) He gladly agreed to an interview.

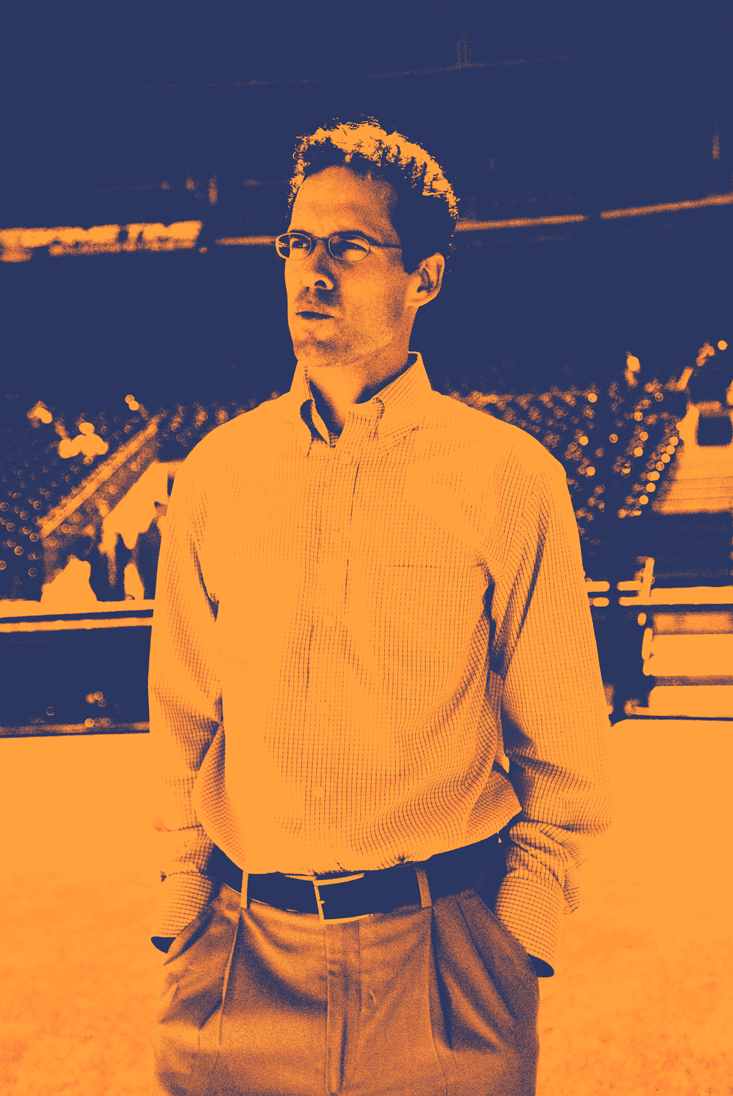

Today DePodesta, 40, is vice president of scouting and player development for the New York Mets. He joined the Mets in 2010. Since the publication of Moneyball, his star has dimmed, notably after he was fired after two years as general manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers, where some of his trades were razzed like a bad movie. Moneyball, the Hollywood version, where he was portrayed by Jonah Hill, put him back in the spotlight. However, DePodesta didn’t want his name used in the movie. Although he liked the book and screenplay, he felt both amounted to a caricature of him. “I just didn’t feel comfortable that however I was going to be portrayed in the movie was going to be how 99.9 percent of the public imagined me to be, and would assume that whatever was in the movie was absolutely true, which it wasn’t,” he said. “The other problem was I wasn’t all that interested in the attention. It had already happened from the book. And I didn’t necessarily need to relive it.”

DePodesta was energetic and engaging in his interview with Nautilus. He talked about his breakthroughs with the A’s and misperceptions about Moneyball, a hopeful future for the Mets, and how steroids have played havoc with his player analysis.

You’re portrayed in Moneyball as turning to statistical analysis to upend conventional wisdom in baseball. Was that your goal?

I have to be honest with you: that wasn’t the goal. When we started, our philosophy was born out of necessity. The A’s were a team with very few resources. We didn’t have access to players who were obviously great, who could do it all and were always in the headlines. We couldn’t afford those types of players. So we had to figure out a way of cobbling together players into a team that might be competitive. We started looking into various ways of analyzing players and trying to find where the value was. If you had told me 15 years ago that television broadcasts would have OPS1 on them, I would’ve said there’s no way!

Still, did you think conventional analysis obscured the value of players?

Sure, absolutely. We had to take a step back and say, okay, everything we think we know about the game, everything we think makes a championship game or championship player, all the clichés we’ve grown up with since we played our first T-ball game, we want to start over. Unless an idea or a concept holds relevancy in today’s game, under today’s circumstances, then we have to be willing to not believe it anymore. So we’re going to study it rigorously. And some of the old beliefs did hold water. But a fair number of them didn’t. As the game had changed, these beliefs hadn’t changed with it. And that provided opportunities for us. One simple example was batting average. Being a .300 hitter was the benchmark. But was even that relevant anymore?

When would a .300 hitter not be relevant?

To take it to an extreme, a .300 hitter who only hit singles and never walked once all year would be a below average offensive player. It’s not that batting average wasn’t important, it was that batting average was only a slice of the equation.

One cliché is the “five-tool player,” a player who can hit for average and power, and run, field, and throw like a demon. You still hear it all the time.

Right. And everyone wants five-tool players. There’s just very few of them on the planet! But virtually every player has one tool. So we started saying, “Well, let’s investigate each player’s strength. Is there a way to combine all these strengths and cover up some of their deficiencies? We’re not going to be able to do away with their deficiencies. But as a team, can we do it all?” It was about piecing together players we had on our roster and building a team that could do everything. You had to find value where it wasn’t readily apparent.

So it’s really the desire to win that advanced the statistical science of baseball.

No question. Well, the only question is whether we advanced it [laughs]. But our motivation was to win. People have asked me about the winning streak since the movie came out and popularized it. [The A’s won a record-setting 20 games in a row in 2002.] When we were going through it, we were concerned about winning that night. We were in a playoff race. We wanted to win our division. I never took the opportunity to step back and say, “Jeez, what does this mean?” It wasn’t until I saw the movie, which put the streak in a historical perspective, where I said, “Wow, I was fortunate to be a part of that.”

Unless an idea or a concept holds relevancy in today’s game, under today’s circumstances, then we have to be willing to not believe it anymore.

The hero of the streak was Scott Hatteberg, who hits a home run to win the 20th game. He’s a key figure in the book and movie because he embodied a veteran seen as unlikely to succeed. Was it your statistical analysis that revived his career and gave him a chance?

You know, I don’t know. I don’t want to take any credit away from Scott because he deserves everything that came to him. He was a very good prospect and got off to a very good start in his career. It’s true that injuries derailed his career. But this is a situation where he did one thing well—he always hit. He was always productive. We tried to put him in a situation to take advantage of those skills. He revived his own career with how productive he was offensively. If he’d have come over to us and not played very well, our analysis wouldn’t have done him any good. But there’s no doubt that our interest in him was largely out of our analysis, and his value wasn’t obvious on the exterior.

Michael Lewis has a nice line: “To the Oakland A’s front office, Hatteberg was a deeply satisfying, scientific discovery.” Do you agree?

Oh, well, sure! But part of that satisfaction is because Scott is one of the best guys in baseball. He’s highly intelligent, he’s got a great sense of humor, he’s incredibly down-to-earth. There are a lot of players who were under the radar who contributed to our success over the years. But because of the type of guy that Scott is, that made it even better. We’d lost Jason Giambi, the American League MVP, and we were looking for a first baseman. And we signed a “non-tender.” A non-tender is a guy whose current team has his rights and they decline to offer him a contract, so they voluntarily make him a free agent. So to lose the American League MVP, and his replacement being a non-tender, who’s never played one inning at first base, was a little outrageous. I remember standing in a parking lot with Billy [Beane] outside of our office building one day, after we had signed Scott, and we were chuckling to ourselves, saying, “Can you believe we’re doing this? I mean, this is out there!”

When you first got to Major League Baseball with the Cleveland Indians, what was the most important principle guiding your analysis of players?

It’s funny, in college, I hadn’t done any kind of real analysis of players. I played football in college and what I really wanted to do was be a football coach. When I was lucky to get an internship with Cleveland, I had no idea about what went on in a baseball front office. The one real job they gave was to chart the pitches of Major League games. I sat behind home plate and recorded every pitch in terms of type, location, and outcome. I was tasked with writing up a report that would go to our Major League coaches to say this is how opposing teams are trying to pitch our hitters, these are how different hitters are approaching our pitchers, these are our tendencies. It was as if I was scouting ourselves, to give us a sense of what our opponents were trying to do to us.

It was about piecing together players we had on our roster and building a team that could do everything. You had to find value where it wasn’t readily apparent.

Were there authors or books who shaped your thinking about baseball?

Yes. But it wasn’t necessarily out of my formal education. The summer after my freshman year at college, I interned in Washington D.C. for Jim Pinkerton. [Pinkerton was a White House analyst for Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush. Today he is an author and panelist on the TV show, Fox News Watch.] On the first day I showed up at the office, Jim gave me $20 and told me to go down to the bookstore, buy a copy of Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, and don’t come back until I finish it. So I did. The thing that struck me about the book was how paradigms change and what needs to change for progress. I also read Peter Drucker—his interesting management-efficiency stuff. I remember Drucker talking about the value question. Very simply put: If we weren’t already doing it this way, is this the way we would start? Jim looked at everything that way. I remember talking to him about the DMV, and him explaining if we weren’t already doing it this way, do you think this is the way we would do it? So he got me thinking that way.

What’s the guiding principle of your work now?

The guiding principle of our work is figuring out a way to deal with uncertainty. That’s what we deal with every day—an uncertain future. What’s going to happen on the next pitch is uncertain. We can’t figure out exactly what’s going to happen, but if we can get our arms around a range of possibilities, that gives us a much better chance to at least make better decisions. We’re still going to be wrong a lot, but hopefully we’re wrong less often now than we were 10 years ago. But we’re never going to be in a situation where our analysis tells us what’s going to happen. These are human beings interacting with one another in a highly stressful situation. So we’re never going to be perfectly predictive. But that’s what makes baseball interesting, makes it emotional.

Do you rely on probability theory, the math of potential outcomes, to help assemble a team?

Absolutely. We use probability theory every day, as it provides a framework for dealing with the uncertainty. The nice thing about baseball is that all of the possible outcomes are known—it’s not quite as messy as the real world. That makes the game an excellent playground for probability.

What statistics are the most important to you?

Well, in the book, Michael talks a lot about on-base percentage. But this isn’t a new idea. Branch Rickey was talking about the importance of on-base percentage over 50 years ago. So a lot of these things weren’t necessarily novel. I guess one of the differences was just how we were employing some of them. And, ultimately, we created our own metrics that we felt were more valuable for our decision processes.

Like what?

I can’t tell you that!

Give me one example.

Well, for instance, one of things we looked at is trying to look at the value of every situation in the game. So what is it worth to have a man on first and nobody out, versus a man on first and one out? Or even more interesting, how about a man on first with nobody out, versus a man on second with one out? So we study those types of things intensely and try to get an understanding of how value is created in a game, and how it was taken away.

So is it better to have a man on first with nobody out, or a man on second with one out?

Sorry, but I have to leave that one open-ended for people. I’m sure they can find the answer somewhere online these days, but I’m not going to share.

Do you ever look at teams or players and think that their success is unlikely?

Oh, absolutely. It’s part of the beauty of what we do. Baseball ultimately is a drama without a script. It’s the original reality TV. Through our analysis, we can get a real handle on what we ought to expect. But reality only happens once.

Have you ever been surprised by a player who outperformed his statistical profile?

Oh, yeah. A main part of our reasoning is to put ourselves in a position to get lucky. With the amount of competition there is in the industry, it’s hard to put together 25 players that are just way better than everybody else. We drafted some college players at Oakland who we knew would probably be Major League players, but there was a limit to how much impact they might have. We had made the mistake of taking what they were then, and projecting it indefinitely into the future. But they got better. Guys like Eric Byrnes and Barry Zito. We had expectations for them; don’t get me wrong. They were talented players, but they made themselves even better.

What do you mean by putting yourself in a position to get lucky?

Failure is a huge part of our industry. The best players fail every day. It’s no different than a championship poker player or a card-counter at the blackjack table. They lose all the time, too, but they put themselves in a position to get lucky by using pot odds or having an idea what’s remaining in the shoe. Over time, they win, even though there are a lot of losses along the way. We try to do the same. We know we’re still going to be wrong often, but we’re at least trying to give ourselves positive odds.

We’re never going to be perfectly predictive. But that’s what makes baseball interesting, makes it emotional.

You’ve said, “We don’t allow ourselves to be victimized by what we see.” What did you mean?

Everyone has a vision about what something is supposed to look like. And because of that there can be confirmation bias. You say a great Major League player is supposed to be 6-foot-2 and 205 pounds, and run like a deer and have a V-shape back. But that can fool you. So we try to get away from that. I’m going to a tournament later today where I’m going to watch four games of high school kids. Now, these kids are going to play a lot of games over the week that I’m not going to see. But the stat sheet is going to be there every single time. So you have to put your faith in analysis, in what you can figure out, as opposed to just what you see with your own eyes. That said, there are certain things that you pick up in person that you can’t see on the stat sheet.

What are you looking for in high school players that you can’t see on the stats sheet?

Physical attributes like quickness or explosiveness or hand-eye coordination. But just as importantly, if not more importantly, are certain mental characteristics: their confidence, how they deal with their teammates, how they interact with their coaches and parents, how hard they play, how much they battle when they’re not just behind in a game but in a count. Or how they react when they get a bad call from the umpire. The minor leagues, and baseball in general, are a real grind, especially for an 18-year-old young man. There are some who are physically gifted and ready to compete physically, but mentally are just not ready for that grind. I think as an industry, we probably make as many mistakes on that front as we do on measuring the physical tools.

Have performance-enhancing drugs affected your statistical analysis of players?

Oh, yes, dramatically. I mean, especially in the first part of last decade. I’m embarrassed to admit how naive we were back then because we didn’t even think about it. Looking back at a lot of those guys, we went, “Oh, my goodness, look at these dramatic changes in performance.” So all those data points get cycled into our algorithm, into our modeling.

So how do you now evaluate players in light of performance-enhancing drugs?

Back in 2004, 2005, when Major League baseball started testing, we all started becoming a little bit more knowledgeable about what was going on in the game. We had some long conversations. Do we just scrap the last 15 or 20 years worth of data and start over? How do we adjust for this? It was a big problem for the latter half of that first decade of the century, from 2005 to 2010. I think since then we’ve got a better handle on how to deal with it, sort of how to adjust for it, and we’ve been able to make some of those numbers work. The moral issues are the bigger ones. But from a practical standpoint it created some big obstacles for us.

Has anyone ever used statistics to systematically prove that players put up better numbers using steroids than not?

I certainly never have. We don’t know everyone who was using, we don’t know when, and we don’t know what else they were doing. With players who have been found to be guilty, we’ve looked back and tried to see what happened with their performance, to have a better understanding of it. But again, those are really just anecdotal examples and can be dangerous.

We had some long conversations. Do we just scrap the last 15 or 20 years worth of data and start over? How do we adjust for this?

You’ve been with the Mets for almost three years. Given your statistical and scouting acumen, why do the Mets, if I can play the cynic for a minute, have a below-.500 average during that time?

It’s a fair question. I think a lot of it just has to do with time. And also just what’s available out there, and what flexibility you have to pursue what’s out there. But we feel that we’re getting closer to where we want to be. Four years ago, at the minor league level, from Low A up to Triple A, our clubs were under .500. As we sit here today, we have the best record in minor league baseball. Now, winning at the minor league level isn’t necessarily a goal, and it’s certainly not the definitive harbinger of success at the Major League level. And that’s ultimately what we’re there for: success at the Major League level. But I do think it’s an indication that progress is being made, that we have more productive players who hopefully, eventually will impact our Major League team.

Do you think statistical analyses like yours have changed baseball?

Well, there’s a lot more scrutiny on transactions and signings. By and large as an industry, we’re probably more discerning than we were 15 or 20 years ago.

Do you think fans see that on the field?

Probably not. Put it this way: It’s not the only way of doing things. There have been some very successful teams that do it differently. It still boils down to the competition on a daily basis, and that’s what the fans see on the field. There is a good measure of competitive balance in today’s game that was more difficult to come by in the late ‘90s. Team revenues are still far apart. And that still has an impact. But I do think some of this analysis has leveled the playing field.

Footnote

1. OPS (on-base plus slugging) is a sum of “on-base percentage” and “slugging percentage.” It’s designed to reveal more about a hitter’s value than traditional statistics like batting average (how often a player gets a hit per at bat) or RBI (how many runs a player drives in). In a glance it characterizes a batter’s ability to both get on base and hit for power, key factors in creating and scoring runs, prized possessions of any hitter.

On its own, on-base percentage marks how often a hitter gets on base per at bat by either a hit, base on balls, hit-by-a-pitch, or sacrifice fly. Getting on base via a fielder’s error, for instance, doesn’t count. The calculation for OBP goes like this:

OBP = H + BB + HBP

AB + BB + SF + HBP

H = Hits, BB = Base on balls, HBP = Hit by pitch, AB = At bats, SF = Sacrifice flies

Slugging percentage, meanwhile, is a picture of a player’s value as a power hitter. Again, it’s designed to tell more about a player than common statistics like batting average or RBI. Batting average, for instance, only indicates how many hits a player gets per at bat. But each hit is not created equal. A single is not worth as much as a double or a triple, which advance players further around the bases, increasing their odds to score. Slugging percentage accounts for a hitter’s extra-base hits, or those other than singles. The calculation goes like this:

SLG = Total Bases

AB

Total Bases = Hits + 2B + (3B x 2) + (HR x 3)

2B = double, 3B = triple, HR = Home Run

So add up on-base percentage and slugging percentage and you have a multidimensional look at a hitter’s worth. The final OPS calculation would look like this:

OPS = AB * (H + BB + HBP) + TB(AB + BB + SF + HBP)

AB * (AB + BB + SF + HBP)

The hitter with the all-time highest OPS is, no surprise, Babe Ruth, whose OPS, over his career, is 1.164. Ted Williams is second with 1.116. Recently, the hitter with highest OPS is Detroit Tigers superstar Miguel Cabrera. From July 2012 to July 2013, Cabrera’s OPS is 1.105.