If there is one thing that the coronavirus pandemic has exposed, it is that there is much that we still don’t know about the world around us. Forget about the trillions—OK, more than trillions—of galaxies in the universe that we’ll never explore. Just at our feet or in the air around us are cohabitants of our own world, some alive, and some—viruses—that occupy an odd liminal space, not quite alive, but not dead either. They exist in what is effectively a hidden world, almost a “first Earth” that is both just off-stage and right in front of us, and even inside of us. It’s a world teeming with activity, full of blooming, buzzing, confusion, competition, and evolution. Sometimes we explore it intentionally, but at other times we run into it by accident, most noticeably when the alarms on one of the megafauna bio-detectors—people and animals—go off. It’s when these encounters happen that we remember that the space of things that we don’t know is truly unfathomable.

Puttering around on the edge of the known and the unknown is the standard work of science and scientists. While the twinkling of the night sky may often be an inspiration for meditations on how little we understand, it’s actually what we can’t see in the cosmos that is the best reminder of our limited vision. In 1933, Fritz Zwicky observed a huge discrepancy in the amount of gravitational force needed to account for the rotational movement of galaxies and the amount that could be attributed to the visible matter in the galaxy. Naturally, he called this “dark matter.” In 1980, Vera Rubin and Kent Ford used spectrographic data—its own form of making visible the invisible—to show definitively that galaxies contain at least six times as much dark mass as visible mass. As it turns out, Aristotle was wrong: Nature does love a vacuum—that’s where it stores most of its stuff.

The pandemic has brought us closer than is comfortable to the engines of selection.

Countless studies and observations later point to the conclusion that nearly 30 percent of the universe is made of dark matter. The dark matter is a big part of what holds the universe together—more stuff for creating attractive forces between things. But, as you may know, ever since the Big Bang the universe is actually expanding. The cause of this is a different force of darkness, something that goes by the name dark energy.

Our understanding of the biological world has also been a story of discovery of dark matter and dark energy—our collision with the coronavirus is just a most recent reminder of that theme. Early censuses dramatically underestimated the amount of living matter, darkness of understanding largely borne of poor optics. Our inability to see at the scale of microorganisms was a source of a good deal of pseudoscience bordering on mythology, especially when it came to disease. “Vapors” and humors were the first dark matter. It was only in the 1880s, 20 years or so after the publication of Darwin’s The Origin of Species, that Robert Koch discovered bacteria and in so doing revealed a material cause for infection. Among Koch’s great advances was his use of staining and culturing to make visible the agent of infection. We now know that bacteria and other microorganisms account for most of the world’s genetic diversity, not only in the world at large, but also within our own bodies, where our inner microbial ecosystem of the microbiome turns out to be crucial to human health. Some forms of “infection” are deadly, but some are necessary.

Viruses—like the coronavirus—are even smaller than bacteria and so were also dark for some time. They were also brought to light in the late 19th century, discovered by the Dutch microbiologist Martinus Beijerinck in the course of investigating the etiology of mosaic disease in tobacco plants. Repeated efforts to culture the source of the disease failed, so it wasn’t bacterial in nature—biologists were the first to understand that you need culture to live—but whatever was causing the disease was able to replicate. It was alive in some ways, but dead in others. Beijerinck called this “infectious agent” a virus.

We now know that a virus is basically nano-encapsulated genetic information. They have existed from the beginning of biological time, emergent from the proverbial primordial soup, a string of atoms, clumped into molecules, wrapped in another kind of molecular shell, a kind of biological M&M. The raison d’etre of the virus is reproduction, which ironically leaves a fair amount of death in its wake. But really, the virus is an engine of life whose dynamics and mechanisms of existence and reproduction make it the agent of genetic expansion, a “dark life” biological force to the dark energy physical force fueling universal expansion that is dark energy. Not quite twins separated at birth, but siblings separated by several billion years, give or take.

We live in an invisible ocean of microbial diversity and menace.

As a force for life viruses account for many of evolution’s most exceptional selective pressures and innovations. The early successful viral reproductive process of simple genetic segments inserting themselves into ancient host genomes served as an early stage in the evolution of the “eukaryotic cells” that comprise later larger and more complex single cell and multicellular organisms (us). The “pressure” of the fundamental goal of reproduction has according to many, worked its evolutionary magic at even greater scales. Sure it’s the reason that a virus “learns” how to jump from animals to humans, but it also has been hypothesized that it’s a drive that has fueled the evolution of recombinational sex, the kind that all animals and plants use. So a virus not only engendered multicellular life, it lifted life from the monotony of asexuality.

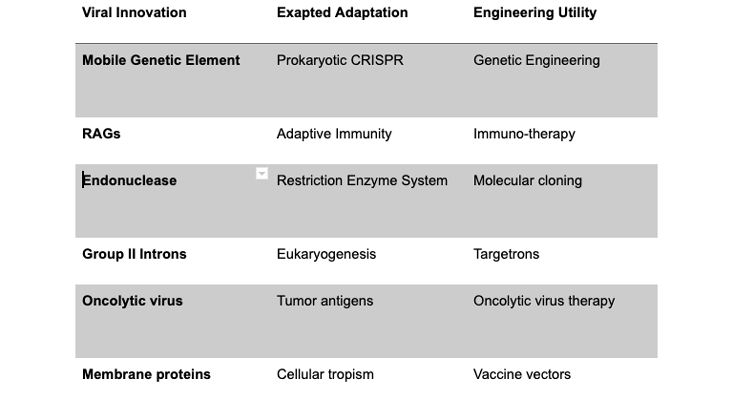

In a kind of Nietzschean “that which does not kill us makes us stronger” way, any ability that we do have to fight off some diseases can also be at least partly attributed to viruses. Without having acquired genes of viral provenance about 500 million years ago, the jawed vertebrates—which includes all vertebrates but lampreys and hagfish—would have no adaptive immune system, without which most vertebrates would have minimal means of fending off viruses. Without immune systems, researchers would have no ability to develop immunotherapy. CRISPR, the most revolutionary genetic engineering tool in the history of biological science, is effectively the recapitulation of our biological antivirus defense system that kills an infiltrating virus by slicing it into genetic pieces. Current vaccine delivery techniques and other forms of biological therapies rely on a mimicking of or instigation of virus insertion mechanisms. What was once dark, was eventually brought to light, and once brought to light, helped to bring light—and life.

Our all too human tendency to focus on what is directly or instrumentally visible, or of comparable scale to ourselves, has blinded us to both the largest and smallest scales of the universe. Scales where physical forces shape the elementary structure of matter. But also blinded us to those living scales invisible to the eye that have shaped the form and function of adaptive matter. The COVID-19 crisis has made the terrifying dark energy of evolution visible and brought us closer than is comfortable to the engines of selection. We live in an invisible ocean of microbial diversity and menace, and one that is insensitive to the transience of multicellular life. Maybe it is a moment for us as a culture to learn from our microbial allies in the universe of dark matter—the bacteria, from whom we acquire our symbiotic microbiome—that the best way to defeat the dark energy of the virus is to turn its entropic ingenuity against itself and out-evolve the virus by evolving our scientific ingenuity and probably our social practices too. We’ll have to adapt—what choice do we have?

David Krakauer is the president and William H Miller Professor of Complex Systems at the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico. He works on the evolution of intelligence and stupidity on Earth. He is the founder of the InterPlanetary Project at SFI and the publisher/editor-in-chief of the SFI Press. His most recent book is an edited volume, Worlds Hidden in Plain Sight.

Dan Rockmore is the associate dean for the sciences and the director of the Neukom Institute for Computational Sciences at Dartmouth College. His most recent book is an edited volume, What are the Arts and Sciences? A Guide for the Curious.

Lead image: agsandrew / Shutterstock