As little as two centuries ago, the northern edge of the island of Borneo, home to Malaysia’s Sarawak state, was covered in a verdant canopy that stretched, uninterrupted, from shore to shore. It was a forest that had persisted for more than 100 million years, sheltering a dizzying abundance of plants, animals, and fungi that were found nowhere else on Earth. It survived the extinction of the dinosaurs and countless cycles of glaciation. It housed humans for 40,000 years while our species grew and grew around the world.

Then, over the past few decades, the forests of Sarawak faced threats unlike any before. The canopy began to recoil, its edges assaulted by the expansion of hydroelectric power, logging, and, most impactful of all, palm oil plantations. To many people, these changes look like the necessary costs of progress. Development has consumed almost a third of the forest, but it has also lifted millions out of poverty. The first wave of palm oil plantations, from the 1970s to the 1990s, provided farmers with seven times the income of subsistence-food croppers in the same regions. Industry has brought paved roads, better schools, and modern information infrastructure.

The oil palm is a Shiva of the modern consumer economy, a great creator and a great destroyer.

The oil palm (formally Elaeis guineensis) is a Shiva of the modern consumer economy, a great creator and a great destroyer. A startling amount of human happiness and wellbeing depends on our relationship with this one plant. Presently palm oil accounts for 60 percent of all cooking oil, more than 62 million tons in total. It’s found in half of supermarket goods, from instant noodles to ice cream, air fresheners to shampoos. You may not see it but you are eating it and washing your hair with it. Consumer-product manufacturers prefer palm oil because it blends well with other oils and is the ideal elixir to create various consistencies. Savvy food marketers love it because it contains low levels of artery-clogging trans fats.

You’d have to look far and wide to find a major company that doesn’t have palm oil on its hands. They include Walmart, Colgate-Palmolive, Kellogg’s, Nestle, McDonalds, Ikea, Target, and Whole Foods. Palm oil is mixed into animal feed and biofuels.

Malaysia accounts for 26 percent of the vast production of palm oil today, making it a great creator for the local economy as well. Almost half of oil palms in that country are grown by smallholders rather than large-scale agribusiness. The crop is so important that government insiders consider its development synonymous with the eradication of poverty in Malaysia. Between 1980 and 2010, palm oil cultivation doubled in Malaysia. Then, in just four years, it doubled again.

Therein lies the seemingly intractable dilemma of humanity’s intimate relationship with this tropical tree. Palm oil production is phenomenally important to local peoples and international economies. But it is also tremendously destructive to natural ecosystems and to the global climate.

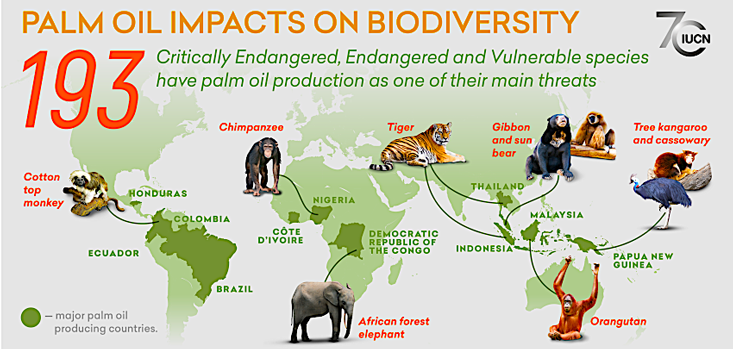

Tropical forests and peatlands are great storehouses of carbon dioxide, the main gas indicted in global warming. Malaysia’s forests are especially rich in carbon. They can hold up to 220 pounds of carbon per square mile. “That’s equivalent to the emissions from driving an average car from New York to San Francisco and back 76 times,” the Union for Concerned Scientists tells us. Razing forests and peatlands unleashes carbon dioxide into the atmosphere in calamitous amounts. Deforestation for palm cultivation in Indonesia accounted for 2 to 9 percent of all tropical land use emissions from 2000 to 2010. Palm oil expansion is also robbing orangutans, tigers, rhinos, and elephants of their natural habitats. Global demand for palm oil is expected to increase from 76 million tons in 2019 to over 400 million tons in 2050.

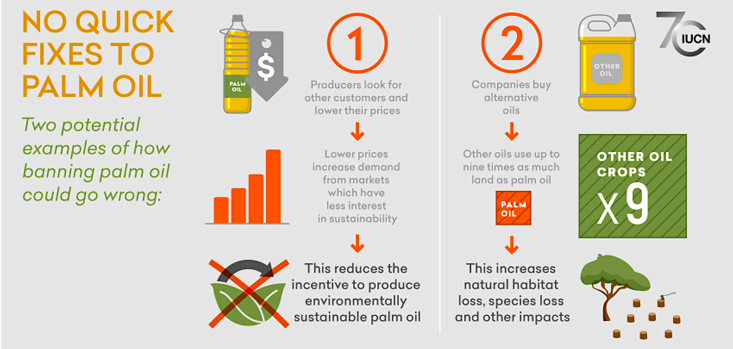

Environmentalists are realists enough to know that palm oil is here to stay. Too much money and too many powerful government and community interests are tied up in its production. You don’t overturn the world economy overnight. Plenty of nonprofits are pushing sustainable harvesting of palm oil and an international movement, Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, is signing up companies to pledge to employ smart environmental practices. These grassroots efforts, though important, may amount to little more than a superficial solution, however.

What’s most needed is way to reboot our relationship with the oil palm—to find a way to produce more oil on less land. Here is where plant scientists must step in. And they have. They have crafted a novel genetic technique to induce each palm oil tree to produce more fruit, containing more of the precious oil. It’s a way to keep the ice-cream makers happy while saving the rainforest, and it can be scaled up now.

Rob Martienssen, a plant biologist at Cold Spring Harbor Lab, has been one of the world’s key researchers into the puzzles of palm oil production: why scientific methods have gone wrong in the past, and how to right those wrongs today. Launching a project to grow more palm oil on less land was the easy part, he knew. Scientists locked in on that goal some decades ago and set out to clone a single “elite” palm, one that produced a bounty of oil, into 50,000 palms just like it. They even succeeded, up to a point. “They thought this was going to solve all problems,” Martienssen says, but cloning the elite palm in the lab turned out to offend the plant’s natural growth processes. Once planted, the identical trees were “mantled”: Instead of yielding the promised bounty, the plants produced gnarled fruit that gave no oil.

It took an international collaboration between Martienssen’s group at Cold Spring Harbor Lab and their colleagues at the Malaysian Palm Oil Board nearly 20 years to unravel the mystery of the mantled fruit. They started by assembling and analyzing the whole genome sequence of the Elaeis guineensis oil palm. That enormous effort only made the problem more puzzling, however, because they found no genetic differences between normal and mantled clones.

Rather than give up, the researchers dove even deeper, beyond the DNA of the oil palm and into the layer of biology that regulates how DNA is read and translated: the epigenome. To their astonishment, they found that the huge difference in the mantled clones was the result of a single, tiny epigenetic change. Palms that produce mangled fruit have an altered molecular switch that interferes with expression levels of genes relevant to healthy fruit production. Previously that miscreant switch had been identified in rice plants and was named “karma.” The palm clones literally suffered from bad karma.

“In terms of individual palms, if you have bad karma, then it’s going to literally get no oil,” Martienssen says. With the mechanism behind mantling unmasked, a third partner—Orion Genomics, a private startup founded by Martienssen—was able to develop a simple DNA test that predicts whether a designer seedling will bear robust or withered fruit. Then only the genuine, high-yield clones will make their way into the field.

That epigenetic test could be making a difference in the oil-palm plantations very soon. “It’s currently being commercialized jointly by the Malaysian Palm Oil Board and Orion Genomics,” Martienssen says. He projects that reliable clonal stocks could increase yields by 30 to 50 percent, drastically reducing the pressure for illegal forest clearing. And that’s just the start. Other scientists are working on dwarf varieties of the oil palm that are easier to harvest, that come to maturity faster, and that stay in production for longer. The epigenetic test can be applied to genetically modified palm varieties for a synergistic effect, but—important for many consumers and environmentalists—it provides major benefits on the non-GMO clones as well.

In Malaysia, the government is finally acting to protect what’s left of Sarawak’s ancient forest canopy. New policies limit the expansion of palm plantations to 6.5 million hectares, which leaves just 1 million more hectares of land for cultivation. These moves create strong incentives to enact a better, smarter relationship between humans and the plants they rely on. “From a world production point of view, palm oil is not going away,” Martienssen says. “Reducing its footprint is the best thing we can do to help the rainforest.”

Anastasia Bendebury and Michael Shilo DeLay are biologists and co-creators of the science blog, Demystifying Science. Follow them on Twitter @Demystifysci.

Lead image: A palm oil plantation and mill in Sabah, Malaysia. By CEPhoto/Uwe Aranas.

This article was originally published on our Biology and Beyond channel in June 2020.