So I’m reading The Fly Trap by Fredrik Sjöberg, a slim book by a writer I’ve never heard of, and I’m riveted for reasons I can’t explain. I honestly have no idea what the book is about. The author begins by talking about the time he worked as a prop man for a Swedish stage production of Sam Shepard’s Curse of Starving Class, amazed that one of the actors could urinate on stage every night on command, as the script calls for.

The author moves to a tiny Swedish island and learns his real talents lay with collecting flies that hover around flowers. “That’s a fate that takes some getting used to,” he admits. He says he’s an entomologist but really more of a writer, although he’s not entirely sure what his story is about. “Some days I tell myself that my mission is to say something about the art and sometimes the bliss of limitation. And the legibility of the landscape.”

Then he goes into a rhapsodic passage about a Finnish entomologist who investigated insect wing frequencies. I learn a “pooter” is a plastic tube that collectors use to suck hovering flies out of the air. Soon he runs into a British botanist on the island, called Runmaro, who strangely tells him, “I’m looking for you,” though he learns he was actually saying, “I’m looking for yew,” trees that grow abundantly on the island.

So as I read with pleasure, laughing at his deadpan sarcasm about tourists, learning about hoverflies, marveling at his apercus about the narcissism of collectors and the misunderstood meaning of slowness, I put down the book and asked myself out loud, “Who is this guy?”

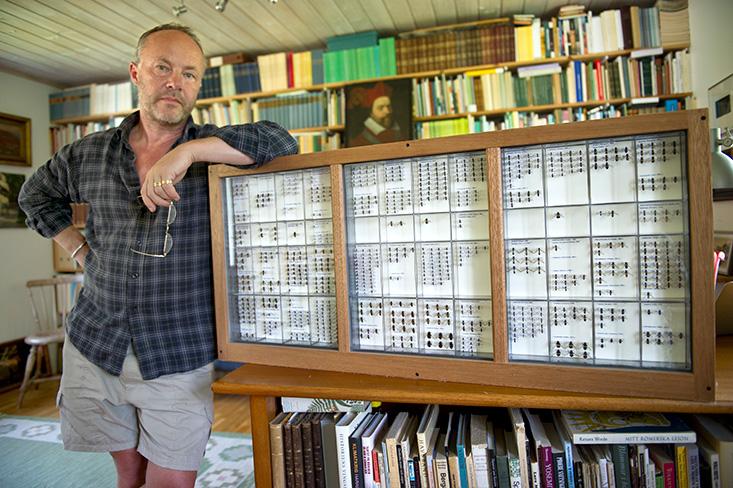

Sjöberg, 56, is in fact a well-regarded writer in Sweden. He made his name in Swedish newspapers and magazines, writing about the environment, science, and local culture. Having published a few popular science books that were not very popular, he got the wild idea to write a “sort of memoir” about his life on Runmaro, where he and his wife Johanna, who raised three daughters, have lived now for 30 years. Published in 2004, and to the surprise of Sjöberg and his agent, the unclassifiable The Fly Trap became a sleeper hit in Sweden, selling 30,000 copies. Translated into nine languages and finally into English, it will be released in the United States in June.

To our delight at Nautilus, an excerpt from The Fly Trap is making its U.S. debut on our pages today. It’s the inaugural new story in Nautilus Prime, our subscription series that includes access to bonus articles, tablet editions of our award-winning print magazine, and eBooks of every online issue we’ve done.

Excited and curious to learn more about the original voice of The Fly Trap, I recently called Sjöberg. He was stationed at an apartment he keeps in Stockholm, where he often writes. In conversation he was as engaging as funny and full of insights as he is in The Fly Trap.

How long did you work on The Fly Trap?

I wrote it pretty quickly, in 100 days. I had the idea for a couple of years that I wanted to write about limitations—although the book is not very limited, it’s almost about everything! It was also the first book I wrote in Stockholm. I wanted to be somewhere else than the island, and so I deserted my family and worked very hard seven days a week for 100 days.

Why did you want to write about limitations?

You meet a lot of people who love living on islands, and even more people who hate islands. They feel like they’re in a trap. I love living on an island and I started to wonder why that is. When was I young I realized that when time is limited, you always fall in love. I had this conversation with a young woman from Chile in the Los Angeles airport. We had just met and we knew from the beginning that we had 10 hours or something like that, and we will never meet again. This was a magical moment, and this is another kind of limitation that I wanted to explore. So it’s geographical limits, it’s limits in time. And collecting flies made me happy. I was in my 40s and I was thinking of what to do with the rest of my life. Some people buy a boat and sail around the world. I could’ve started playing golf or drinking alcohol. But I collected flies.

When did you start collecting them?

You could say it began 2001 with a friend of mine, the poet Tomas Tranströmer, who got the Nobel Prize several years ago. I knew him from the island because he was brought up on Runmaro and he collected insects when he was young. When he was 70, I wrote a little book about his insect collection. Then I started to write about insects myself. But because I knew almost no one is interested in insects, I had to tell stories about other things, mainly people, scientists, artists, and other lunatics.

Do you have a degree in science?

Actually, no. I have two honorary doctorates; I’m very proud of that. This is now my new topic of collection—I collect honorary doctorates! Please write that, because I want more! But no, I don’t have a Ph.D. in biology because I quit before that. I started to write instead. I had studied biology for quite a few years, I knew a lot about that, and also I had been dealing with biologists since I was a kid because I collected beetles, butterflies, and stuff like that.

Were your parents scientists?

No, not at all. My father was an engineer and a photographer. My mother worked in a kindergarten. I was brought up in a small town in the south of Sweden, half nature, half urban. I think that’s why I’m always in between nature and culture, on the border between. And writers, you know, most of us are a bit narcissistic; we want to be masters of the universe! And to be a master of the universe in beetle collecting you need to spend the whole of your life and even then you cannot be sure to be the best one. But almost no one collected these kinds of flies, so I became an expert pretty fast.

Describe the island of Runmaro for us.

It’s 15 square kilometers and has nine lakes. I live on the shore of one of the lakes. There are 700 species of flowering plants. I think there are something like 250 to 300 inhabitants all year round, and about 4,000 in the summer. It’s very forested, but in the old days it was deforested because of mining businesses and peasants were living there. Not anymore. Nowadays it’s rich people from Stockholm—and me!

Why did you move there?

When I was 25, I moved to Stockholm to work in the theater and to make a career of some kind. After a couple of years, I met my wife and she very quickly got pregnant, and we needed someplace to live. Back then in the ’80s, it was already expensive to buy an apartment in Stockholm. But on the islands you could still find old shacks pretty cheap. We bought an old house built around 1890. It was 60 square meters. My wife is a bookbinder and she had her things stuffed in a corner. The house was heated with firewood in a kitchen stove. We didn’t have running water for the first 10 years. We had a well on the ground with a pump, so I went there with two buckets every day to get the water. We had three kids, who lived in a small room, and they were bathing on the floor in the kitchen—which was misery! We were young and stupid. And that was our luck.

What attracted you to hoverflies?

Well, they are beautiful. But that’s not the main reason. They are very diverse when it comes to their ecology. When you recognize a species, you can tell a lot about the quality of the nature. Hoverflies are connected to very old, hollow oak trees, for example. Since I was young, I was very interested in biodiversity. Actually, 20 years ago, I translated to Swedish Edward O. Wilson’s The Diversity of Life. When I was young and into the environmental movement, biodiversity was my thing. The flies, well, they were just a way of reading the landscape. You can read the landscape as a birdwatcher or as a botanist, but the flies were my way of reading it.

Describe the mind of a collector.

The collector is a special kind of man, and it’s often a man, because it’s about control over something. We’re living in a world without borders, information is accessible everywhere, and it’s easy if you were brought up in Sweden to get anything you want. Then you need to be the master of something. Collecting flies is perfect because you need to be very concentrated when you try to catch hoverflies. And it’s also very cheap compared to drinking!

Did you think The Fly Trap would sell well?

Oh, no, I thought it might sell a couple thousand copies. I didn’t even imagine I would get an audience overseas or in any other country. I was ambitious. My main goal in life then and now is to make an impression on women! When I was 25, I tried to write novels. They were, well, terrible things; happily I never tried to publish them. So of course I had literary ambition. I didn’t want to be a biologist. How boring is that? I wanted to be a writer on the scene. When The Fly Trap first came out, the literary critics tried to determine, “What is this?” I got that question all the time. Then I started to think that, Well, maybe this is a memoir. So that’s what I call it nowadays.

The Fly Trap is the first of three books written in a similar vein. The others are out in Sweden and in coming years will be published in Europe and the U.S. Has anybody, given the international acclaim for My Struggle, the series of novels written by Norway’s Karl Ove Knausgaard, based on his personal life, called you the Knausgaard of the Swedish isles?

I’ve been called a lot over the years, but as far as I know never an insular Knausgaard. You may call me anything, but I’d rather not “Lord of the Flies.”