John Jay Hopkins’s visit to Japan in 1955, as an informal emissary of “Atoms for Peace,” must have seemed surreal to everyone involved. Hopkins was the head of an old American shipbuilding firm based out of Groton, Connecticut. Electric Boat Company had struggled in the 1920s and 1930s with its reputation as a “merchant of death,” having sold warships to all sides in major wars. During World War II, it had stuck to the Allied war effort, producing several hundred patrol torpedo boats that became decisive in the island-hopping campaigns in the Pacific between American and Japanese forces. The Japanese had called them “devil boats,” harassing Japanese ships and helping American marines to take control of the vast Japanese Pacific empire. The company had also produced dozens of submarines that killed Japanese sailors. One of these, the USS Barb, was alone credited with sinking 17 Japanese vessels, including the aircraft carrier Un’yō. The Barb even had pioneered the use of submarine-launched rockets, bombarding civilians in towns on Japan’s home islands in 1945.

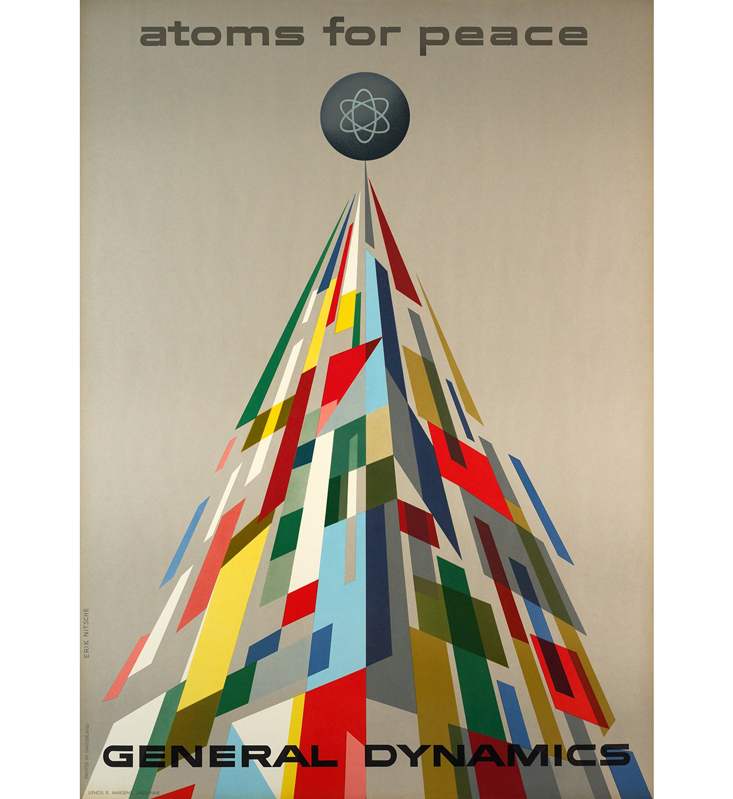

Just 10 years after Japan’s defeat, and only three years after the departure of United States occupation forces, Hopkins was in Japan being treated not as a foe but as a hero. He had made some changes to his company, including its name. It was now called General Dynamics, with Electric Boat one of its subsidiaries, mostly hidden from view. He had hired a graphic designer to help him to rebrand, creating a series of posters with the words “Atoms for Peace” next to “General Dynamics” in several different languages. He made speeches suggesting that American technology was going to provide power and food to the world and that his company stood ready to participate in a kind of global Marshall Plan that harnessed the atom. Perhaps surprisingly, the first country to take him seriously was Japan, the only country to have been attacked with atomic bombs. Hopkins was capitalizing on President Eisenhower’s 1953 “Atoms for Peace” speech, in which he declared the U.S. would use atomic energy “for the benefit of all mankind.”

The event was pure pageantry, with women in geisha costumes, and a thousand Japanese employees chanting “Banzai!”

Hopkins was surprised to be invited there by rich newspaper magnate Matsutarō Shōriki, and after his arrival his astonishment only escalated. He was treated as a celebrity and dignitary, more like a head of state than the head of an infamous defense contracting company. His visit was heralded in local newspapers as the dawn of the new era in the nation’s history. There were lectures and presentations about science, and there was entertainment galore, “on a scale lavish even by Japanese standards,” one CIA document put it. The event was pure pageantry, with women in geisha costumes, and a thousand of Shōriki’s employees chanting “Banzai!” in his honor.

Although the promise of the peaceful atom has been imagined as a successful vision in the 1950s, only to be complicated by nuclear weapons proliferation and environmental concerns in subsequent decades, in reality “Atoms for Peace” opened a Pandora’s Box right from the start. The speech itself was part of a concerted American propaganda campaign, and in some ways it worked like magic, providing the U.S. with a positive agenda at a time when genuine disarmament simply was not happening. It was launched cynically as a propaganda strategy, without a genuine peaceful program in place, and was nurtured with considerable publicity—including working with cartoon filmmaker Walt Disney to turn the atom into a “friend.” The U.S. government eagerly sought success stories that showed the atom as a pathway to abundance and health, but it would struggle in the years to come to offer genuine solutions to developing countries.

The Americans were not the only ones capable of embracing a cornucopian vision of the atom. Eisenhower’s initiative provided rhetorical tools to others who pursued political or even personal goals in their own countries. The first major efforts to take “Atoms for Peace” seriously were in East Asia, particularly post-occupation Japan and South Korea, freshly emerging from the Korean War. In both cases the U.S. would be confronted with its own empty promises because these countries explicitly asked for American help to build nuclear reactors to power their economic resurgence. Instead, U.S. officials stalled for time and wavered, unsure how—or if—they should genuinely encourage a peaceful nuclear industry outside the U.S. and Europe. Japan’s was a particularly striking case, because of the sharp shift in attitudes about peaceful atomic energy—moving from deep skepticism in the late 1940s, to outrage at American weapons testing in mid-1954, to a rapid about-face that favored peaceful atomic energy, mid-decade. The apparent reversal surprised everyone, and soon American officials took credit for it as a propaganda win. Yet it also revealed troubling uncertainties about peaceful nuclear technologies, as U.S. government officials realized they were unable to control the pace and direction of Japan’s nuclear ambitions.

Because the U.S. president’s atomic proposal of late 1953 was conceptualized within a psychological warfare framework, the administration worked closely with newspapers to shape public discussion—starting within the U.S. The president counted on political allies in the press, such as William Laurence of The New York Times. Laurence was long accustomed to helping “sell the bomb,” as one scholar put it, having been paid by both the newspaper and the U.S. government to report in precisely the way government officials wanted, adding his own insights and vivid writing style. His eyewitness account of the bombing of Nagasaki and subsequent essays on the meaning of atomic energy had won him the 1946 Pulitzer Prize for reporting. After the war, “Atomic Bill” Laurence played a crucial role in framing public attitudes about atomic bombings and about the Bikini bombs, and he was tapped to do the same for “Atoms for Peace.” News articles bearing Laurence’s byline, while not exactly as “official” as press releases, were reflections of what U.S. officials hoped to convey to the public, in the guise of detached reporting.

Eisenhower counted on political allies in the press, such as William Laurence of The New York Times, who was accustomed to helping “sell the bomb.”

Together with the newspaper’s longtime science editor, Waldemar Kaempffert, Laurence launched a publicity campaign on the pages of The New York Times focusing on the wonder of the atom, the importance of private enterprise, and the peace-loving attitudes of the president. Just after the new year, Laurence penned “Atomic Power Being Tamed to Turn Industry’s Wheels,” looking back at 1953 as the year marking a transition from military to peaceful atomic energy, as if that had been the intent all along. He expected the coming decade to bring “epoch-making progress” to detect and treat diseases and to put the atom to use “in a thousand and one fields of endeavor, as widely divergent as are archaeology and agriculture.” He predicted that all the heretofore-unheralded applications might turn out as “tails wagging the atomic dog.”

Laurence’s predictions included the so-called breeder reactor, which would be able to use by-products of fission as fuel, allowing humans “to multiply nature’s niggardly store of atomic fuels by a factor of 140, or about 14,000 per cent.” That was 23 times what was produced by all conventional fuels combined, he enthused. The article led with an image of the naval submarine USS Nautilus at the center—labeled “power”— surrounded by other images representing oil research, new metals, chemicals and medicine, and plants and foods. The latter was one of Brookhaven’s gamma gardens.

Laurence made the world seem wide open to fantastic possibility, and he hewed closely to the administration’s line that peaceful uses of atomic energy were themselves a form of arms control. He spoke of the “transition” from military to peaceful uses as if playing a zero-sum game with the world’s supply of uranium. The more it was used for peace, the less it would be used for war. He also reported on the first “atomic battery” made by RCA, using strontium-90. It was initially employed by the company’s chairman of the board David Sarnoff to send a message via telegraph: “Atoms for peace. Man is still the greatest miracle and the greatest problem on this earth.” Laurence heralded it as an important new source of electricity, and he believed strontium-90 would be widely available, cheap, and destined to “find thousands of potential uses in the developments of atomic energy for the peaceful pursuits of mankind the world over.”

Major publishing houses helped promote the government initiative as well. Random House’s series on science, “All About Books” included a volume on atomic energy, eventually published in 1955. Written by Rutgers University professor Ira M. Freeman, All about the Atom contained all of the optimism found in the president’s program, especially for the poorest countries of the world. “The United States and other countries could lend nuclear materials and engineering help to the undeveloped regions of Asia and Africa,” he wrote. “This would make the neglected parts of the world flourish. In just a few years, they could make more progress than in many centuries before.”

Although Eisenhower did not use the term “Atoms for Peace” in his original speech, newspapers picked it up immediately. It was an old term—already employed from time to time, such as when discussing nuclear-powered electricity. Going forward it would be linked unmistakably to this particular speech and plan by Eisenhower. Other phrases would soon be added, notably “plowshare.” It was a reference to the prophet Isaiah, whose memorable words from the Bible referred to soldiers beating their swords into plowshares, turning weapons of war into farm implements.

For Walt Disney, this “public service” was a collaboration that would draw potential visitors to his new theme park.

One corporate ally who immediately latched onto the president’s speech was Hopkins. One of the General Dynamics’ biggest government contracts was the USS Nautilus, a submarine built for war, powered by an atomic reactor, and named after the submersible craft in Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. The work on the ship was begun during the Truman administration, but the Nautilus’s launch occurred on Jan. 21, 1954, less than two months after Eisenhower’s historic speech. Hopkins spun the launch of the Nautilus less as a victory for the U.S. Navy and more as a step forward for humanity. One company-produced brochure about the launch noted, “The ‘Nautilus’ will be listed in the annals of man as the first demonstration of his ability to curb the destructive force of the atom and to turn it in positive directions.” Gwilym Price, the president of Westinghouse (which manufactured the reactor itself), observed that the Nautilus was “a testimonial to the ability and determination of free men to act in the defense of human rights and dignity.” The navy had a new class of submarine that could stay submerged for extended periods without the need for refueling, but those at the christening ceremony described it as a boon to humanity and a part of the new peaceful direction of the atom.

Hopkins saw the opportunity of using “Atoms for Peace” to consolidate the rebranding of General Dynamics as a purveyor of technologies beyond the conventional wartime domains of Electric Boat. He dreamed of atomic ships and airplanes and eventually would create a subsidiary— General Atomics—to sell research reactors to countries around the world. He had his sights set on August 1955, when the Eisenhower administration planned to sponsor a major international conference on the peaceful atom in Geneva, Switzerland. There would be opportunities for contractors to put up exhibits, and among these contractors were American household names like General Electric, Westinghouse, and Union Carbide. Hopkins was determined to seize the opportunity to mark his newly named company as modern, progressive, and futuristic.

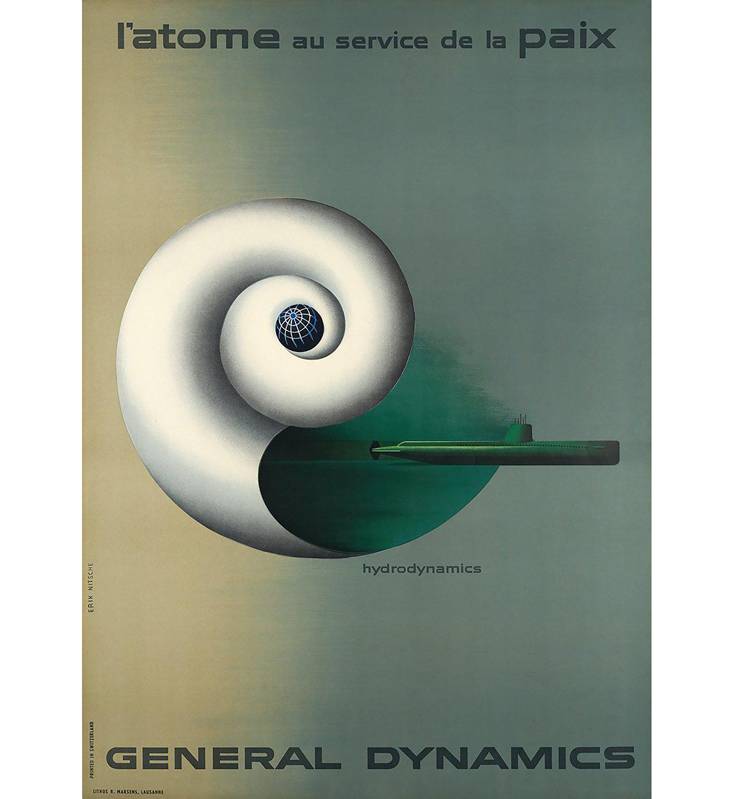

His primary publicity instrument was the Swiss-born graphic designer Erik Nitsche, whose style fit this vision. Nitsche’s work for General Dynamics would mark him as one of the most influential modernist graphic designers. His drawings were suggestive of a scientific mindset, with an aesthetic sensibility that blended imagination with clarity and orderliness. Simple yet elegant, with precise shapes and lines but abstract in concept, his artistic renderings were the perfect fit for the relatively unknown future of atomic energy. As one writer later wrote, “Nitsche’s brand of artful futurism was copied by many others at the time and might be seen today as representative of the so-called ‘Atomic Style’ that emerged in the mid- to late-1950s.” He made six posters for Hopkins for the 1955 conference, each featuring the firm’s name along with the phrase “Atoms for Peace” in one language or another. The French one featured the word “hydrodynamics” along with a visual of the Nautilus, positioned not as a war vessel but as a harbinger of peace. The German one, on “aerodynamics,” showed the atomic-powered airplane then under development. There was a Japanese one too, on “nucleodynamics,” and it was highly abstract—a series of colored squares (some have described it as a rendering of isotopes), with an inset photograph of two physicians.

There was no better friend to the atom, however, than cartoonist and film producer Walt Disney, who agreed to promote the peaceful atom with a new film to be aired on television. Disney producers later explained to the FBI that it took about a year and a half to prepare for it and to film it. “This type of film is usually not profitable for the company; however, Mr. Disney likes to do films of this type occasionally as a public service.” Disney was already a household name for inventing Mickey Mouse in 1928 and making the 1937 blockbuster Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. In early 1954, when “Atoms for Peace” needed some publicity, Disney was coming off the success of Peter Pan (1953) and was in the process of planning an ambitious theme park, to be built in Anaheim, California. He also had partnered with the American Broadcasting Company to produce a series of television programs for children. All of this put him in an important position to influence young families’ attitudes about all manner of things, including atomic energy. The FBI’s 1954 assessment of Disney was that he was reliable, cooperative, and “extremely prominent in the motion picture industry,” and that year he became an approved FBI contact for the bureau’s “Special Agent in Charge” in Los Angeles.

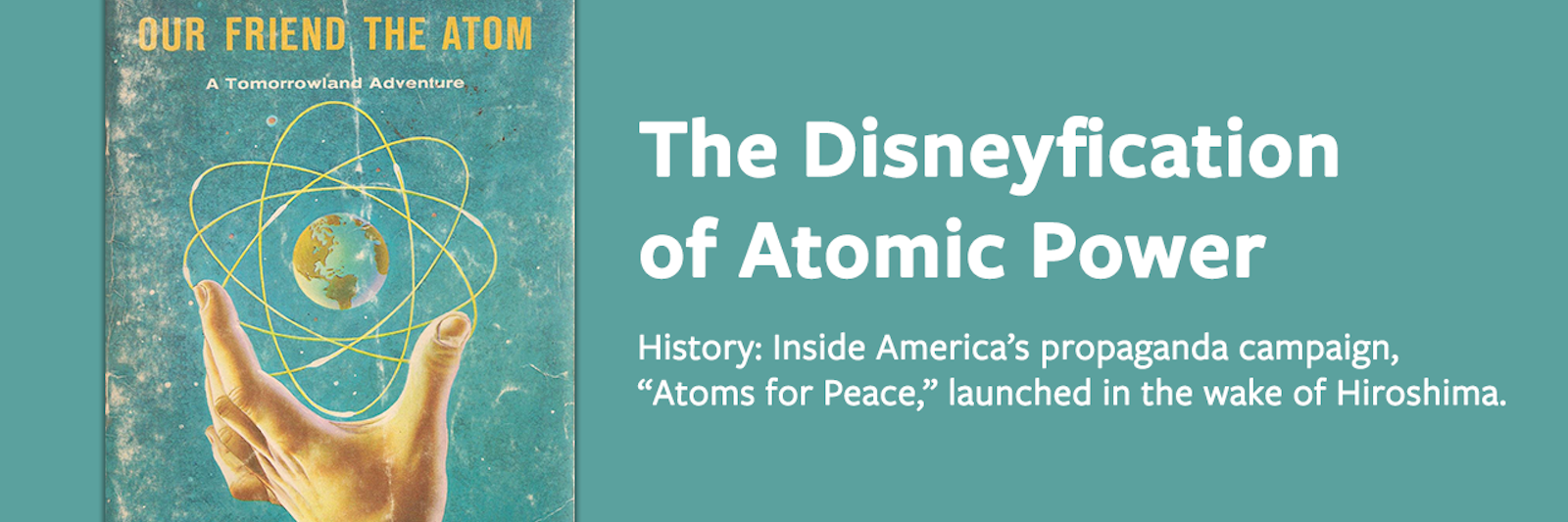

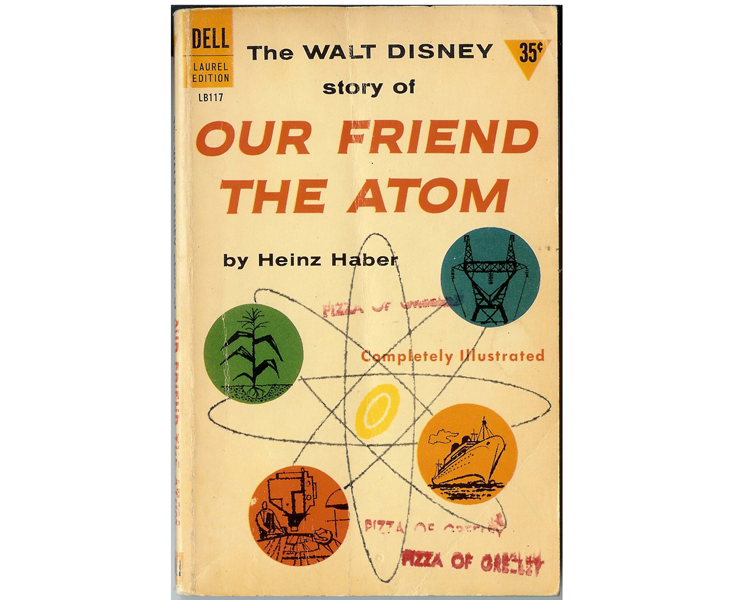

Disney’s production, Our Friend the Atom, borrowed ideas already established by General Dynamics. On screen, Disney himself provides some introductory remarks while standing in front of several of the Nitsche posters. He makes a reference to Jules Verne’s 1870 Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. “Fiction often has a way of becoming fact,” he says, holding up the Verne book. Then he moves over to two scale models of submarines, one styled after the one in the story and another a replica of the “real” Nautilus—the USS Nautilus, the first ship to be powered by a nuclear reactor. He does not mention that it is a war vessel. “It’s the first example of the useful power of the atom that will drive the machines of our atomic age,” Disney states, adding, “The atom is our future.” He then goes on to describe the many atomic projects that the Disney studio is planning in addition to the television program, including a book and ambitious exhibits as part of the Tomorrowland portion of the amusement park in southern California.

For Disney, this “public service” was a collaboration that would draw potential visitors to his new theme park. For his program on the atom, he drew from the same network of scientists he was already using to make a similar television program on space exploration. As narrator he chose Heinz Haber, whose gentle demeanor, foreign accent, and silvery hair lent the discussion some scientific gravitas. He was not a nuclear physicist, though. In the previous decade, Haber had been working as a rocket scientist in Nazi Germany and was likely introduced to Disney producers by fellow rocket specialist Werner von Braun. Both von Braun and Haber had been captured toward the end of the war by Americans under Operation Paperclip and went to work for the U.S. Army. Together with another colleague, Willy Ley, the two had written a series of essays on space exploration in Collier’s magazine. These had captured the attention of executives at Disney, who saw space as the perfect subject for Tomorrowland. Producing educational television programs about space exploration seemed like a great advertising opportunity for the new theme park. Kimball reached out to von Braun and soon both he and Haber became technical consultants for Disney. The first of the space programs aired on ABC on March 9, 1955. Von Braun focused on space, while Haber became the face of Disney’s atom.

The Disney version channeled U.S. policy perfectly, with the book and television program both titled Our Friend the Atom. In the 1957 program, Haber eases into the discussion by saying that, yes, it was a science story, but that “it was almost like a fairytale. By a strange coincidence, our story turned out to be like the old fable from the Arabian Nights, ‘The Fisherman and the Genie.’” Rather than discuss technical details, Haber begins by telling the story of a fisherman attempting to convince a magical creature, living in an ancient-looking container pulled from the sea, to do his bidding. Cartoons, orchestral music, and voice actors play out the story, before Haber reappears on screen to say that “we are like the fisherman. For centuries, we have been casting our net in the sea of the great unknown in search of knowledge. And finally,” he says, holding up a rock, “we found a vessel. And like the one in the fable, it contains a genie. A genie hidden in the atoms of this metal, uranium.” The cartoon genie then shows that it is radioactive by holding a Geiger counter next to it and drives the theme home: the genie is liberated, it first threatens to kill, and then it is “finally harnessed to grant us three wishes.”

The publicity campaign for the television program and book was enormous. It involved syndicated news stories, magazine features, brochures, and even a school donation program calling on businesses to buy prints of the film to distribute in schools. The brochure for the donation program stated that “at the threshold of the atomic age we find our nation critically short of trained scientists and engineers so necessary if we are to reap the many benefits the friendly atom can bestow upon us.” Of course, all of the cross-promotion was tied to Tomorrowland at Disneyland.

The television program proposed the atom not merely as a “friend,” to be juxtaposed with the warlike atomic bomb, but also as a solution to a serious problem confronting the world—the limitations of nature. Haber notes that “the coal and oil resources of our planet are dwindling” and calls upon the genie to provide power. He also notes that humans continue to suffer from hunger and disease and says that our second wish for the genie should be “food and health.” Finally the last wish is peace—to let the genie be a friend forever.

Jacob Darwin Hamblin is the author, most recently of The Wretched Atom: America’s Global Gamble with Peaceful Nuclear Technology. He is an American historian who is a professor at Oregon State University. He writes and speaks about international dimensions of science, technology, and the environment, especially related to nuclear issues, ecology, oceans, and climate.

From The Wretched Atom: America’s Global Gamble with Peaceful Nuclear Technology by Jacob Darwin Hamblin. Copyright 2021 by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

This article was originally published on our Spark of Science Channel in October 2021.