Imagine a top turning and turning in a widening gyre, like a dancer without a partner, its spin axis wobbling as though it were under the influence. What keeps that top going round and round in hypnotic whorls is a force called angular momentum, a challenge to the leaden tugs of inertia and gravity. Angular momentum is a property fundamental to spinning objects at all scales of the universe, from planetary motions and galactic spirals to tides and light waves, to the tiniest quantum particles that blink in and out of existence.

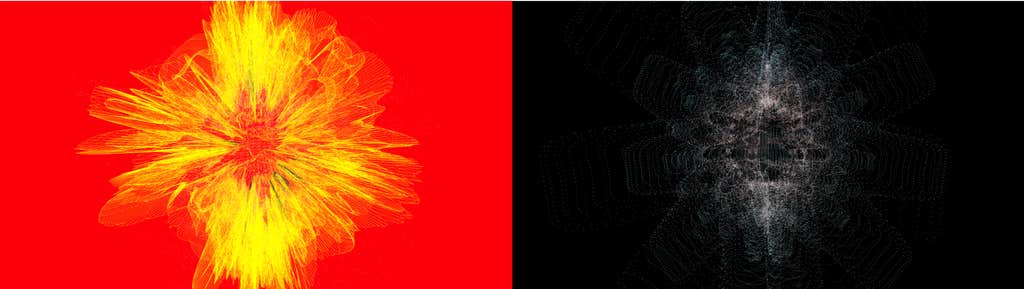

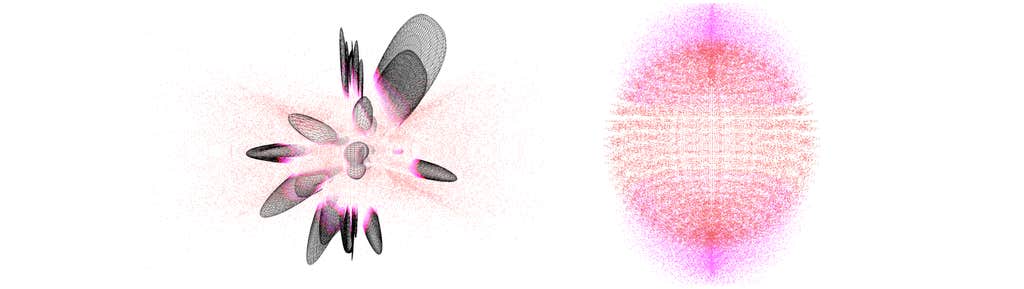

It also propelled the creation of Angular Momentum, an art show by Brooklyn-based artists Chris Klapper and Patrick Gallagher currently on exhibit at the art gallery at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Batavia, Illinois. The show explores the mysteries of infinitesimal energies and spinning particles in the quantum world.

The artists took inspiration from an early 2020 artist residency at Fermilab, where they collaborated with scientists working on the Muon g-2 experiment. In that experiment, the physicists set out to measure the spins of elusive particles called muons—which exist for only a fraction of a second—with tremendous precision, equivalent to gauging the length of a football field in increments of one-tenth the thickness of a human hair. The findings have implications for whether the standard model of physics is sufficient to explain the universe.

Klapper and Gallagher, long-time collaborators and spouses, spent two weeks working with physicists in Fermilab, including the scientist who was running the muon experiment, Adam Lyons. “He blew our minds,” says Klapper. “We were just like, ‘We wanna talk to you for hours.’” Then the pandemic hit, so they had to move these heady conversations over to Zoom.

The artists say the scientists made the concepts easy to understand, though it helps that the pair already knew a bit about particle physics from other installation pieces they have created over the past decade—and that they recently began studying higher mathematics together. “We were like, ‘Really, let’s nerd out!’” says Klapper.

The artworks in the show, which include videos and digital prints on aluminum, were created using a software program the artists designed to visualize interacting spheres with electromagnetic frequencies. (The full series is on Klapper’s website.)

We spoke with Klapper and Gallagher about the art, the inspiration and their journey into the world of subatomic particles.

What is angular momentum?

Patrick Gallagher: Everything in the quantum world has angular momentum. Things spin but not in the way we typically think about spin. We have this idea of the model of an atom, with the nucleus and the electrons spinning around it like orbiting planets. But what we found out when we got involved with this project is that these spins are more of a frequency, and the rotations and orbits are more three dimensional, and they create interference patterns, and those interference patterns become these particles like the muon.

Chris Klapper: And they can detect those particles because when they spin, they have a different kind of charge.

It’s a very poetic dance between the particles as they’re moving and changing and affecting each other in these oscillations and we wanted to take that and make it into artwork. We like to take these immense ideas and express them on a human scale. We think of ourselves as translators. If you can show someone who doesn’t know anything about particle physics something beautiful, that might trigger them to go, “Ooh, I wanna learn more about this.” We want to inspire people to follow their own little rabbit holes, to embark on this incredible journey of studying the language of the universe.

What appealed to you about the muon project?

Gallagher: One thing really stood out as we were learning more about the muon project. The Earth and plants and everything on the macro scale, we think about that as nature. But as we get smaller, it’s like, “Oh, that’s not nature. That’s chemistry.” Or, “Oh, that’s not nature. That’s physics. That’s something else, completely different.” But it’s alive. There really isn’t any other way to grasp it down at that level. There are forces and energies and interactions that are happening, and it’s completely mysterious. And that was what our series tries to show, that the structures at that scale are phenomenally complex. You would think as we’re getting smaller and smaller, the elements of the universe would start to get simpler.

Klapper: People have asked us, “How do you find inspiration in math and science?” And it’s like, this is everything, all the language of the universe. All the physicists are doing is studying what we are, where we came from, where we’re going, everything about life. And there’s nothing more inspiring than life.

What was your process for making the actual works?

Gallagher: When we landed on angular momentum, we were trying to think of how we could visualize it. So we built a mathematical program that would allow us to take a set of concentric spheres and give their surfaces electromagnetic frequencies. And then we tried to imagine what it would be like if the interactions between the spheres were happening at the speed of light over incredibly tiny spaces. What if we were able to slow that down and also zoom into these particles and try to show what it looks like when they’re actually interacting? And our program allowed us to do that.

Klapper: It allowed us to simulate how these particles would interact and what that interaction would look like, and how they would oscillate. Like the one sphere’s oscillation would affect the other sphere’s oscillation. So this was a virtual space where we could apply our artistic language.

Gallagher: An easy way to think about how the spheres interact is to consider what happens when you throw a stone into a pond. If you throw a couple of stones, the resulting ripples meet and intersect and create new patterns and harmonics. This is happening on a 3-D scale though, not a flat surface, and that’s what this work is really about. When the harmonics and ripples interact with each other, they create these interference patterns. And as far as quantum physics goes, all of the particles are made by these odd energies interacting and creating patterns. It’s impossible not to also come out of the study of quantum physics without some deep philosophical questions.

What kinds of philosophical questions come to your mind?

Gallagher: Well, we’re not really sure if the lower subatomic particles necessarily exist. There’s quantum field theory, which is slightly different from quantum mechanics, which says that all of these particles only exist when they interact.

And so what is reality if a lot of these particles will disappear? They’ll come back, but it’s not the same ones. So I think philosophically it gets to what is our reality when we’re looking at this?

Klapper: We’re all made of energy. I think so many people think, “Well, I am this and you are that,” but we’re actually all one thing because we are all energy. I mean, we’re pretty much made of the same thing as the chair and the table and the computer. The same stuff, we’re just put together in a different way. And so that is another kind of question. It’s like, “What, then, is reality? And where do I stop?”

Gallagher: That’s the exciting part. That’s the inspiring part as well, because there are so many questions. It’s so interconnected on the human scale. And then to see that it’s even more interconnected on the quantum scale really makes you think about what our place is in the world and in reality. ![]()

Angular Momentum runs through September 3, 2024, at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Batavia, Illinois.

Lead image: This artwork, L=resonance, is featured in Angular Momentum and was provided by Chris Klapper and Patrick Gallagher.