Marc Feldman has spent more than 25 years studying fakes, but the bespectacled Alabama-based psychiatrist still vividly recalls the woman who introduced him to what became his life’s work. It was in the early 1990s, when he was a newly minted psychiatrist, shortly after completing his residency at Duke University. His department chair asked him to see a patient he calls “Anna,” who was suffering from an unusual psychological disorder.

The woman sitting in the brightly lit exam room was emaciated, and her gaunt body was virtually devoid of flesh with an ill-fitting brown wig sitting on her shaved head. She was in her 30s and had been employed in a position of some responsibility. Anna’s alarming appearance was presumably the result of several grueling rounds of chemotherapy for her metastatic breast cancer, which had sucked about 60 pounds off her frail frame and caused her hair to fall out.

Except that it was all a lie. For nearly two years, Anna had pretended to be sick: She copied the cancer symptoms of an acquaintance, starved herself to shed weight, and shaved her head to mimic the appearance of undergoing treatment. In a case report, Feldman and his co-author Rodrigo Escalona noted that Anna refused social invitations, fearing her vigilance would falter and she’d give the ruse away by acting “too well.”

The words that came tearfully tumbling out to explain what motivated her to fabricate such an elaborate ruse had a certain twisted logic. A few years before, her fiancé had abruptly ended their engagement, which left her feeling abandoned and betrayed. Soon after, she told coworkers about her “breast cancer diagnosis” and that her prognosis was grim. Their outpouring of sympathy filled the profound emptiness in her life, which had become more pronounced after her broken engagement. Their warmth and concern prompted her to join a cancer support group, where she quickly established a network of close friends, even though it had been difficult for her to form deep relationships.

But her deception was discovered when the leader of the support group, in a routine review of her medical chart, found out Anna had never seen the oncologist she claimed had treated her. Confronted with the truth, she confessed—and was promptly fired when she told her irate employer. Distraught, Anna realized she needed help, which is how she ended up in a psychiatric ward diagnosed with Munchausen syndrome, a condition in which people feign illness or make themselves sick.

Because of easy medical access online, Munchausen syndrome is now more common than it’s ever been.

“I didn’t know anything about Munchausen, I didn’t even know the term,” Feldman says. “These stories and lives are jaw-dropping; it’s almost impossible to get bored.” He has since become perhaps the world’s leading expert on Munchausen syndrome, and has written four books on these great pretenders, most recently Playing Sick? Untangling the Web of Munchausen. Over the years, the soft-spoken physician has treated numerous patients and received hundreds of letters and emails from people suffering from or victimized by this little understood disorder.

Only about 1 percent of hospitalized patients are fakers, according to estimates by the Cleveland Clinic, although that would translate to hundreds of thousands of cases in the United States alone, given that hospitals treat more than 35 million people a year. Feldman suspects the true number is higher because physicians often don’t realize they’re being duped, especially since “patients” hop from one doctor to another to avoid exposure. “Doctors often do know, but don’t confront the patient for fear of the consequences,” he says. They worry about being sued for malpractice or defamation or being bad-mouthed as insensitive, so they try to protect themselves by referring patients elsewhere.

More recently, Feldman has worked with people suffering from what he calls Munchausen by Internet. “It used to be that people had to go from emergency room to emergency room, they would have to study up on illness and try to appear authentic when they were faking,” he says. “Now all you have to do is sit at home in your pajamas and click into a support group and make up a story.” Because of this, Feldman suspects Munchausen syndrome is now “more common than it’s ever been.”

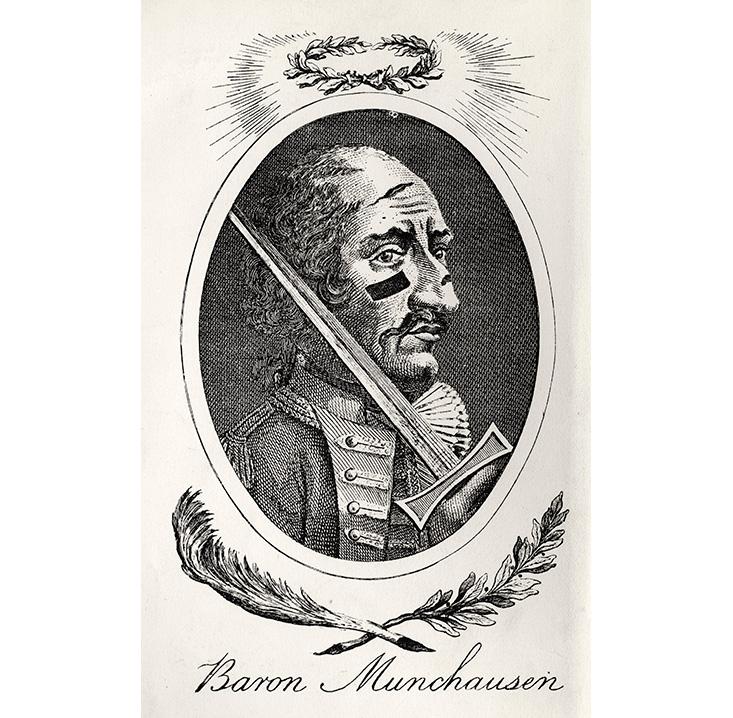

The term Munchausen syndrome was coined by psychiatrists in 1951, after Baron von Munchausen, a German soldier who told fanciful tales about his adventures. It’s not the same as hypochondria, because hypochondriacs truly believe they’re sick. Munchausen patients know they’re lying and often go to extraordinary lengths to fabricate symptoms, such as injecting themselves with bacteria or household cleansers, or undergoing serious surgeries and other procedures that can cause permanent injury.

The impulses that drive people to concoct these elaborate ruses are, in many ways, perverse extensions of the craving for attention and affirmation. “Many patients with Munchausen syndrome pretend to be ill because they feel this is the only way anyone will pay attention to them,” says Gregory P. Yates, a researcher at King’s College in London, who is collaborating with Feldman on a book to be called The Mystery of Illness Deception.1 “They believe that having an illness will make them feel special. Patients who are diagnosed with Munchausen syndrome are almost always found to be struggling with something—perhaps depression or a traumatic childhood. They need help. But for whatever reason, they cannot admit this to others and so they use illness as an excuse to reach out for emotional support.”

To help us understand the destructive syndrome, Feldman agreed to share his experiences with five of his Munchausen patients. Recovery from Munchausen is rare because patients usually refuse to admit to their lies or cooperate with psychological evaluations. Most of Feldman’s Munchausen patients are women. “Male Munchausen patients almost never come forward and avail themselves of psychiatric care,” he says. Because of Feldman’s close experiences with Munchausen patients, we asked him to recount each case in his own words. The accounts below are drawn from interviews with Feldman and a selection of his published works (listed below). With the exception of Wendy Scott, the names of the patients have been changed to shield their identities.

Wendy: Hospital Hobo

Wendy Scott was fed up working as a hotel maid. Guests and hotel staffers ignored her and the menial job itself made her feel worthless. One of the few enjoyable experiences she remembered from her adolescence was having her appendix removed when she was 16. This chance contact with the medical profession was unexpectedly gratifying. “It was the first time anyone asked me how I was feeling,” she told me. “I had no responsibilities and no one was barking orders.”

So Wendy pretended she had a stomachache and checked herself into the local hospital to escape the grinding misery of her daily routine. Sure enough, the doctors and nurses gave her the care and consideration that was so sorely lacking in her life. For the next dozen years, Wendy was itinerant and homeless, isolated from her family and friendless, traveling from one hospital to another throughout her native Scotland and England, and then other countries, looking for a safe haven. “Everyone understands the universal language of ‘ouch,’ ” she told me later, when she became my patient, in a rather unnerving explanation of how easy it was to fake it, even when there were language barriers.

Baffled physicians suggested exploratory surgeries, in hopes of figuring out exactly what was wrong with her. Wendy ultimately underwent 42 procedures—none of which did any good. Sometimes, though, the hospital staff got suspicious, forcing her to flee, even with stitches still in place. She ultimately developed fistulas, which are gaping holes in her intestines. A few of these injuries stemmed from physician error because it’s easy to nick the bowel when surgeons are forced to tease apart all the scar tissue from previous surgeries. But sometimes, the wounds happened because she skipped out of hospitals while still recovering from these invasive procedures—and foreign bodies like stitches are prone to infection—and failed to comply with the full course of treatment.

By her own admission, Wendy was hospitalized 800 times at 650 hospitals throughout Britain, Europe, and Scandinavia, making her perhaps the most severe case of Munchausen’s I had ever encountered. But the roots of her disorder were readily apparent: Her desolate childhood growing up in a working class town in Scotland was punctuated by repeated sexual abuse by her stepfather. She ran away after each episode but eventually ended up in a home for wayward girls. Afterward, Wendy worked at a series of menial jobs—at a dairy, a bakery, a potato farm, and as a hotel maid—that she felt were soul crushing. Being in a hospital, where people were kind and she felt valued, was a welcome respite from her lonely life.

She was forced to flee on a moment’s notice when the staff got suspicious, even with stitches still in place.

But when one surgery went terribly wrong, causing infections and serious complications that almost killed her, she finally stopped her lies. She found recovery in an unlikely place: a homeless shelter in London, where she was supported by the staff and formed her first real friendships with the other residents who also lived on the fringes of society. She adopted an abandoned kitten that she named Tiggy, and understood that if she gave in to her impulses, her beloved pet would have to fend for herself. Gradually, she got better. Her personal family of strays grew to several cats and dogs, she found work at the London Zoo, a good spot for an animal lover, and counseled others suffering from factitious disorders.

But 20 years later, when she was genuinely stricken with a life-threatening illness, no one took her complaints seriously. After suffering from severe abdominal pains for nearly two years, some physicians saw the mass in her abdomen but they were too wary of her past. The scars all over her body, on her stomach and arms and legs from the surgeries and the constant blood draws, were telltale giveaways to doctors that she was on the “Munch Bunch” black list common in British hospitals.

Wendy was wheelchair bound when we first met in Birmingham, Alabama, where I was the medical director at the University of Alabama’s psychiatric center. She was a thin woman with long brown hair streaked with gray who wore no makeup and spoke with a lilting Scottish brogue. I hugged her and she smiled weakly but it was clearly difficult for her to do. Wendy was around 50 at the time, but her face was heavily creased and care-worn. She was genuinely sick, perspiring profusely and wracked with excruciating pain.

I sent her to the emergency room where tests revealed she had advanced colon cancer. The tumor inside her abdomen was the size of a small soccer ball and it took surgeons more than two hours to cut through all the scar tissue before they could get close to the malignant growth. The cancer was everywhere. She spent four months in the hospital in Birmingham, undergoing chemo and radiation, before returning to London, still feisty as ever. But she died in hospice two weeks later and was cremated. Her ashes were spread on the street near the homeless shelter that had given her a second chance at life.

Luther: “I Thought That I Was Just Evil”

In 1995, I received a letter from a distraught mother who was completely baffled by her 18-year-old son’s behavior. The medical records that she sent along with her letter attested to the severity of his illness. Since Luther entered adolescence, his once mild case of asthma had worsened dramatically to the point where he was on a daily regimen of steroids to throttle symptoms and which forced him to be home-schooled because she never knew when he would have a life-threatening attack. At least three to four times a week, he was ushered by ambulance to the local emergency room because his wheezing became intractable. Their lives were circumscribed by his attacks and, later on, his seizures.

One day, the pair had been flying from their home on the East Coast to Denver, where he was scheduled to see a team of specialists at the National Jewish Hospital, a world-renowned facility for treating respiratory disorders, to find a way to control his severe asthma. But mid-flight, Luther had a life-threatening attack—he began wheezing and was unable to catch his breath. His inhaler proved useless and his lips were turning blue, which is a sign of choking and asphyxiation. Frantic, the mother alerted the flight attendant and the plane made an emergency landing at an airport. An ambulance was waiting on the tarmac and sirens blared as they sped through traffic, rushing him to the hospital.

But once his condition was stabilized and he was transferred to the hospital in Denver, he made a shocking confession: It was all an act. All of it—the asthma attacks, the seizures. Everything. He even admitted to slathering his lips with blue eye shadow to make it look like they were turning blue. His mother was dumbstruck and struggled to understand why her son would engage in such elaborate, destructive, and costly fabrications.

In subsequent correspondences with her and with Luther, I began to piece together what might have instigated this behavior. His father was a composer of hit pop songs and the family lived in an upscale suburb. Entering puberty was pivotal for Luther, a period in which he was coming to terms with his own sexuality and with the realization he was gay at a time when it wasn’t as socially acceptable as it is today. Intellectually gifted and medically astute, he invented the escalating asthma attacks and other contrived illnesses, which were so easy to fake, as a way of competing with a highly successful father and monopolizing his mother’s attention and affections. He became, in short, a sickly adolescent requiring constant care.

He admitted to slathering his lips with blue eye shadow to make it look like they were turning blue.

I saw a tape from his Bar Mitzvah when he was 13, before all this started. In the video, Luther was this skinny, handsome kid and he performed admirably. I couldn’t believe it was the same person. Because of all the steroidal medications, he had become a morbidly obese young man with a moon-shaped face. He had severe acne, and he developed a dowager’s hump that resembled someone with Cushing’s disease. There was no remnant of the old Luther any longer—he was encased by his obesity. But he felt he had no other choice—he knew what he was doing wasn’t good but he felt compelled to do it. Later on, after he learned about Munchausen syndrome, he said, “I was shocked that they had a name for what I was doing. I thought that I was just evil. I thought that I had been possessed by some spirit.”

One of the bitter ironies of this disorder is that even though it’s intended to be a strategy to gain control, as Luther discovered, it eventually robs sufferers of control over the behaviors that wreck their lives. “I had no friends when I was sick with Munchausen because that becomes your friend,” he told me. “Disease is your friend, it’s your lover, it’s your enemy, it’s your mother, it’s everything to you. Only after I turned my back on it did I form real friendships.”

Melissa: Fooling Doctors

After the birth of her first child when she was 24, Melissa sank into a deep postpartum depression. The new mother was so consumed by suicidal thoughts and psychotic hallucinatory episodes that she was committed to a psychiatric ward. But the hospital turned out to be a sanctuary for her. In a narrative she wrote about her disorder, she said the admission “gave me relief from the overwhelming obligations of being a new parent. I found being sick in the hospital felt like a dream come true.”

Melissa wanted to prolong the experience. She had struggled since she was 11 with thoughts of faking fainting spells. They had become an obsession throughout her adolescence and young adulthood and distracted her from her schoolwork and socializing with friends. She was ashamed of these fantasies and told no one. But once she was in the mental ward, she found a way to unleash all these pent-up desires and indulge her secret yearnings.

Melissa spent her time in the hospital’s medical library, boning up on psychiatric illnesses she could portray. In her narrative, she said she had spent an afternoon with a person with schizophrenia who had a distorted view of reality and spoke in word salad. She trained herself to mimic his odd behavior and disjointed speech patterns. She devoured medical texts, memorizing the symptoms of various diseases, and read articles that described how to detect if a patient is faking. She even trained herself to urinate during a “seizure” or restrain her reflexes when she was “paralyzed” to outwit doctors.

Melissa also made her first tentative forays into faking physical symptoms. She would show up at the emergency room complaining of abdominal pains but sometimes would run away because she was too scared to carry out her ruse. Gradually, she became more confident and skilled at her deceptions, gaining admissions to hospitals even though she knew it was wrong to trick people who were honestly trying to help her. “I felt I had no other choice,” she wrote. “Sometimes it was that or suicide.”

But her repeated absences took a toll on her family. Her husband divorced her and kept the children. Melissa was bereft at the loss, but frankly admitted the breakup freed her to wander all over the country gaining admission to hospitals more than 100 times over the next seven years. She got radiation sickness from all the X-rays and was fired from jobs—even though, according to her, she was an otherwise exemplary employee—because she missed so many days of work after spending weekends in the hospital. But her disordered behavior was addictive, and like a drug, it was too gratifying to stop. “While I’m in the emergency room and all those medical personnel are bustling around me, making sure I don’t die, I feel safe and I just want to sink into their arms and take all that attention in,” she wrote.

The gamut of illnesses she was able to fake was astonishing, ranging from stroke, multiple sclerosis, Guillain-Barre syndrome and epilepsy to psychosis, schizophrenia and dissociative identity disorder, in which patients switch between multiple distinct identities. She even feigned deaf-mutism and was so convincing that she showed me the transcript of the communications she had with one of her doctors. “Sometimes I would fake a physical illness and just when I was about to be caught,” she wrote, “I would present psychological symptoms and get transferred to the psychiatric ward.”

Melissa is highly intelligent and well educated, and discussions with her provide a window into the psychological makeup of people who fake illness and the motivations behind her deceptions. She was intoxicated by her ability to fool doctors. It gave her a sense of control and superiority, and a great deal of satisfaction of being able to outsmart them, which put her on an equal footing with respected professionals. She confessed to always being a goody-goody, even as an adolescent, but living a lie was a form of rebellion, making her more interesting to others. Carrying off the deception provided an escape from the boredom of daily life and a safety valve for her extreme anxiety. She wrote that “entering the hospital, I feel the pressure of anxiety relieved like after sex. The anxiety builds up over time so that I feel I need a great release or I will become completely nonfunctioning, become psychotic, or kill myself.”

Melissa has remained closeted—no one in her community in the Pacific Northwest knows—and she made sure there was always one doctor and one hospital where she never faked so she would have a place to go to if she became genuinely ill. With the aid of intensive psychotherapy, Melissa overcame her obsession. Since the worst of her Munchausen days, she returned to school and got a decent job and was able to raise her children full time throughout their teens. She also became a patient advocate, even winning awards for her volunteer work, although none are aware that she’s speaking from her own hospitalization experiences as a great pretender.

Nellie: At Death’s Door

Nellie had been institutionalized when she was in elementary school when she burned her house down. Psychiatrists locked her up to keep the family safe—although she says she set the fire to somehow bring her family together. Even as a child, she felt a deep need for affection that was not being met and her feelings of isolation and abandonment were intensified in the psychiatric facility where she experienced physical and emotional abuse. As she wrote in an account for me, “It started in my teens when I secretly caused chemical burns on my arms with oven cleaner and drank juice mixed with kitchen cleansers.” Her behavior was to avoid the sexual abuse she claims to have endured. “When I was sick, my abusers would leave me alone,” she wrote.

Her self-harm escalated into a full-blown pathology when she was 18. She was hospitalized when she was in a car accident, and suddenly discovered how much unconditional love she received while she was recovering. After that, most of her attention was focused on injuring herself so she could be hospitalized. She would go to great lengths to feign illness, such as injecting herself with feces to cause infections, exposing herself to bitter cold to become frost bitten, lacerating her vagina, swallowing detergents, or adding blood to urine samples to cause abnormal test results.

Over the years, she was hospitalized 30 to 40 times, had countless surgeries and diagnostic procedures and prescribed hundreds of medications. She frequently dropped out of college because she was so busy being sick and she was forced to declare bankruptcy because of the astronomical medical bills—topping more than $400,000, which she incurred when she had no health insurance. But her hazardous behavior finally caught up with her, causing a permanent injury. Nellie had to have her bladder removed after injecting her bladder with drain cleaner; the external urinary bag a constant reminder of the depths of her self-inflicted damage. Still, harming herself remained her only means of survival. “Being sick had become a way of life and I was unable to stop,” Nellie wrote. “The rewards were just too great.”

She would go to great lengths to feign illness, such as injecting herself with feces to cause infections.

One day she ended up in the ICU after she injected feces into her bloodstream. Except this time was different: She went into septic shock. While she was in the ICU, Nellie vowed that if she recovered, she would tell her doctor the truth: that she had spent the better part of the previous two decades making herself sick. “For the first time, I found myself really scared that I might die,” she said. The shame and humiliation she experienced after her revelation fueled her decision to start fresh somewhere else, and she moved from the Midwest to Birmingham, Alabama to become my patient. “I lost the support of nearly all my friends and family when they realized I had deceived them,” she told me. “I didn’t stop until I realized, through therapy, that there were reliable and safe ways to meet my need to be cared about. I used to think that my ruses were the answer to my problems. Now I realize that they only created more problems and solved nothing.”

Nellie is a rarity. After years of psychotherapy and becoming a born-again Christian, which she felt was pivotal to her recovery because it provided her with a caring support network, she has gone on to lead a happy and productive life. During her psychotherapy, she went back to school and was named employee of the year at a job. She graduated first in her class and became a healthcare assistant.

Helen: Feigning Cancer Online

Helen turned to an online support community when she had been suffering from severe abdominal pains and was concerned that she might have ovarian cancer. Her initial motivation in joining the group was innocent. But once she experienced the warm reception from the community members, she began weaving tall tales. First, she created the persona of Isabelle, who introduced herself as Helen’s friend and had some terrible news: Helen had fallen into a coma. Group members responded with expressions of sympathy and compassion. This prompted Helen to create a storyline involving this character, culminating with Isabelle’s announcement that she had been diagnosed with stage 4 gastric cancer and that she was failing fast. Then Isabelle introduced her boyfriend, Justin, to the support group so he could supply updates on her illness. Ultimately, she died, and Justin became seriously ill, too, and conversed extensively with other group members about his grief over Isabelle’s death and his own rapidly deteriorating health. Helen then chronicled Justin’s death, and introduced two new characters, Justin’s father and sister, to continue the story.

While the essential dynamics of Munchausen are at play here, individuals who engage in Munchausen by Internet take it one step further. They victimize the emotionally vulnerable—real patients who use online forums to cope with their own serious illnesses and have deep empathy for others in similar circumstances. In looking critically at Helen’s story, it seems preposterous that anyone would believe her extravagant lies. No one’s luck is that bad. But over a year period, people in the support group became invested and for some of them, the Internet is their lifeline to a broader social community that they don’t feel they have the skills to develop on their own. Their continued involvement, even in the face of ever more outlandish stories, speaks to their own personal needs and their gullibility and codependency. Some of them spent many hours every day engaged with these fictitious personalities, all time that has been wasted. When they finally realize they’ve been duped, they feel ripped off.

Helen carried on this complex ruse for nearly a year, until she learned of Munchausen’s by Internet when it was brought up in a group discussion. After researching the diagnosis and recognizing that she fit the description, she posted a confession on the support group’s website, even offering her real name and phone number, and expressed deep remorse for her actions. She also told them she intended to seek psychotherapy to “put all of this behavior behind me”—and reached out to me. Helen is another success story: She recently started a bakery business, selling her confections online, and to the best of my knowledge, she has remained free of all Munchausen by Internet behaviors.

Linda Marsa is a Los Angeles-based science and medical journalist and a contributing editor to Discover.

References

Feldman, M.D. & Escalona, R. The longing for nurturance: A case of factitious cancer. Psychosomatics 32, 226-228 (1991).

Feldman, M.D. Breaking the silence of factitious disorder. Southern Medical Journal 91, 41-42 (1998).

Feldman, M.D. Playing Sick: Untangling the Web of Munchausen Syndrome, Munchausen by Proxy, Malingering, and Factitious Disorder Routledge, New York, NY (2004).

Feldman, M.D. Recovery from Munchausen syndrome. Southern Medical Journal 99, 1398-1399 (2007).

Cunningham, J.M. & Feldman, M.D. Munchausen by Internet: Current perspectives and three new cases. Psychosomatics 52, 185-189 (2011).