Populated by weary humans and their robot helpers, the world of Helen Phillips’ latest novel Hum is set at some unspecified time in the future, but it feels disturbingly contemporary. Her protagonists are a family burdened with economic and existential disappointment. The parents struggle to keep afloat financially, while navigating their children’s ever-deepening relationships with their devices. Climate catastrophe is often just around the corner or has already happened or both: The family seems to be forever recovering from one calamity while preparing for the next. Advertising is relentless and inescapable, and the surveillance state is status quo.

“You are unsure how to be in the world as it is now,” says Phillips’ protagonist, May, the mother of the family, to herself. “You know the world is damaged, but you don’t know what that means for the lives of your children.” And this concern lies at the heart of the book: that though we know we are passing a dire future down to upcoming generations we don’t know how to stop it or what that future will look like.

I spoke with Phillips via Zoom about this and other keep-you-up-at-night themes written into Hum, her third novel, which like her previous works, takes a speculative, thrilling look at how families cope with a rapidly changing world. We chatted about technology’s threat to human connection, the research she did while writing the book, the uncertain line between utopia and dystopia, and whether there’s anything we can do to tip the balance in favor of the former.

Where did the idea for Hum originate?

I was walking home from work one day some years ago when the thought crossed my mind: I need new dish rags. Just an idle thought. And then, when I got home, I opened my computer and dish rags were advertised to me. It was just one of those moments—and I think we all have them now—where it's like, Wait! How did it know I wanted that? It was internal, but somehow there was some external marker they picked up on. And so this moment was very striking to me, and I went ahead and bought whatever dish rags were advertised.

So that got me thinking—it feels uncomfortable, it feels uncanny to have a little desire or need made manifest when you feel like it was just in your mind. It's maybe not such a big deal when it's just dish rags, but it still feels uncomfortable. It feels like there's something not right about that. And with the book I wanted to ask the question, what would be the worst case scenario for this, the worst thing that could result from having these things that you feel privately made public?

“Hum” is the most sacred sound of the universe.

You have said elsewhere that your inspiration often comes from imagining a nightmare version of a familiar world, and peeling back the surface to see what’s underneath. What appeals to you about these kinds of scenarios?

One reviewer described my book as being set five minutes in the future, and I appreciated that description. My hope is that my books will enable people to feel less alone in really looking at the things in contemporary society that are producing anxiety. This book is speculative fiction, but as you may note from the bibliography, it is very much drawn from our world. When you look at something that is a little speculative or a little weird or a little different, it enables you to see your own reality anew.

I really liked the word “hum,” as both the title and the designation for the AIs. Where did that idea come from?

I love the sound of that word, hum! It’s the constant background sound made by machines. It's related to the word human. It feels derived from that. It’s the most sacred sound of the universe, a sound we can associate with being sung to as a child. So it came to me very organically and very early on.

In the world of Hum, things that the characters don't really need are cheap, while the things that they actually do need, such as rent or access to nature, are expensive. What are the consequences of this dichotomy?

In the novel, the highest tech devices are accessible and subsidized even for a family that's encountered some financial problems, because our attention is so valuable to advertisers that they are willing to give us these gadgets for free. In exchange we give them our attention, which feels like this free thing that you just have, but is actually, perhaps, your most precious resource. We kind of take that for granted, but our attention is very valuable to advertisers, and it should be even more valuable to ourselves.

Do you think there's always a clear line between dystopia and utopia?

No, I don't think there is. Even on this planet of ours, there are people living a pretty utopian version of this technological and climate change experience, and then there are people who are living a very dystopian version of that. It's definitely not a straightforward thing. At the center of the book, there is a utopian setting that this family gets to enter for a time, and that utopian setting is hopefully as much of a refuge for the reader as it is for the family. But then it also proves to have a much darker side, as I think any utopia does.

When I set out to write this book, it was important to me not to evoke a sheer dystopia. I don't know if I've succeeded or not. I wanted to have within the book—and within myself and my own inquiry as I was writing it—at least glimmers of how we might navigate this situation.

How can we leverage the technologies we’re innovating to drive a positive future rather than a blatantly dystopian one?

That is the hardest question. I feel like that's the question of our era. If a technology is not always subjugated to an agenda—a marketing agenda, a sales agenda, and other sorts of agendas—then it can, potentially, become a tool for good. We need AI that doesn't have an agenda except to be useful and helpful and wise and positive for humans—that has some sense of when to step back and enable humans to connect. But this may be a fantasy.

No thing is without poison. The dosage makes it either a poison or a remedy.

On that note, there’s a scene in Hum where one of the daughters is talking to a digital avatar about her day rather than to her parents, suggesting that the AI is a threat to human connection. But at the same time, I think about how the internet allows a person to theoretically connect with far more people than they ever could in person. So one could argue benefits or drawbacks. What do you think?

I'm not a digital native in the way that my own children are and the way the younger generation is, so I admit that there may be things I don't know. But my instinct is that [AI] is not great [for human connection]. I read a really interesting book when I was writing: Sherry Turkel's Reclaiming Conversation. She writes a lot about this and comments on the incredible ease with which we attribute empathy to robots. If someone—even a robot—is speaking to us in a kind way, if they have eyes and are making eye contact, we basically don't differentiate between that and a human. But it isn't another human, and it won't offer the same kind of friction that we get from human relationships. It won't offer the same kind of texture and complexity. And I think that navigating that when you're talking deeply with someone, and they bring their own life experience to bear, or they have a different perspective on things, or they disagree with you about something—yes, those can be uncomfortable conversations, but they're also how you gain depth.

What kind of research did you do for the book?

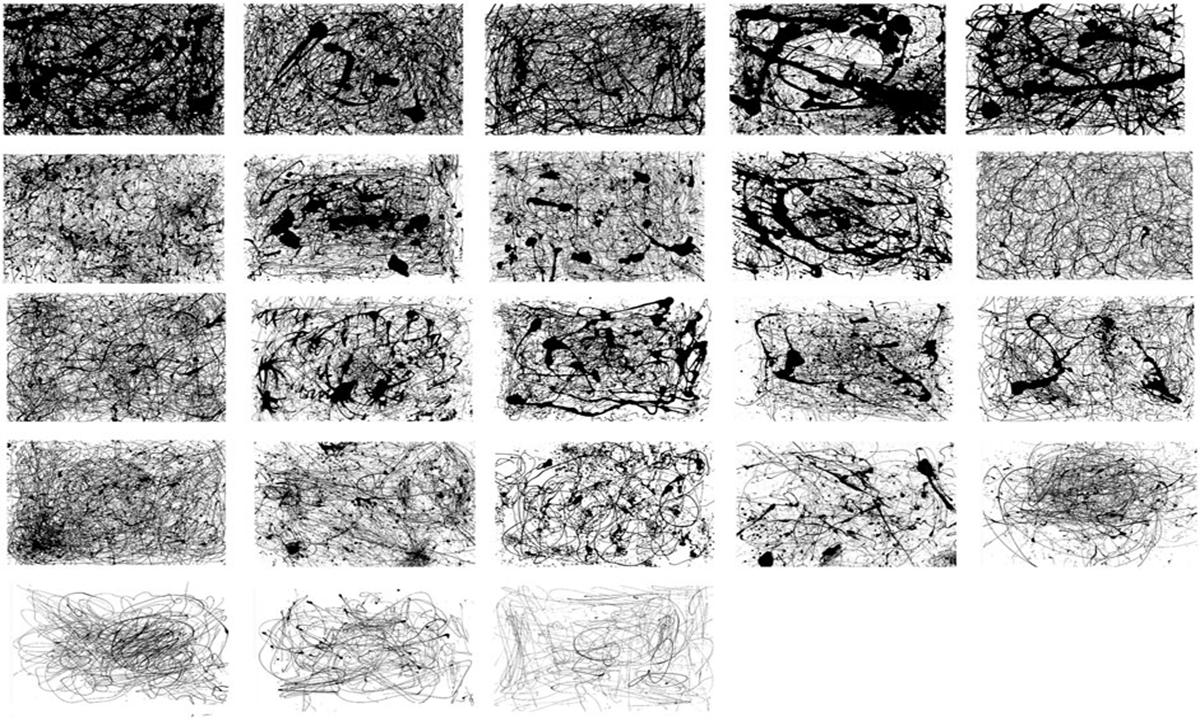

I've never done this before, but at the end I have a long section of notes and a bibliography, and that's a way of sharing with the reader what I was reading at the time. I was reading books about artificial intelligence and reading about climate change. I read The Uninhabitable Earth by David Wallace Wells. And one book that I read early in the process that was quite interesting is called The Artist and the Machine by Arthur I. Miller. It takes a quite positive view of human and AI collaborations in the realm of art and music, so that was an interesting starting place to not be just like, “The robots are going to kill us all.” But rather to ask, “What are positive forms of collaboration we might have?”

Do you think we should fear AI and what the future brings with AI?

Yes, I do think we should fear it. I think we should fear it very much, and I think we should be having a lot of conversations as a society about what kind of world we want to create.

Would you say that you have more reasons for optimism or for pessimism?

I think optimism is important to even the possibility of having a good outcome. Believing that there are meaningful things we can do—even if that's not always entirely true—is important to make us try to do those things. But I have a braided feeling of optimism and pessimism.

Do you have any guidance for young people heading into the uncertain future?

I think that one thing I try to pass on to my children is the feeling of connecting with other people, and how good it is to just sit around a table without your phones just talking and laughing. It's such a simple thing.

I would also mention the epigraph for the book—Poison isn't everything, and no thing is without poison. The dosage makes it either a poison or a remedy—which is from Paracelsus, who was a physician in the 1500s. How do we get the dosage right so that we can reap the benefits without too many costs? ![]()

Lead image: TheRightFrameMedia / Shutterstock